"Miracle on 34th Street" is one of those distinctive holiday classics that also happens to be a good movie. The film is celebrating its 75th anniversary in 2022 and is remembered today for its obvious sentimentality and its half-hearted critique of the over-commercialization of Christmas. But one of the film's subplots reflected real anxieties about an issue that is just salient 75 years later – home ownership.

The film was a bright spot in an otherwise dismal period for Hollywood.

Given the recent stories about the obstacles first time home buyers face in 2022, from a record-low inventory earlier in the year to spiking mortgage rates last month, looking backward to a time when our country was in the grips of a truly transformational housing crisis offers some important insights. The film industry reflected the concerns of the immediate postwar era and helped to assuage the anxieties of a frustrated public that, like "Miracle on 34th Street's" young protagonist, dreamed of a home.

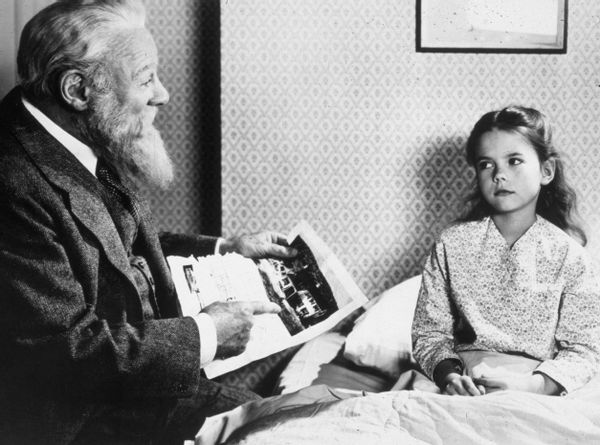

In the film, young Susan Walker (8-year-old Natalie Wood) lives with her mother in a high-rise apartment in Manhattan. Her mother Doris (Maureen O'Hara) is a divorcée (rarely depicted in films of the period) and a driven career woman who works for the corporate office of Macy's Department Store. Doris has brought Susan up to be practical and is ardently against anyone filling her daughter's head full of "legends, myths, or fairy tales." Susan is drawn to "Kris" (Edmund Gwenn in a role that would win him the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor), an older man her mother has recently hired to portray Santa Claus after the original shows up drunk to the Macy's Thanksgiving Day parade. Kris soon wins Susan and her mother over with his charming and affable personality.

One evening after dinner, he asks Susan what she wants for Christmas. She is hesitant but finally shares that she would love nothing more than for her and mother to move into a real house. She pulls a picture of a real estate advertisement out of her dresser drawer, shows Kris a picture of a quaint, cozy Cape Cod-styled home, and declares that the only way she'll believe that he's Santa Claus is if he can get her that house. Big demands for such a little girl! By the film's end however, Susan, her mother, and her mother's boyfriend and Kris' lawyer Fred Gailey are driving out to Long Island when Susan suddenly sees the very house she's asked for. A "For Sale" sign hangs out front. They stop the car and Susan runs in, claiming that this is "their house." The two adults look at each other with confusion and Susan continues to insist this is the very house she's asked for. A final shot of Kris Kringle's cane in the corner of the living room seems to confirm that he's delivered on his promise, and Susan, Doris, and Mr. Gailey will live happily ever after, not only as a new family, but also in this home which for many film audiences must have symbolized the suburban ideal.

"Miracle on 34th Street" was initially released in May of 1947. Darryl F. Zanuck, studio head of 20th Century Fox believed that audiences tended to stay away from movie theaters during the winter months. He thought a summer release would result in higher profits. Consequently, hardly any mention of Christmas or Santa Claus was made in marketing the film. Despite this, "Miracle on 34th Street" was a financial success and received glowing reviews from publications like The New York Times where its longtime film critic Bosley Crowther wrote that it was, "the freshest little picture in a long time, and maybe even the best comedy of this year."

And the film was a bright spot in an otherwise dismal period for Hollywood. By the following year in a bleak review of the 1947 box office, editors at Life wrote, "Since the invention of the cinematograph, hardly a movie season has seen the bad pictures so heavily outweigh the good." The article acknowledged the toll of the House Un-American Activities Committee on the industry's creative output, along with a diminished foreign market for American films. "Miracle on 34th Street" remained popular however, even almost a year after its release with the magazine's editors writing in the same piece that the "unheralded little picture about Santa Claus was [the] funniest and most original" of the year.

Given the context of the late 1940s, "Miracle on 34th Street's" success should not be surprising. Susan's Walker's ultimate desire for a home tapped into a yearning countless Americans also had for a single-family home after years of austerity, sacrifice and frugal living brought on by the twin traumas of the Great Depression and World War II. This collective expectation and unprecedented demand contributed significantly to a national housing crisis despite the Roosevelt and subsequently, the Truman administration's passage and implementation of the G.I. Bill. In November of 1945, the legislation was amended so that ex-servicemen could have easy access to low interest home loans. But veterans and their families soon realized that there was a severe shortage of homes available to actually buy.

Susan's Walker's ultimate desire for a home tapped into a yearning countless Americans also had for a single-family home after years of austerity, sacrifice and frugal living.

And so, from 1946-47, the nation found itself in the throes of a dire housing crisis brought on by a convergence of factors beyond simple supply and demand. Low home inventory was exacerbated by a shortage of building materials, a robust black market in the home building industry and numerous battles between private enterprise and the federal government about how new home construction should be financed. In April of 1946, the editors of Fortune devoted their entire issue to the housing industry, at various points championing the Truman administration's plans, questioning the federal government's role within the industry, pondering how prefabricated homes made of unconventional materials like aluminum or porcelain might shake things up, and profiling well-known builders across the country.

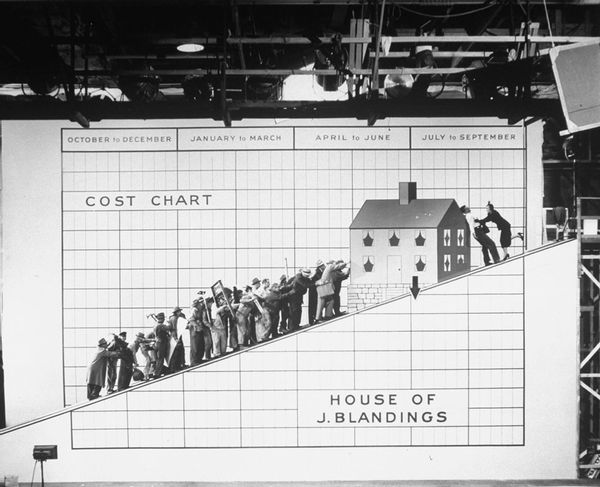

The magazine also included a short story written by Eric Hodgins, the former managing editor of Fortune who had worked his way up to an executive position with Time, Inc. The short story was titled "Mr. Blandings Builds His Castle" and it breezily chronicled the real-life experience of Hodgins and his family as they remodel a run-down country house in the wilds of Connecticut. Costs spiral out of control; hilarity ensues. The story struck such a chord with readers that it was adapted into a film two years later, becoming "Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House" and starred Cary Grant as the title character.

Like "Miracle on 34th Street," "Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House" (1948) intertwines the happiness and satisfaction of the family and traditional family roles with the depiction of single-family homes. Indeed, the immediate postwar period saw a significant increase in discourse around the "Dream House," best embodied by the proliferation of model homes that worked to stoke the desires of a consuming public anxious to participate in the frenzy of home buying that marked the latter half of the decade.

These films also promised something else a bit more intangible – community. As landscape architect Gregory Randall has noted, "the perception of the village, where everyone could own their own home, walk to school or town, and live not just among neighbors but among friends, became a deep desire which would fuel the dreams of young families across the nation." Whether a colonial manor or modest Cape Cod, the ways these films juxtaposed the prospect of home ownership with stark visions of the alternative – the concrete jungle and isolating nature of the big city, further demonstrated the allure of suburban living for many families.

A new era in home construction came to define an entire generation of family life.

For example, when the audience first encounters Susan, she is watching the parade from a high-rise apartment owned by Mr. Gailey, a young lawyer who is interested in dating her mother. Susan is depicted as intelligent, but lonely and somewhat socially awkward with children her own age. Through her friendship with Kris Kringle, she essentially learns how to be a kid, and yearns for nothing more than that house with a big back yard, a tree, and a swing. The audience of 1947 is also naturally led to conclude that Susan would thrive in such an environment and that the notion of community symbolized by suburban living would significantly aid her social development.

As Louis Hyman has argued, in the immediate postwar period, the embrace of consumer debt made the "good life possible," and eventually enabled the postwar housing boom of Levittowns and "little boxes" after the Truman Administration made its peace with the home builders by lifting price controls, the availability of low interest home loans became widespread, and supply chain bottlenecks were eventually resolved. A new era in home construction came to define an entire generation of family life.

However, the readily available access to credit did not come easily to everyone. African Americans were forced to borrow at much higher rates than their white counterparts to achieve their slice of the American dream, the promise of home ownership. In both "Miracle on 34th Street" and "Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House," it is no surprise that African Americans have a minimal presence – they are depicted as the domestic help. In actuality, African Americans enthusiastically moved into suburbs to carve out their slice of the postwar American dream. They just faced more challenges and obstacles from financial institutions unwilling to lend or developers who denied them the opportunity to move into many of most well-known new neighborhoods and subdivisions. Levittown, Pennsylvania, for example did not allow African American families in any of its developments until 1957 when William and Daisy Myers bought a home from a progressively minded white couple who were committed to the cause of integration. The Myers were harassed so mercilessly that they stayed in Levittown for only four years.

Another way then to understand the cultural power of film like "Miracle on 34th Street," of the way it taps into that desire for the perfect home, is as a kind of whitewashing of the more complex realities that many Americans dealt with as they adjusted to a new, uncertain era in the years immediately after World War II. In many instances, they faced obstacles to achieving their dream of home ownership that were simply beyond their control. In the 21st century, we also view films like "Miracle on 34th Street" through the veil of nostalgia. It is endlessly re-aired on cable television or is there waiting for on-demand viewing in the streaming age. In light of our nation's current challenges when it comes to home ownership – both the pleasures and pitfalls – it is crucial that we consider how the American dream and the American home became so closely intertwined.