A privately owned submersible carrying five people on a deep-sea dive to the wreck of the Titanic has been missing at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean since Sunday. Banging sounds, heard across 30 minute intervals, have now been detected by a Canadian seaplane, sending authorities scrambling to locate their source.

On Tuesday afternoon, the U.S. Coast Guard estimated that 40 hours of the vessel’s emergency oxygen supply could remain. The missing crew consist of Hamish Harding, a British billionaire and adventurer; Shahzada Dawood, a Pakistani-British businessman and his son, Suleman; Stockton Rush, chief executive and founder of OceanGate Expeditions ; and Paul-Henri Nargeolet, a French submersible pilot.

Here’s everything we know so far about the submersible, and what might have happened to it.

What is the Titan submersible?

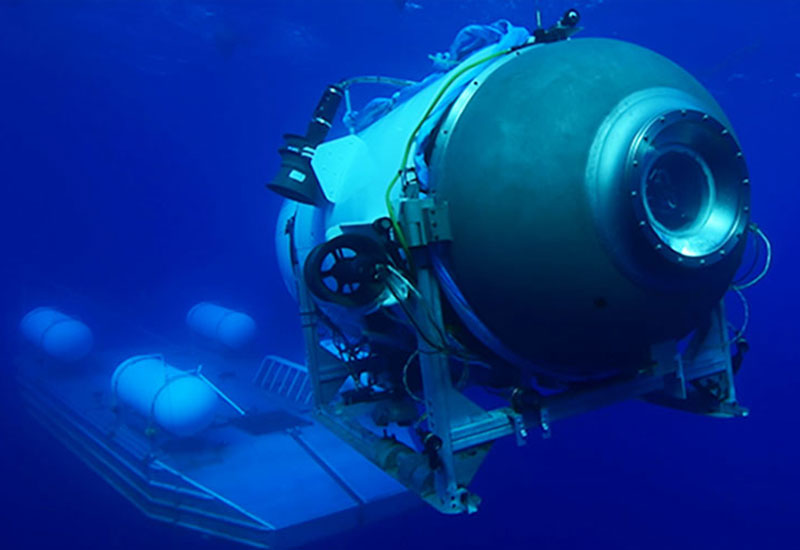

The Titan is a five-person research and survey submersible owned and operated by OceanGate — a private company that provides submersibles for commercial, research and military purposes, according to its website.

It is designed to carry up to five people, usually consisting of a pilot and four crew members. Built to dive to depths of 13,123 feet (4,000 meters) and travel at 3 knots (3.5 mph, or 5.6 km/h), the craft is 22 feet (6.7 m) long and weighs 23,000 pounds (10,400 kilograms).

Most major marine operators follow standards set by ship classification societies, although there is no legal requirement to seek classification.

The Titan is a custom-built vessel that has not had its design classified. Made from titanium and filament-wound carbon fiber, the submersible is bolted from the outside. This means that the crew inside cannot open it — to be let out, a team on the surface must unseal the hatch.

The submersible has four electric thrusters that are piloted with a Logitech gaming controller. OceanGate also uses Elon Musk's Starlink satellite technology during its diving operations. Titan has multiple methods to descend and return to the surface, including propellers; floatation tanks that are flooded with water or filled with air; and weights that can be dropped to provide positive buoyancy.

The crew members can see out of the vessel and into the deep-sea gloom thanks to an array of lights, a laser and sonar scanners, as well as externally mounted cameras. Passengers can also look out directly from the Titan's viewport, a pressure-proof window with an internal diameter of 12.3 inches (31.2 centimeters), making it the largest viewport of any deep-diving crewed submersible, according to OceanGate.

Pressure sensors on the sub monitor the structural integrity of its hull, which can "determine if the hull is compromised well before situations become life-threatening, and [enable the vessel to] safely return to the surface," OceanGate said.

What could have happened to the missing submersible?

It is too early to say what could have happened to Titan, though experts have suggested a number of potential scenarios as to how it went missing. These include power failure, hull rupture, adverse weather conditions, or the submersible getting snagged on a piece of the Titanic's wreckage.

Stefan B. Williams, a professor at the Australian Centre for Field Robotics at the University of Sydney, suggested that the "worst case scenario is that it has suffered a catastrophic failure to its pressure housing. Although the Titan's composite hull is built to withstand intense deep-sea pressures, any defect in its shape or build could compromise its integrity — in which case there's a risk of implosion," he wrote on The Conversation.

Williams also wrote that there could have been a fire on board, potentially from an electrical short circuit, and that could have stopped the submersible's electronic systems from working.

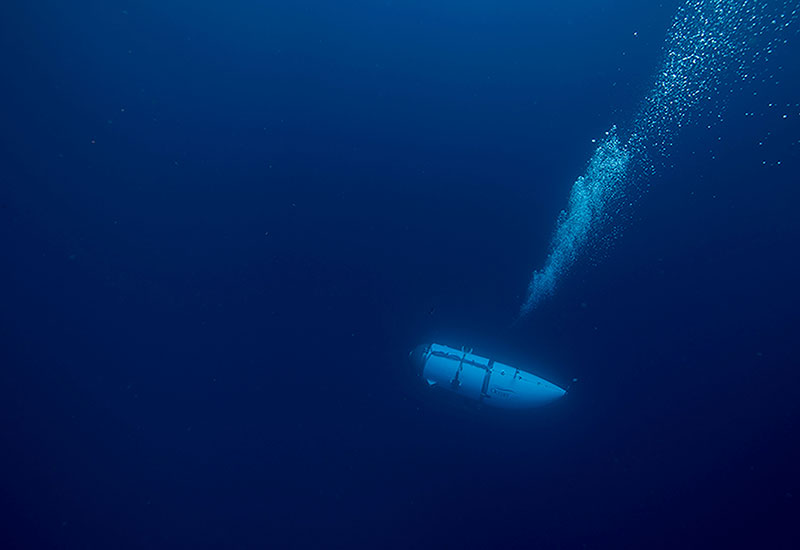

Support ships lost contact with the custom-built submersible roughly 1 hour and 45 minutes into its 2.5-hour descent to the Titanic's wreck, which is located 12,500 feet (3,800 m) beneath the surface and about 900 miles (1,500 kilometers) east of Cape Cod, the U.S. Coast Guard said.

The dive took place after a particularly harsh winter, during a brief reprieve from adverse weather conditions, Harding wrote before embarking on the voyage.

"Due to the worst winter in Newfoundland in 40 years, this mission is likely to be the first and only manned mission to the Titanic in 2023," Harding wrote on Instagram, June 17. "A weather window has just opened up and we are going to attempt a dive tomorrow. We started steaming from St. Johns, Newfoundland, Canada yesterday and are planning to start dive operations around 4am tomorrow morning. Until then we have a lot of preparations and briefings to do."

Another possibility is that the ship could have gotten lost after a communication breakdown between Titan and its surface ship, the Polar Prince. Titan relies on regular contact with the surface to navigate. According to a news report by David Pogue, a correspondent for CBS News Sunday Morning who took a previous trip on the Titan, the vessel had a prior incident of losing contact — leaving it lost for 2.5 hours.

Rear Adm. John Mauger of the U.S. Coast Guard's First District told reporters the Coast Guard is "working very closely at this point to make sure that we're doing everything that we can do to locate the submersible and rescue those on board."

How difficult will it be to find?

There currently appear to be two aircraft, a submarine and sonar buoys searching for the Titan, according to Williams. The U.S. Coast Guard said it has flown over an area roughly "the size of Connecticut" to look for signs of its surfacing. Williams noted the submersible would have had a transponder and transceiver to send and receive signals.

"This link allows for underwater acoustic positioning, as well as for short text messages to be sent back and forth to the surface vessel — but the amount of data that can be shared is limited and usually includes basic telemetry and status information," Williams wrote.

On Wednesday morning (June 21), a Canadian P8 Poseidon reconnaissance plane detected bangs made at 30 minute intervals, which were heard again four hours later.

Nicolai Roterman — a deep sea ecologist and marine biologist at the University of Portsmouth — told Live Science that the 30 minute intervals would "certainly be consistent with the idea of a trapped crew trying to contact the outside world, while at the same time conserving energy and therefore oxygen."

He added: "If this is the case, then it would indicate that the submersible is on the seafloor and either the system for jettisoning weight has failed, or Titan is snagged or trapped somehow.”

Yet attempting a rescue could prove challenging. The deepest ocean rescue in history — the 1973 recovery of the Canadian submersible Pisces III off the coast of Ireland — took place at 1,575 feet (480 m) below the surface — eight times less than the greatest possible depth Titan could be located at.

According to David Pogue, the sub lacks a sonar beacon to send emergency pulses back to the surface.

If the vessel is found close to the Titanic's depths, there are not many craft that could recover it. NATO's Submarine Rescue System (NSRS) has a maximum depth range of 2,037 feet (621 meters) for its remotely operated vehicles, likely putting the submersible far beyond its reach.

"Whether or not retrieving a submersible from 3,800 m depth is practical is another matter, given the roughly 10-tonne [11 short tons] displacement of Titan and the kilometers of heavy cable required, a very powerful winch would be needed… I’m unaware of any submersible retrieval from such depths," Roterman said.

What's the difference between a submersible and a submarine?

Unlike submarines, submersibles cannot launch themselves from port and return independently, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Instead, they rely on support ships to carry them from port to their dive sites and back.

Titan's support ship is the Polar Prince, which the submersible kept in communication with via regularly timed pings until contact was lost.

Due to the risks involved in the trip, passengers had to sign a death waiver before they embarked on the journey, according to Mike Reiss, an American television writer and producer who has been on a dive to the Titanic.

"To get on the boat that takes you to the Titanic, you sign a massive waiver that you could die on the trip," Reiss told BBC Breakfast. "On the list, they mention death three times on page one and it's never far from your mind. As I was getting on the submarine, this could be the end."