Generation X and their little brothers and sisters have hit middle age and it’s not pretty. Turns out not ending up resembling your Boomer parents is harder than you might think. We should have realised mid-life disquiet for Gen X would usher in existential crisis – we’re good at it.

Gen X are not the first to get angsty: wrestling with the trials and tribulations of reaching a half century has a long literary history. (Dante’s mid-life crisis gestated the Divine Comedy). But maybe humans are talking about the halfway region like never before because women are having a say – the eight rings of heaven and hell reconfigured as variant doses of HRT. A significant cultural shift scholars are identifying as the “menopause moment”.

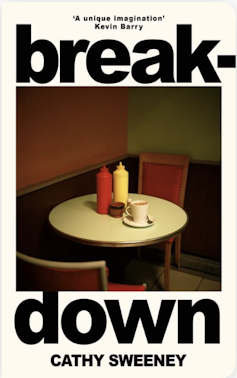

Review: All Fours – Miranda July (Allen & Unwin), Breakdown – Cathy Sweeney (Hachette)

With the purgatory of peri and full-blown menopause playing out dramatically in literature, film and TV, “The Change” is moving out of euphemism territory. From a resplendent Julianne Moore in Gloria Bell to Kristin Scott Thomas’ viral “meno-monologue” in Fleabag, women are variant hues of mad, bad and angry; bored, funny and horny AF – their stories tied into the social and economic conditions of the times – their sex reconfigured beyond the male gaze.

Two recent book releases All Fours by American art darling Miranda July and Breakdown by Irish writer Cathy Sweeney swagger unapologetically into this arena.

Both novels begin remarkably similarly. A middle-aged woman fed up with the unrelenting sameness and routine of the contemporary everyday gets in a car and drives away from her life and family. One comes back. One leaves for good. The scandalous nature of their manoeuvres is captured by the opening lines of Breakdown: “Mothers are not supposed to go on road trips”.

Mothers can go on holidays, city breaks, outings, but not road trips. It is women without children who go on road trips. When a Mother leaves home, she is expected to return, sooner or later, with shopping bags. And there are good reasons for this. Driving on a motorway, or travelling by train or bus or ferry, or taking a lift from a stranger or spending a night in a cheap motel, a Mother might take a break from the story that she is telling herself about the life that she is living. And then what?

Both narrators remain nameless, allowing readers to enter their tumultuous head-spaces without specific restriction.

July’s heroine, mum to seven-year-old, non-binary Sam and wife to music producer Harris is a semi-famous artist flush with cash from a commercial job. She tells her husband she’ll drive from Los Angeles to New York as a kind of self-seeking adventure except she never gets there. She pulls over less than an hour outside of LA in a smallish town and falls deeply in lust with Davey, a guy half her age cleaning her windscreen.

A surreal series of interactions with him unfold (including paying all the money she was gonna spend on the road trip to his wife to decorate the gross hotel room she spends two weeks in) but the two characters never consummate their mutual desire. Their chaste sense of connection, and Davey appearing convinced that no penetration absolves him from betrayal, are both absurdly funny and oddly moving.

Physically we were always on the edge of something new […] I lifted his shirt and kissed his chest. The tiny nipple hairs. Then slowly I moved all the way down to the band on his underpants, which I thought would be boxers but were white and tight and made me lose my mind a little. I unbuttoned his jeans and he only said Fuck under his breath […] I couldn’t believe I was down here and I wanted to stay forever. Just build a little hut right by the side of his dick and live there for the rest of my days.

Sweeney’s protagonist heads down a much darker road. A retired teacher, mum to two grown kids and a “failed” artist (just another woman in a long line who “postponed” her artistic pursuits to raise a family or make some money) walks out of her comfortable house in Dublin one morning and never returns. She journeys by car until she ditches it in a shopping centre, then she takes a ferry – a crossing we realise she will never make again.

Sweeney’s character is shedding, she no longer wants to answer calls or get anything “done”, she doesn’t want to desire or buy things she doesn’t need, she wants to live simply and essentially and so she rents a run-down cottage from one of the handful of men she has strange allegorical interactions with and we know it’s likely she’ll spend the rest of her days there.

Shades of transgression

Compared to Breakdown, All Fours is an innocent foray into transgression. There’s an infantile quality to the narrator’s obsessions – a woman we invariably read as July because we can’t not – her bio and life story the blueprint. This makes for some laugh out loud moments but no one really does anything wrong.

When transgressions are made there’s a lot of hand wringing, confession and discussion. Verbal contracts get drawn up. People get sat down. The arrangements made between husband and wife while interesting in terms of a critique of the marriage contract are rather uninspiring.

Harris has Mondays with his lover. She has Wednesdays with hers. I get there’s a kid involved – so scheduling of the universe is required (I’ve lost too many minutes of my life staring at the laminated schedules attached to the fridges of my married-with-children friends in utter despair) but the excel spreadsheet vibes are not exactly swoon worthy.

Breakdown’s heroine is fiercer and more fearless. People really do fuck; people are forsaken and left (including kids) and the narrator point blank refuses to talk to anyone about it for a long time. Some might find this version of disengagement bleak or even depressing. I found it enriching and exhilarating.

If you’re really tired of the roles you’re playing for other people best not to reinvent the wheel. Breakdown is funny too, albeit in darker more sardonic ways – the absurdities of contemporary life on show superbly in both books.

In All Fours when the character returns home, bereft that her time with Davey has come to an end, she bumps into her neighbour. While they make small talk, she imagines telling him about what she’s going through and her neighbour, in turn, offering to take her in:

Think of our house as a half-way house […] a chance to pull yourself together […] just eat and sleep and let your unconscious do the work. While you’re sleeping, we’ll say prayers and do various energy moving rituals to help you with the transition.

In Breakdown, Sweeney uses found language, signs, posters, lists, texts and graffiti, which appear in bold in the text and are often reconfigured for wry comic effect – TIREDNESS KILLS – TAKE A BREAK or BEWARE OF GOD’S TERMS AND CONDITIONS.

The difference between the two books is that Sweeney sustains the engagement beyond farcical situations and cracker one liners, our connection to her lead character extends and expands, opens out in ways July just can’t do. In All Fours we walk away not really convinced, in Breakdown the character stays free and unrepentant.

The closing scenes of Breakdown read like a literary still life.

There are days when loss is everywhere, attached to no particular thing – to my clothes hanging on the line, to the small collection of secondhand books on the shelf in the alcove, to the wildflowers in a vase on a table. But nothing lasts. Soon the sense of loss fades, and the world returns to nothing much at all. It is easier than it should be not to think about the people you love.

Breakdown is stunningly good – a fulsome experience of a writer in control.

Self-aggrandisement

The first third of All Fours is near perfect and should have been the last – in a recent New Yorker interview July confessed she didn’t know where to take the novel beyond the initial premise and it shows.

Everything after Davey is a letdown. Gestural – over thought and performative. As July starts throwing everything at us, too preoccupied with brilliantly capturing the mid-life woman zeitgeist, we don’t buy any subsequent plot turn or relationship she’s in.

The sudden pivot to not just sleeping with but having a full-on obsessive relationship with a hot dyke she sees across a room at an art opening feels rushed and convenient. When the breakup happens we’re relieved. For the lover. Because by this point, without the depth emotional register provides, the character has gotten manic and annoying. Self-aggrandisement seems to be the ultimate project.

Most reviewers of All Fours have spent more time referring to and unpacking July’s body of work than critiquing the book. July is a multi-form, multi-play artist sure but does this carnivalesque buffet of previous offerings distract? The tinge of her celebrity, downplayed in the novel so as not to alienate the ordinary, casts a golden light some appear not to be able to see through.

Perhaps others will find July’s familial transgression relatable. Clearly some consider her take as wild and brave. Tampons reconfigured as erotic items, mutual masturbation the new consummation. For me reading All Fours was in the end like being stuck in the quirk porn nightmare of an ego maniac.

In interviews July appears at pains to point out she’s not dancing in front of the mirror in this work when she nearly always is. In a recent Instagram reel, she was doing exactly that, naked in a hotel room, a sheer gauze of some sort providing a discreet filter – echoes again – of the novel being performed – self-referentiality on loop – her hot (despite the peri-menopausal drama) bod on full display, a potential Only Fans moment if it wasn’t so well lit (and if it wasn’t Miranda July).

And all this self-push is fine I suppose for eight seconds on Insta but not what this reader wants for over 300 pages in a novel. July’s aversion to any acknowledgement that she might be infatuated with herself more than anything else is disingenuous. As if “Big L” literature requires a distance from the auto-fiction that defines nearly all her work. To remove yourself from the frame now because it provides an apparently greater depth of artistic legitimacy reads as shadow play.

Sally Breen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.