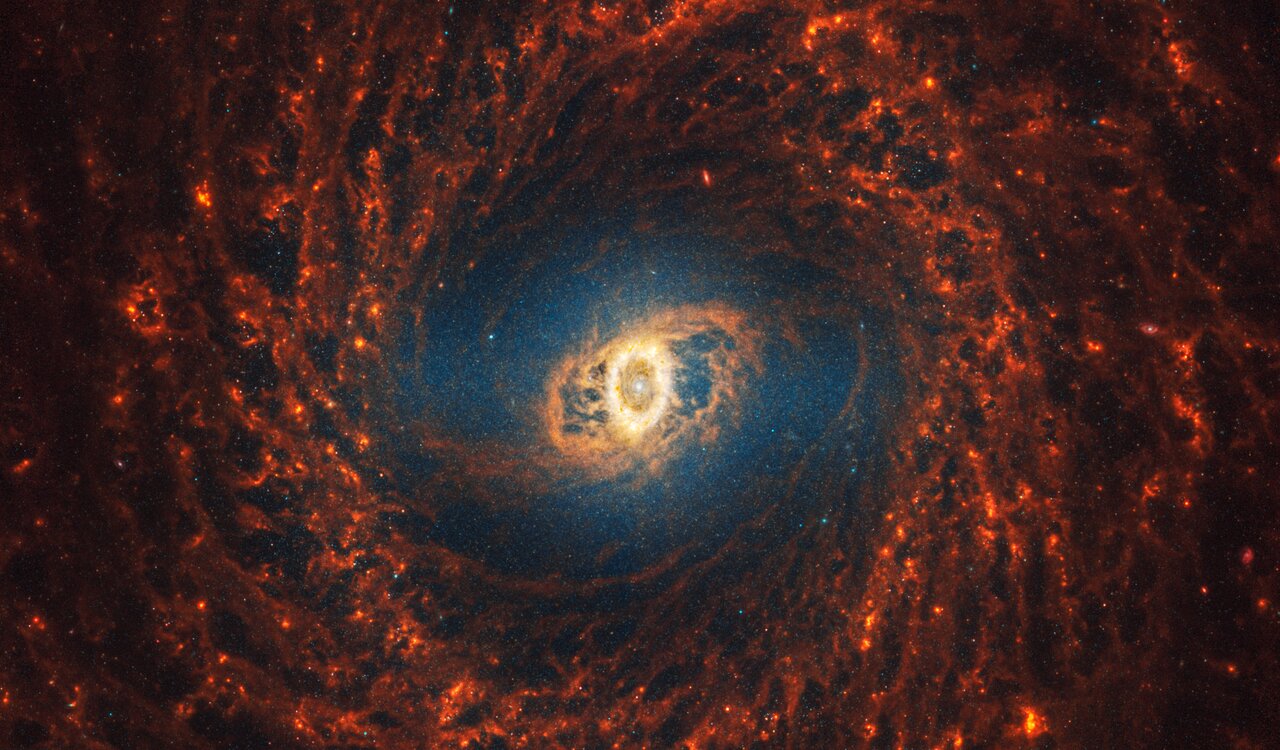

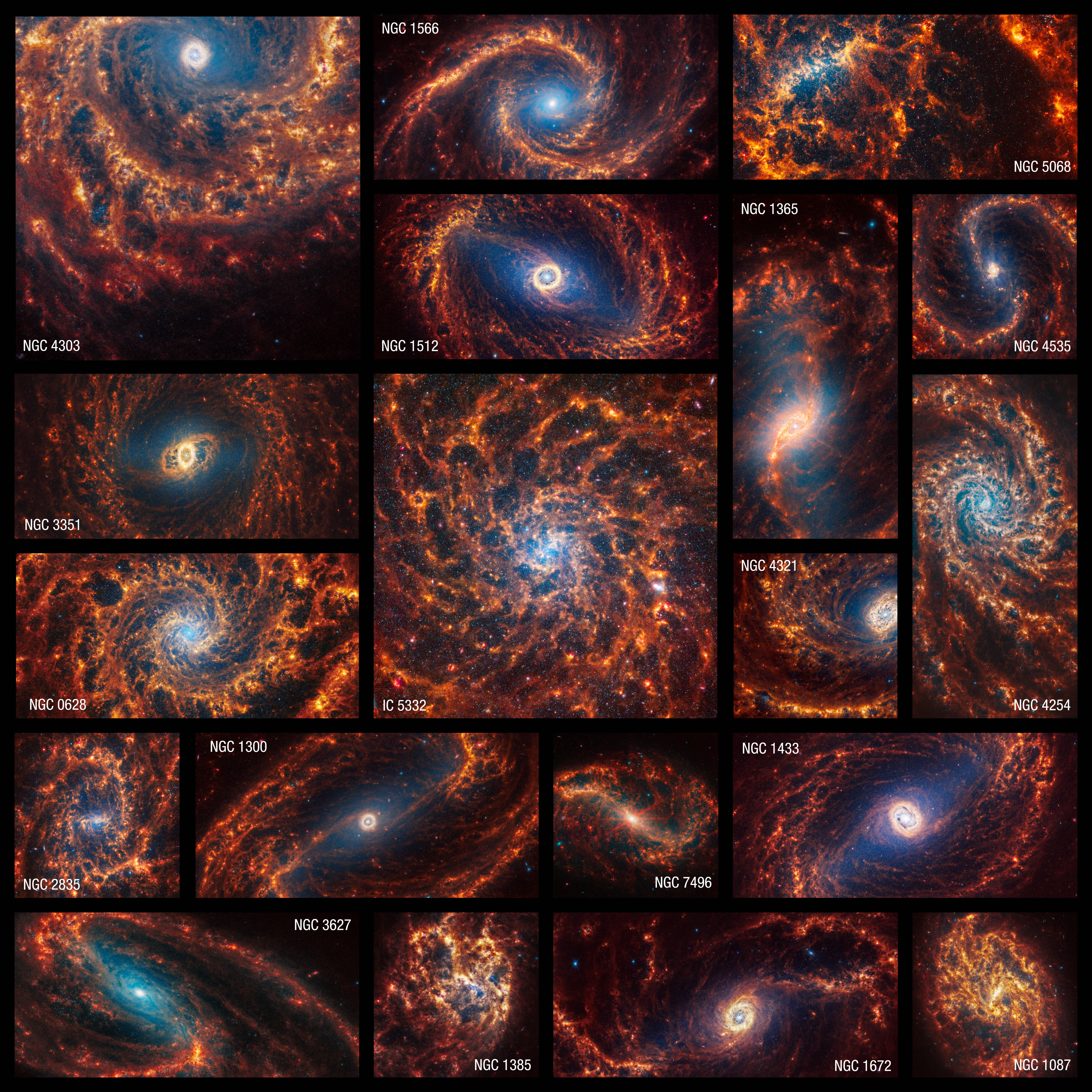

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has revealed images of 19 Milky Way-like spiral galaxies, showing stars, gas and dust in stunning detail. The images show the galaxies at the smallest scales ever observed outside our own galaxy.

"Webb's new images are extraordinary," Janice Lee, a scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore and a member of the team that is studying the images, said in a NASA statement. "They're mind-blowing even for researchers who have studied these same galaxies for decades."

JWST, which launched on Christmas Day in 2021, is unique in its ability to capture images of objects so distant and at this level of detail. Near- and mid-infrared cameras allow the telescope to "see" light in the infrared spectrum, which is invisible to the human eye. That lets scientists visualize dust clouds and the objects hidden within them — or objects so far away that the light they emit is far too faint for normal telescopes to see.

Related: After 2 years in space, the James Webb telescope has broken cosmology. Can it be fixed?

The spiral galaxies captured by the telescope range in distance from 15 million to 60 million light-years away from Earth, Reuters reported. The images show these galaxies brimming with stars, which appear as blue pinpricks of light. Some of those stars are scattered throughout pinwheel-like "arms" characteristic of spiral galaxies, while others cluster in the center of the galaxies. Evidence suggests that spiral galaxies grow from the inside out, so these blue clumps at the galaxies' cores likely indicate older star clusters, while the arms likely contain younger stars, according to the European Space Agency.

Also visible in the images are clouds of red and orange — dust that surrounds the stars. Spherical shapes may indicate the remnants of exploded stars. In some of the images, pink and red emanate from the galaxy cores. That light may come from supermassive black holes, huge concentrations of matter with masses hundreds of thousands of times that of our sun.

The new images were taken as part of a long-standing project, the Physics at High Angular resolution in Nearby Galaxies (PHANGS) survey. The ultimate goal of the project is to better understand the physics of how stars form. The "unprecedented" number of stars captured within these images are helping the PHANGS team achieve that goal.

"Stars can live for billions or trillions of years," Adam Leroy, a professor of astronomy at The Ohio State University in Columbus and a PHANGS team member, said in the statement. "By precisely cataloging all types of stars, we can build a more reliable, holistic view of their life cycles."