Milisuthando is a debut feature length documentary film by Milisuthando Bongela. Taking the form of a personal essay, it’s an intimate story about family and ancestors, about “inside apartheid’s experiment” and negotiating the complex world of post-apartheid South Africa.

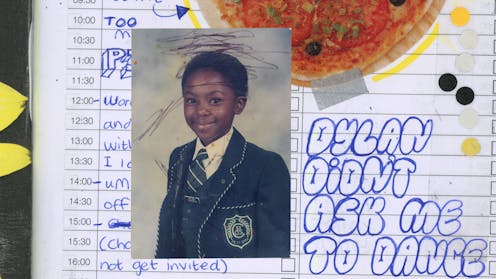

Bongela, born in 1985, offers a version of her life story in five parts organised poetically and thematically. The film is built on her experience of being born in the former Transkei “homeland” – one of the “independent states” designated by the racist apartheid government to institutionalise “separate development”. It explores what it means to have grown up in this society.

The details of Bongela’s life emerge largely in conversation with others – Black school friends at previously white schools, current white friends and family, including her 90-year old grandmother. In the process the film offers images of middle-class life beyond the much more familiar images of violence and unrest in Black townships.

Milisuthando premiered to critical acclaim at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival and is winning hearts on the international festival circuit.

As a lecturer and scholar who specialises in documentary film, my view is that Milisuthando defies conventional documentary storytelling to expand the canon of South African cinema. Its rich and challenging subject and audiovisual language offers an opportunity for South Africans to talk to each other in a way that is transformational. I asked the film-maker about her project.

Julia Cain: How would you describe your film for South African audiences?

Milisuthando Bongela: This is who we made the film for. It’s extremely South African and very intentionally sewn together over many years in conversation with who we are as a people and who we’ve become as a result of our history. It’s a meditative exploration of love and what it means to be human.

I found that there wasn’t enough of a reference point for my homeland existence in the public discourse. When we talk about Blackness and apartheid, I was always finding that, wait a minute, I didn’t grow up in the township – I grew up in another expression of racial division.

Julia Cain: Your film strikes me as a collage. What’s behind your formal choices?

Milisuthando Bongela: I had to drop the prose and pick up the poetry. We were like, let us rely on cinema, which uses images, light and sound. The approach was to do associative editing – put one image next to another and see what the viewers pick up. We want the audiences to go inside themselves. We knew we had to break with traditional form and invent our own.

Visually, we had such incredible material. I’m an aesthete. I believe in beauty as a way to enter into the world. A lot of times documentaries rest on the laurel of their messages. I’ve worked in fashion and art, and I do believe that aesthetics – whether it’s sound, whether it’s visual – helps to hold people and deliver what one wants to say. Because, we are talking about ugly things; we’re really engaging with painful histories. And not to gloss over that pain, but to help people enter and go quietly, deeply, because usually we look away.

The film is also commenting on what cinema has been to Black people in Africa – how we’ve been used as subjects and not necessarily as people with the power to take this technology and do with it what we wish.

Julia Cain: You’ve been very conscious of collaboration. Can you share how you worked with your old school friends, for example?

Milisuthando Bongela: We all had a collective experience of being the first generation of Black kids to go to these white schools and I was trying to validate my own experience, which I’ve never really seen reflected in popular culture and discourse. There were all these tiny cuts that were made every day on our personhood.

It was a process that began in 2016 – I decided to sit down and do these interviews with about 10 of my friends. I touched on every subject I could think of, from very small things … I would show them a space case (pencil case), for instance, and say, what comes to mind? And then the question of class and of our parents struggling to afford the stationery – and what it meant to have, like, the crappy Faber Castell crayons versus the Colleens crayons – and about your academic ability and your intelligence, and all the stuff that’s laden inside. All these stories about bodies, about the ability of black people to engage water, about hair, about the ashiness of our skin, about Vaseline. About all these things that suddenly come up: taxis, transport, the school bell, Afrikaans, kissing! I interviewed them two by two, so that each person would have somebody that’s listening to them and co-conspiring.

The only way out of making sure that my grandkids are not dealing with this in the same way that I’m dealing with it is: we have to figure out how to talk to each other. This is not going to be solved by white people sitting alone together or by black people sitting alone together.

It goes down to the true meaning of (the African philosophy of) ubuntu – which is that we fathom ourselves through each other.

Julia Cain: What would you like to leave with your audiences?

Milisuthando Bongela: The thing I want to leave the audience with is the thing that I’m constantly left with, which is thank God I exist and that I’m born at this time. The world right now … it does feel like we are in free fall, because we are. I have to engage in white supremacy and capitalism and patriarchy. I can’t take it down without understanding it. The way that the world has been, all those ideas have to die. It’s no longer serving humanity. It’s not even serving the people who created it.

We are in the next phase, where what’s required is people who understand the feminine modalities of doing things, and the feminine in men and women, and the multiple expressions of gender that exist. Queer people, trans people, Black people, people of colour all over the world, indigenous peoples – our wisdom, our knowledge, our ways of seeing the world, our sciences – this energy has been suppressed for a long time, and it’s ready to rise and to reconstruct the world.

For me, I’ve learned in the last couple of years that the antidote to fascism is intimacy.

Milisuthando opens the Encounters South African International Documentary Festival on 22 June.

Julia Cain does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.