Lucknow, India – Ensconced in a bustling part of northern India’s sprawling Lucknow city is Lal Kuan, a predominantly Dalit neighbourhood.

The Dalits – who fall at the bottom of India’s complex caste hierarchy – are believed to be a loyal vote bank of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), currently led by Mayawati, the 68-year-old former chief minister of Uttar Pradesh state, whose capital is Lucknow.

And yet, in the narrow, winding bylanes of Lal Kuan, BSP symbols are missing, with the saffron flag of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu majoritarian Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) near ubiquitous in the area.

It is not much different nearly 230km (143 miles) away in Etawah, a small town in western Uttar Pradesh and a bastion of the Samajwadi Party (SP) of Akhilesh Yadav, another former state chief minister, who was in power from 2012 to 2017. There is little to be seen of the SP in terms of campaign props, and once again, saffron flags sit atop houses, commercial buildings and other establishments.

Uttar Pradesh is India’s most populous and electorally crucial state. In area, it is nearly as big as the United Kingdom and its 241 million residents are more than the total population of neighbouring Pakistan or Brazil.

With 80 of 543 seats in the Lok Sabha – as the lower house of India’s parliament is called – winning Uttar Pradesh is a key determinant of who rules nationally in New Delhi. Maharashtra, with the second-most number of constituencies at 48, comes a distant second.

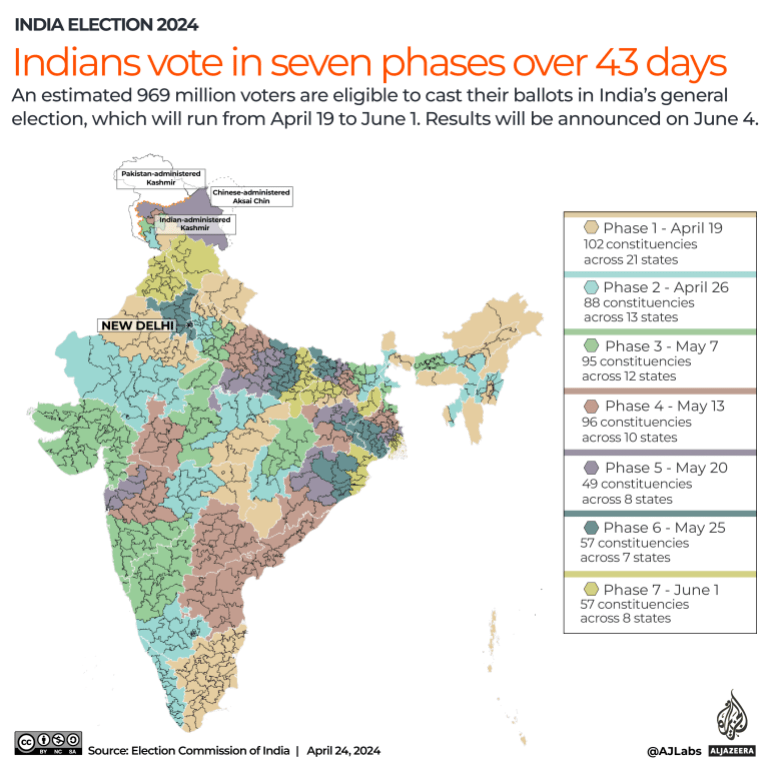

As India votes in crucial national elections, the battle to win Uttar Pradesh is on once again. In 2019, the BJP and its allies won 64 seats in the state, and a coalition of BSP-SP and another regional party managed 15. This year, the SP is a member of the main opposition Indian National Congress party-led INDIA alliance while Mayawati’s BSP is going solo.

But with the third phase of the Indian election coming up, both the SP and BSP appear to be missing in action. The near-absence of a spirited campaign or any visible publicity by the two parties reflects a larger challenge they together face – a significant erosion from Uttar Pradesh in the face of the spectacular rise of the BJP, which has been ruling at the centre since 2014 and in the state since 2017.

Missing in action

The SP and BSP once dominated the political landscape of Uttar Pradesh – each representing specific caste groups and with core supporters. The former counts on the Yadav community, who form roughly 9 percent of Uttar Pradesh’s population and are recognised as Other Backward Classes (OBC), a term that refers to lesser privileged social groups.

For the BSP, it is the Jatavs, a social group within the Dalits, who are broadly classified as the Scheduled Castes in the Indian constitution to make them eligible for various affirmative action programmes launched by the government. The Jatavs are about 10 percent of Uttar Pradesh’s population.

To a large extent, the SP, and to a more limited extent, the BSP, also count on Muslims, who constitute nearly one-fifth of the state’s population. The SP has been known for its MY – Muslim Yadav – caste combination.

It is because of these loyal groups that the SP and the BSP haven’t suffered a significant dent in their vote shares in Uttar Pradesh. However, while the two parties earlier succeeded in bringing more communities into their fold – allowing them to form governments – the trend seems to be reversed now.

Hiralal Kushwaha runs a small shop selling stationery, toys for children and other little knick-knacks in Bashirat Ganj, a sleepy hamlet in central Uttar Pradesh’s Unnao district. It is a hot afternoon and with no customers in sight, Kushwaha, in his late 30s, is sitting alone in his shop, sipping tea from a plastic cup while scrolling on his mobile phone.

“The BJP government focuses too much on religion, which can hardly solve real-world problems. As Uttar Pradesh’s big parties, SP and BSP should have been able to offer an alternative to that. I’m not very comfortable with politics of religion, but the current state of the two regional parties has meant the voters like me are not left with many alternatives,” he told Al Jazeera, shaking his head in despair.

So, what went wrong with the two parties and why are they not being seen as alternatives to the BJP?

The Samajwadi Party’s challenges

The SP was founded by Mulayam Singh Yadav, a wrestler-turned-socialist, in the early 1990s. Samajwadi in Hindi means “a socialist”, and the party workers wear red caps to signify that.

Yadav served as Uttar Pradesh’s chief minister for three terms – none of them for a full five years. His son Akhilesh was the chief minister from 2012 to 2017 before the BJP retook the state. Yadav died in 2022.

BSP chief Mayawati, meanwhile, is a four-time chief minister – three brief stints and one full term from 2007 to 2012.

The two parties first formed a coalition to run the state government in 1993 before parting ways in 1995. After nearly 25 years of rivalry, the two again came together during the 2019 national election to take on a resurgent BJP, but could not make much impact.

In the 2022 state assembly election, the once-powerful BSP was reduced to just one of the 403 seats while the SP did reasonably well, winning 111. The BJP and its allies won a comfortable 273 to form the government.

Across Uttar Pradesh, voters spoke to Al Jazeera about this shift in the state’s politics, their understanding of the decline of the SP and BSP – and the rise of the BJP.

As is common across India, especially in small towns in the mornings, Rakesh Malik, Dhruv Kumar and Robin Chaudhary – a group of men – sipping hot ginger tea as they discuss politics animatedly at a roadside tea stall on the outskirts of Bulandshahr town in western Uttar Pradesh.

As they recall the Akhilesh Yadav-led SP government’s tenure, they stop on a hot-button issue: crime. The party is often accused of flirting with musclemen-turned-politicians, known as “baahubalis” in the local language.

“The law and order situation under the SP government was hopeless. Lawlessness was the order of the day and the crime rate was extremely high. Nobody felt safe, especially our women. It has improved drastically under [BJP] Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath,” says Kumar as others nod in agreement.

Adityanath, a saffron-clad monk known for his hate speeches against Muslims and other minorities, was the BJP’s surprise pick for the chief minister in 2017. Since then, he has emerged as a top BJP leader and a “star campaigner” for the party.

In the heart of a crowded Mathura city, an hour away from the famous Taj Mahal, a feisty Manju Singh sits in her husband’s tiny tea stall, her head covered to shield her against the scorching afternoon sun.

“We could barely step out of the house without being harassed, especially after dark. I am not very young and yet I was teased. Our younger girls were even more traumatised, their dupattas snatched away with impunity as they returned from schools or colleges. Akhilesh Yadav did nothing for our safety,” says the 51-year-old.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau data from 2022, the crime rate in Uttar Pradesh stood at 171.6, significantly lower than the 258.1 for the entire country. The data also shows kidnappings in the state have been on a decline since 2018 and have been below the national average since 2019. The same data shows violent crimes peaked in the state in 2016, with about 30 such crimes per 100,000 population, which in 2021 dipped to 22.7.

Even the Yadavs, who otherwise remain steadfast in their support of the SP, acknowledge the criticism.

Dayanand Yadav, in his early 40s, is visiting a friend who runs a saree shop on the outskirts of Amethi town – the family bastion of the Gandhis, India’s most prominent political family that gave three prime ministers – Jawaharlal Nehru, the first ever PM, his daughter Indira Gandhi and her son Rajiv Gandhi. Rajiv’s Italian-origin wife Sonia Gandhi and their son Rahul are both parliamentarians and have been presidents of the Congress party.

Amid a sea of colourful polyester sarees, Dayanand introspects about the party he has always supported.

“As Yadavs, we are always associated with the Samajwadi Party, even if we vote for someone else. So, we continue to support them because of the caste affiliation. However, it is true that governance and law and order under the Akhilesh Yadav government was terrible,” he says.

“There was something about Mulayam Singh Yadav, which Akhilesh does not have. Mulayam was pragmatic and astute, Akhilesh is amateurish.”

But it is not just its dismal record on law and order that completely explains the SP’s decline.

Chandrachur Singh, professor of political science at Delhi University’s Hindu College, thinks the SP failed in cultivating a diverse leadership beyond familial ties and its “narrow focus” on the Yadav and Muslim communities allowed the BJP to “portray it as catering to exclusive clan-based interests”.

“In contrast, the [BJP’s] emphasis on Hindu nationalism and the endeavours towards constructing a Ram temple serve as significant drivers of its support,” he said, referring to the grand temple in Uttar Pradesh’s Ayodhya town Modi inaugurated ahead of the election.

The temple was built on the site where a 16th-century mosque was demolished in 1992 by a Hindu mob, which claimed the Mughal-era structure stood at the exact place where the Hindu god Ram was born. The temple issue was turned into a mass movement by the BJP in the 1980s, resulting in frequent communal riots and catapulting the party into India’s political mainstream.

Where Mayawati’s BSP lost the plot

If the SP is remembered for its alleged poor governance and law and order failures, Mayawati’s tenures as Uttar Pradesh chief minister were admired across a cross-section of voters for their strong administration and reduced crime. “Behenji” (elder sister) was praised even among the non-Dalits for it.

Seema Sharma of Bulandshahr, a lawyer in her mid-40s, is eager to talk politics as she rifles through some papers outside a shop selling eatables.

“I am a Brahmin [most privileged Hindu caste], but I really want to see Behenji back in power. The governance under BSP was very good and the administration was firm. Government officials would take their work seriously and put in long hours to keep the state running. We felt extremely safe as women,” Sharma told Al Jazeera with a glint in her eyes.

Even the BJP supporters agree with her. “We are BJP supporters but we do admit that the BSP government was very good,” says Robin Chaudhary.

There is a reason for Mayawati’s acceptance even among the so-called upper castes. Her victory in the 2007 state election was attributed to her clever formula of bringing the Brahmins and the Muslims together with the Dalits – a departure from the BSP’s traditional anti-upper-caste and anti-Brahmin politics. However, she was forced to go back to her original vote bank after many Dalit groups accused her of diluting the BSP’s core agenda. Meanwhile, the Brahmins and the Muslims largely went with the BJP and the SP respectively.

The BSP is now faced with corruption allegations, an exodus of its senior leaders to other parties, and the near-decimation of the party’s organisation on the ground.

“The BJP’s rise can be primarily attributed to the BSP’s inability to capitalise on the foundation laid by Kanshi Ram and his movement advocating for the empowerment of the Dalit community,” said Singh, the political science professor. Kanshi Ram, a prominent Dalit leader and BSP founder, died in 2006.

“Mayawati’s prioritisation of personal wealth accumulation over the core issues, coupled with her associations with the land mafia and real estate developers, proved to be detrimental to the BSP,” Singh added.

Back at Lucknow’s Lal Kuan, the disappointment with the BSP is palpable on a sweltering afternoon.

Shobhna Kumari, 24, is about to pick up her siblings from school. As she engages in an impassioned political conversation, reluctant to pause midway, her father is forced to take off alone to bring the children home.

“We belong to the Dalit community, so obviously we vote for Behenji. But the party seems to be in shambles. Please look around. It’s the election season and this is a core area for the BSP, but do you see any flags or banners? All you see are these flags [pointing to saffron flags on houses], which have nothing to do with our politics, and which political strongmen have come and hoisted,” Kumari tells Al Jazeera.

A few metres away, Deepu Chandra and Rajender Jaiswal tend to an abandoned stray puppy in Chandra’s grocery shop. As they feed the dog and give it water, they talk politics, more specifically of the BSP.

“We belong to a Scheduled Caste community and most of us continue to steadfastly support the BSP, irrespective of who the candidate is. However, people have started worrying now that voting for BSP might mean wasting their votes. Behenji just does not seem interested any more, and there is nothing left of her party. We hardly even hear much of her now,” says Chandra.

“It almost seems like the BSP is sitting it out this election and that disappoints us,” chips in Jaiswal.