View the original article to see embedded media.

When Jim Bintliff first heard that MLB wanted to standardize instructions for applying mud to its baseballs, two ideas came to mind.

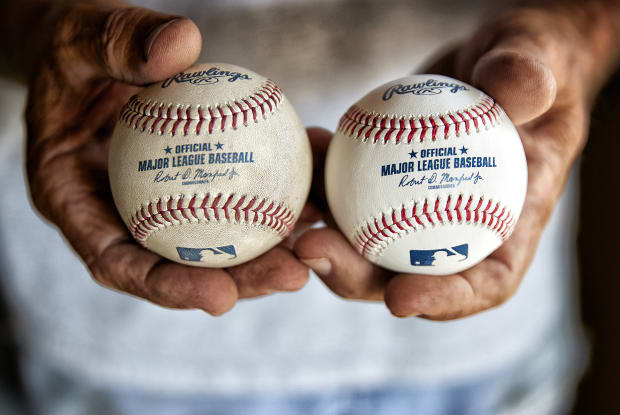

The first was a little sad: He’s always appreciated that some clubhouse attendants have their own styles when it comes to preparing a baseball. These new instructions, Bintliff figured, would do away with those idiosyncrasies for good. Because a brand-new baseball has a shiny, factory gloss that can make it difficult to grip, it needs to be rubbed down before it can be used in a game, and for decades, MLB’s rules have dictated that process involve just one substance—mud. Now, in the interest of consistency, teams have been instructed to make sure their clubbies follow just one set of instructions for the process, too. Scoop two fingertips’ worth of mud. Paint it across the entire surface of the baseball. Rub the ball in between both hands for no more than 40 seconds. The memo MLB sent to clubs this week spells out all these steps and more.

But the second idea was much happier for Bintliff: If they’re giving teams instructions to make sure they’re all applying mud in the same way, he thought, they must not be ready to give me up any time soon.

LEBRECHTMEDIA/Sports Illustrated

The mud in question is not just any mud. It’s Bintliff’s; before it was his, it was his father’s, and before it was his, it was Bintliff’s grandfather’s. The precise origin is an old family secret: All the mud is sourced from somewhere not too far from Bintliff’s home in South Jersey along the Delaware River. But just like his father and his grandfather before him, Bintliff can tell when the mud is the real deal, and so can just about any clubhouse attendant or pitcher or umpire in MLB. The reason that the Bintliff family has been able to make a business out of mud for decades now is simple: The mud they have found at this secret location is oddly perfect for rubbing down a baseball. It’s smooth—almost creamy—and when applied to a ball, it soaks right into the surface without dribbling off, improving the grip without creating too much discoloration.

Bintliff’s mud was first used by teams in the 1930s and has been league-wide since the ‘50s. (Officially, it’s Lena Blackburne Rubbing Mud, named for the player and manager, who was friends with Bintliff’s grandfather and started using the mud when he was a third-base coach for the Philadelphia A’s.) That’s a long time for any product to keep a foothold in a game that’s increasingly efficient and high-tech. Yet the last few years have finally ushered in what could be a fraught era for the mud business: In 2016, MLB first experimented with a prototype of a new ball that would not require mud, trying it out in the Arizona Fall League. The commissioner’s office has kept trying to figure out the right formula for that. Just this year, as reported by The Athletic, MLB ran experiments with different substances on balls in the Texas League and Southern League.

The league’s thinking is simple: Mud is messy. It’s inconsistent. There’s no way to ensure that every baseball will be rubbed down in exactly the same way. The process is dependent on 65-year-old Jim Bintliff, who gets the mud in buckets from that secret location and keeps what he finds in his garage, straining out twigs and leaves in trash cans. (His wife, Joanne, helps manage the logistics of the business.) Why wouldn’t MLB want to find an option that cuts out all of that?

This was true before last season’s snafu over sticky stuff—the illegal substances, such as SpiderTack, that pitchers were applying to baseballs to improve their grip and boost their spin rate. The crackdown on those products only increased MLB’s interest in finding something other than mud: If not a baseball that came out of the wrapper a little more tacky and a little less glossy, as was tried first in the Arizona Fall League in 2016 and briefly in Triple-A in 2021, then a universal gripping agent of sorts, as has been tried in the minors this year. That would hypothetically address the concerns of pitchers who feel the current ball is too slick without any other substances.

LEBRECHTMEDIA/Sports Illustrated

The problem? It’s hard to develop those options. There hasn’t been consistent feedback from players who have used anything other than a mudded ball. While MLB has been trying for years now to get it just right, there hasn’t been a breakthrough, and so the only choice for the majors is still mud—the same as it’s been for decades.

The memo that MLB sent to clubs on Tuesday underscores that idea. As reported by ESPN, the letter instructs teams on how clubhouse attendants should be rubbing down baseballs, along with more general information about ball handling and storage. The mud now must be applied on the day of the game in which the ball is used—previously, it might be done up to a few days in advance—and no more than eight dozen balls should be placed in one ball bag. The hope is that the guidelines produce more consistency.

“The fact that they’re trying to get a uniform process with the mud tells me that they know they need it,” Bintliff says when reached by phone on Wednesday.

He’ll miss the idea of clubbies who might have their own unique styles of mud-rubbing. But, for what it’s worth, he says the new instructions from the league are just about what he would do himself: two fingertips’ worth of mud, across the whole baseball, rub for half a minute.

LEBRECHTMEDIA/Sports Illustrated

As far as Bintliff is concerned, MLB can keep experimenting, even though he dislikes the way they’ve gone about doing it: If they haven’t found a replacement for his mud yet, he thinks, good luck finding one any time soon. And if not, well, “I have two words for them, and they’re not Merry Christmas,” cracks Bintliff. They can standardize the application process, but he doesn’t believe they can find a substitute for the particular magic of his down-home, old-school, hands-in-the-dirt product. The new guidelines are supposed to go into effect today. And on Monday? Bintliff’s going out to find some mud for next year.