Finally breaking a impasse, the Missouri Legislature gave final approval Thursday to new congressional districts that are expected to continue Republicans' electoral edge in a former swing state that has trended increasingly red.

Missouri had been one of the last states to enact new U.S. House districts based on the 2020 census. That's because Republicans who control both legislative chambers spent much of their session squabbling among themselves over how aggressively to draw districts to their advantage and which communities to divide while balancing the population among districts.

Facing a 6 p.m. Friday deadline to pass bills, the Senate voted 22-11 on Thursday night to approve a map passed earlier this week by the House. The Senate then ended its session, cutting off work on all other bills.

The redistricting legislation now goes to Republican Gov. Mike Parson to become law.

Because the new districts took so long to pass, Republican Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft has warned that local election authorities may not have enough time to accurately adjust everyone's voting addresses before ballots are prepared for the Aug. 2 primaries. As a result, he said it's possible that some voters could be given the wrong ballots.

Democrats and Republicans in many states have tried to use the once-a-decade process of redistricting to give their candidates an advantage as they battle for control of the closely divided U.S. House. But that hasn't worked out in all cases.

Courts in Florida, Kansas, Maryland, New York, North Carolina and Ohio all overturned maps that they said were illegally drawn. Legal battles continue in many of those states. New Hampshire is the only state besides Missouri that has not at least enacted a redistricting plan.

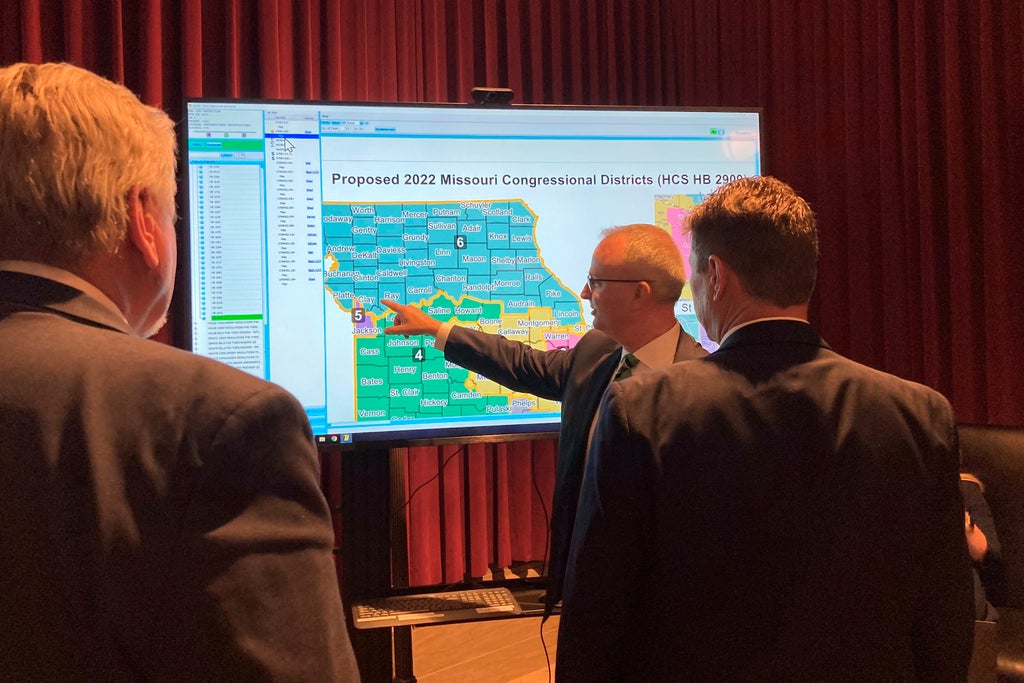

Some Missouri Republicans had pushed for an aggressive gerrymander that would have split up Democratic-leaning Kansas City and given the GOP a shot at winning seven of the state's eight U.S. House seats. But GOP legislative leaders feared that could backfire by spreading their voters too thin and ultimately opted for a plan that shored up their strength in the six districts they currently hold.

“I think gerrymandering is wrong no matter who does it,” Senate Majority Leader Caleb Rowden said while defending the map that passed.

Though he called it “a reasonably strong 6-2 map” for Republicans, conservative state Sen. Bob Onder criticized colleagues for not adopting an even more partisan plan. While lawmakers in other states were playing “hardball” on redistricting, “we're playing t-ball,” he said.

Missouri has just one congressional district that's relatively competitive — the 2nd District in suburban St. Louis, held by Republican Rep. Ann Wagner. Republicans made it a priority to fortify that district against Democratic gains.

The new plan strengthens the Republican vote share there by 3 percentage points over the current districts, according to an analysis by legislative staff that focused on top-of-the-ticket election results from 2016-2020.

Republican voting strength would be reduced by a similar margin in the nearby 3rd District, which wraps around the St. Louis area before stretching westward to central Missouri. But the GOP would still hold a sizable advantage there.

The redistricting plan also redraws the 5th District to focus more narrowly on the Kansas City area — aiding Democrats — instead of extending it into rural areas as is currently the case.

Some lawmakers said it didn't make sense to try to mesh Kansas City residents with rural voters.

“I believe the map does a good job of balancing all of Missouri’s regions and their different views and interests in various congressional districts,” said Sen. Mike Bernskoetter, chairman of the Senate's redistricting committee.

One of the communities most affected by the redistricting plan would be Columbia, the state's fourth largest city and home of the University of Missouri. A dividing line running through downtown would shift the university campus and the city's southern side into the 3rd District while the northern portion would remain in the 4th District that extends westward to the Kansas border.

Though some states began working on redistricting soon after the Census Bureau released data last August, Missouri waited until the start of its legislative session in January. The House quickly passed a plan, but the Senate didn't counter with its own version until March. The two chambers remained at odds as candidates filed for Congress without knowing the shape of their new districts. Several lawsuits have been filed seeking to compel action on new districts, though no court has yet intervened to order that.