US law enforcement officials arrested two of Mexico’s most wanted kingpins in El Paso, Texas, on July 25 without firing a shot. The two men, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada and Joaquín Guzmán, helped lead arguably the world’s most powerful drug-trafficking organisation: the Sinaloa cartel. The arrest was one of the biggest in nearly two decades of war against Mexico’s drug cartels.

Guzmán, who is one of the sons of Mexican former drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera, led one of the cartel’s factions. But Zambada was the big catch. Now 76 years old, he is one of the last old-school cartel leaders, and has been hunted for decades.

Along with El Chapo, Zambada was one of the co-founders of the Sinaloa cartel in the late 1980s. While the cartel has decentralised into several loosely connected factions over the past decade, Zambada has remained a kingmaker or godfather for the network, brokering deals among the factions and with other cartels.

He is called the capo de capos – the boss of the bosses. And the US$15 million (£11.7 million) US government bounty for his arrest is higher than what the US is offering for any other Mexican cartel leader. The most prominent remaining cartel leader, El Nemesio “El Mencho” Oseguera Cervantes of the Jalisco New Generation cartel, has a US$10 million bounty.

The Sinaloa cartel is one of the largest and oldest drug-trafficking organisations in Mexico. The group traffics drugs globally and, according to the US Drug Enforcement Agency, is “largely responsible” for the flow of fentanyl into the US. The agency says nearly 200 Americans are dying each day from fentanyl overdoses.

Elements of the Mexican government have long been accused of favouritism toward the Sinaloa cartel. In 2023, the former secretary of public security in Mexico, Genaro García Luna, was sentenced to a minimum of 20 years in prison after having been convicted of receiving millions in US dollars of bribes from the cartel.

But even if Mexican officials had made serious efforts to capture Zambada, a successful arrest would have been difficult to pull off. He was notoriously recluse, living in an isolated area where local officials were probably on his side and lookouts warning him of any danger.

And if he would have been arrested in Mexico, he could also have escaped from a Mexican prison. His old partner, El Chapo, did so twice.

A one-of-a-kind arrest

Given this slippery situation, US authorities needed to engineer a clever plan to arrest Zambada. US officials are generally not permitted to carry weapons in Mexico, and security cooperation between the US and Mexico is at a low point.

Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, is a leftist populist leader who has touted his independence from the US. According to Vanda Felbab-Brown, an analyst at Brookings Institution, López Obrador’s tenure has left the security relationship between the two countries in a “deep freeze”.

To arrest Zambada, then, the US had to get him to cross the border. The exact details of the scheme are still unknown, but the Wall Street Journal is reporting that Guzmán tricked Zambada by getting him to board a plane that was supposedly going to inspect clandestine airstrips in northern Mexico.

But when the plane landed at a small airport near El Paso, US federal agents were waiting and arrested both Guzmán and Zambada. Guzmán probably facilitated the transport of Zambada as part of a deal to lessen his own sentence.

Zambada pleaded not guilty to charges of drug trafficking and money laundering at a court in El Paso on Friday. However, with two of the top Sinaloa cartel leaders now almost certainly heading for prison, the cartel’s future remains unclear.

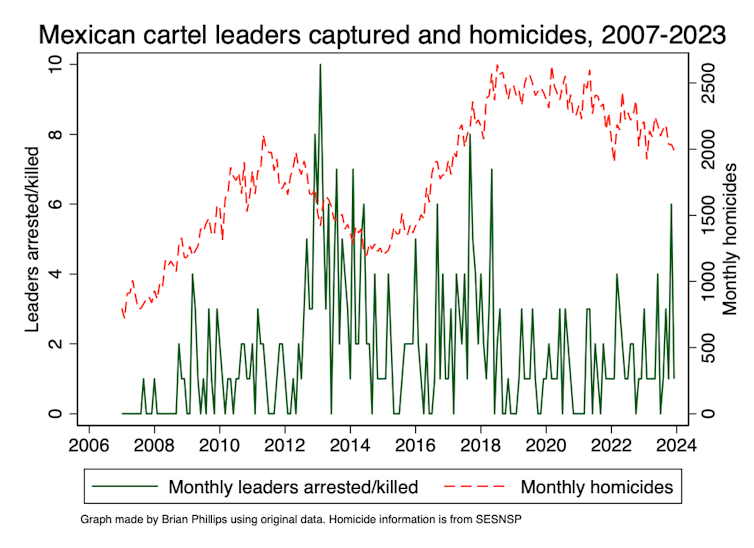

In the short term, at least, there could be increased violence. Past leadership captures have usually led to fights among factions over leadership succession, as my own research from 2015 has shown.

They have also emboldened rival groups to attack. Competitors like the Jalisco New Generation cartel could seize the opportunity to move in on Sinaloa’s market. The Jalisco group did exactly this after the arrest of El Chapo in 2017, gaining territory.

Life may get complicated for Mexicans living in areas influenced by the Sinaloa cartel, mainly in the north and west of the country. The Mexican government has already sent soldiers to the city of Culiacán anticipating a surge of violence.

One possible bright side is that Mexican officials were apparently not involved in the capture. This means retaliatory violence against the Mexican government or the wider public is unlikely – as happened in 2023 when another son of El Chapo was arrested. These events may explain why Mexico did not carry out the arrest this time, or at least why it has not revealed any participation in the US operation.

Do the arrests mean the end of the Sinaloa cartel? Hardly. The group’s global drug business has a solid infrastructure in place, and it does not depend on one or two men.

The group may weaken, especially if rival groups take advantage of the situation. But the cartel has survived for more than 30 years by adapting to many changing circumstances, and it’s likely to survive this one as well.

Furthermore, as my data shows, hundreds of cartel leaders have been arrested or killed over the years, yet violence remains much higher than it was in 2007 when Mexico’s “war on drugs” began.

The Mexican government, working with the US, will need to use other approaches to defeat the cartels. These include fighting widespread corruption and addressing the massive demand for drugs like fentanyl in the US.

Brian J. Phillips does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.