EITHER that wallpaper goes, or I do.

Such sarcasm. These dying words were supposedly the last spoken by flamboyant Irish poet and playwright, novelist and wit Oscar Wilde on his deathbed in a shabby Parisian hotel room in November 1900.

His full quote begins with Wilde declaring: "The wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death". But is it just possible it wasn't a mere fashion statement from the snobby, sophisticated dramatist?

Maybe Wilde knew full well the danger of wallpaper back then and was simply stating the bloomin' obvious as he drew his last breath. Maybe.

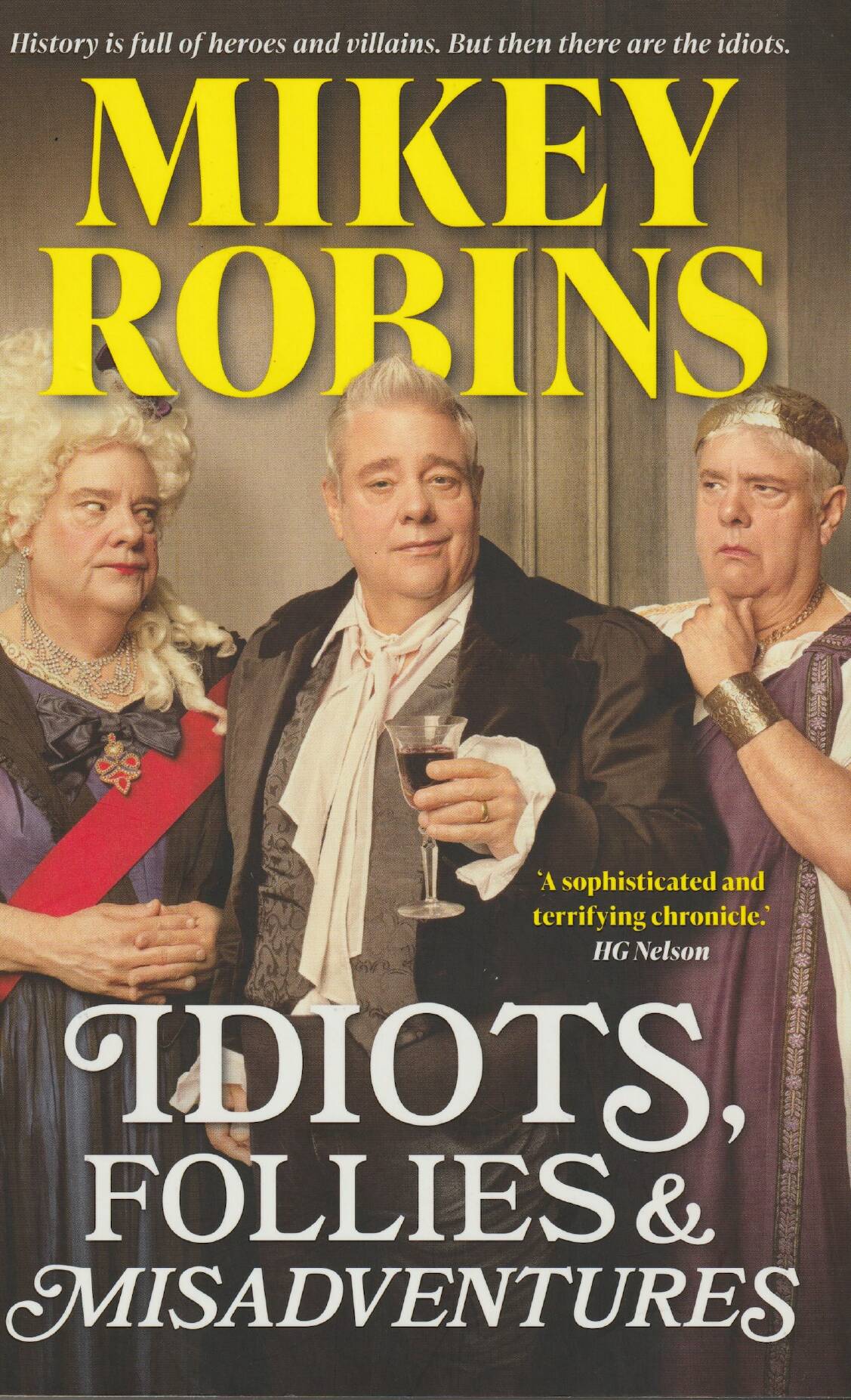

Larrikin comedian and former Novocastrian Mikey Robins reveals all in his new, highly entertaining romp through history, aptly titled, Idiots, Follies and Misadventures (Simon & Schuster, $34.99).

While exploring stupidity through the ages, his chapter called 'Death by wallpaper' explains how there was a chance trendy Victorian-era wallpaper really was trying to kill you.

The weapon was arsenic and 19th century England was awash with the deadly poison.

Not surprisingly, he writes, arsenic was also even considered, in mild doses, to be something of an aphrodisiac. But you wouldn't have to go around licking the wallpaper to get sick, or high. Under damp weather conditions, wallpaper of that era would release both flakes of arsenic or arsenic-laden gas.

And when the exiled French emperor Napoleon died aged only 51 on the remote, damp South Atlantic island of St Helena in 1821, it wasn't long before toxic wallpaper (not stomach cancer) was suspected to be the culprit. That was especially so after his body was exhumed in 1840 to be sent back to France and people were amazed how little the dead emperor had decomposed. His remains were a prime example of "arsenic mumification".

A 20th century test on a souvenired strand of his hair also proved positive for arsenic. So did a similar souvenired scrap of his deathbed wallpaper.

According to Robins' research, arsenic could be found in Victorian-era "beer, wine, sweets, wrapping paper, sheep dip (not unexpected, really), insecticides, clothing, hat ornaments, coal and candles". It was everywhere. Mid-19th century Birmingham doctor William Hines once condemned the reliance on arsenic, warning: "A great deal of slow poisoning is going on in Great Britain".

Further stupidity only compounded the danger. Take the case of sweets-maker William Hardaker, aka Humbug Billy, who confused his stash of arsenic for sugar while whipping up a batch of peppermint candles in 1858. He killed 25 people and poisoned more than 100 others.

Robins, a former member of the Hunter Valley's legendary Castanet Club, went on to become one of Australia's best-known comedians and broadcasters. For seven years, he hosted Triple J's national breakfast show, appeared on TV and has now turned his considerable talents into print, writing for newspapers and magazines and earlier co-authoring two books.

His latest paperback works on the adage that history is full of heroes and villains, but then there are ridiculous idiots, who often are as interesting and intriguing.

Ploughing through the quirky byways of history Robins has uncovered a host of knuckleheads for our reading pleasure. Among the forgotten moments of madness he writes about are the 1826 Christmas eggnog riot, why you shouldn't soak your underpants in mercury, the 'inventor' whose dog toy patent very closely resembled a stick, and the US parents of eight-month-old Jimmy Beagle who sent him via parcel-post to his grandparents' house across town in 1913 to save money.

Then there was the terrifying rumour spread (and widely believed) of bananas carrying flesh-eating germs only in January 2000.

And how about the strange story involving popular author Dr Seuss and his bestselling World War II book, The Pocket Book of Boners. It sold more than one million copies, mainly to American servicemen. It's in the chapter called 'The Cat in the Hat cracked a fat, how 'bout that?'. (For the record, in the early part of the 20th century, boners actually meant a stupid error often associated with a dull-witted person).

Robins is appearing (in conversation with Dan Cox) at the Warners Bay Theatre on Saturday, September 9, as part of Lake Macquarie's History Illuminated series.

While discussing the lighter view of history to his audience, I hope Robins includes my favourite yarn from his book. That concerns the infamous April Fool's Day joke played by the venerable BBC on a gullible British public on April 1, 1957. Its 'Swiss Spaghetti Harvest' segment duped thousands.

The program told of a bumper crop forecast for the vast hillside spaghetti plantations. Indeed, local women were already 'harvesting' cooked, uniform-size strands of pasta from trees because of the mild winter. There was a later disclaimer, but many people must have missed it. The BBC phones rang hot, some from irritated TV watchers that such a factual program would air such a 'flippant piece of tomfoolery".

Other callers asked how they could buy, or even grow a spaghetti bush at home. Frustrated BBC switchboard operators soon settled on the simple response: "Place a sprig of spaghetti in a tin of tomato sauce and hope for the best".

BULLET TO PONDER

WHEN Bob Gulliver's friend supplied him with a small timber paperweight a few months ago, he didn't think he'd have a puzzle to ponder.

A close examination of the lacquered slab of wood seemed to hint at an inner mystery.

Was there something small and round buried within it?

Yes, there was.

Gulliver, of Newcastle, is interested all sorts of timbers and appreciates their colour and beauty.

His gift came from outback NSW, from Lightning Ridge, and had once been part of a tough old fencepost bound for the firepit until rescued.

Gulliver's new curiosity piece was a very hard and heavy Australian wood found in semi-arid areas of most states.

Cleaned up, it had a rich brown colour with a narrow band of yellow sapwood, confirming it was gidgee (or acacia cambagei), classified as the third hardest timber in the world.

As such, gidgee is popularly made into bowls and paper knives.

Gulliver gingerly dug into one side of his new item and discovered a bullet embedded within it.

He made inquiries with a shooters' magazine who told him the almost hidden bullet seemed likely to have come from a .32 calibre police revolver.

"The general view was that the bullet probably lodged in the fencepost during target practice ages ago," Gulliver says.

Weekender then sought the opinion of 'Geoff', a retired Newcastle police detective, who was damning of the old .32 police issue revolver.

"No wonder it was replaced," Geoff said.

"Stopping a criminal with it was hopeless.

"You'd do more harm by throwing it at someone coming at you, hoping to stop him that way," Geoff said.

- Pictured left: Bob Gulliver, of Newcastle, with his small hardwood desktop gift with the mystery object within. Picture by Mike Scanlon

- For more information about Lake Macquarie's History Illuminated festival, which will be held at various venues on September 1-10, visit library.lakemac.com.au