Planetary scientists have discovered salty glaciers near the north pole of Mercury, raising the possibility that the closest planet to the sun may be capable of hosting life. The new findings, which were made using past observations from NASA's retired MESSENGER probe, were published in The Planetary Science Journal in November.

"Our finding complements other recent research showing that Pluto has nitrogen glaciers, implying that the glaciation phenomenon extends from the hottest to the coldest confines within our Solar System," lead study author Alexis Rodriguez, a planetary scientist at the Arizona-based nonprofit Planetary Science Institute (PSI), said in a statement.

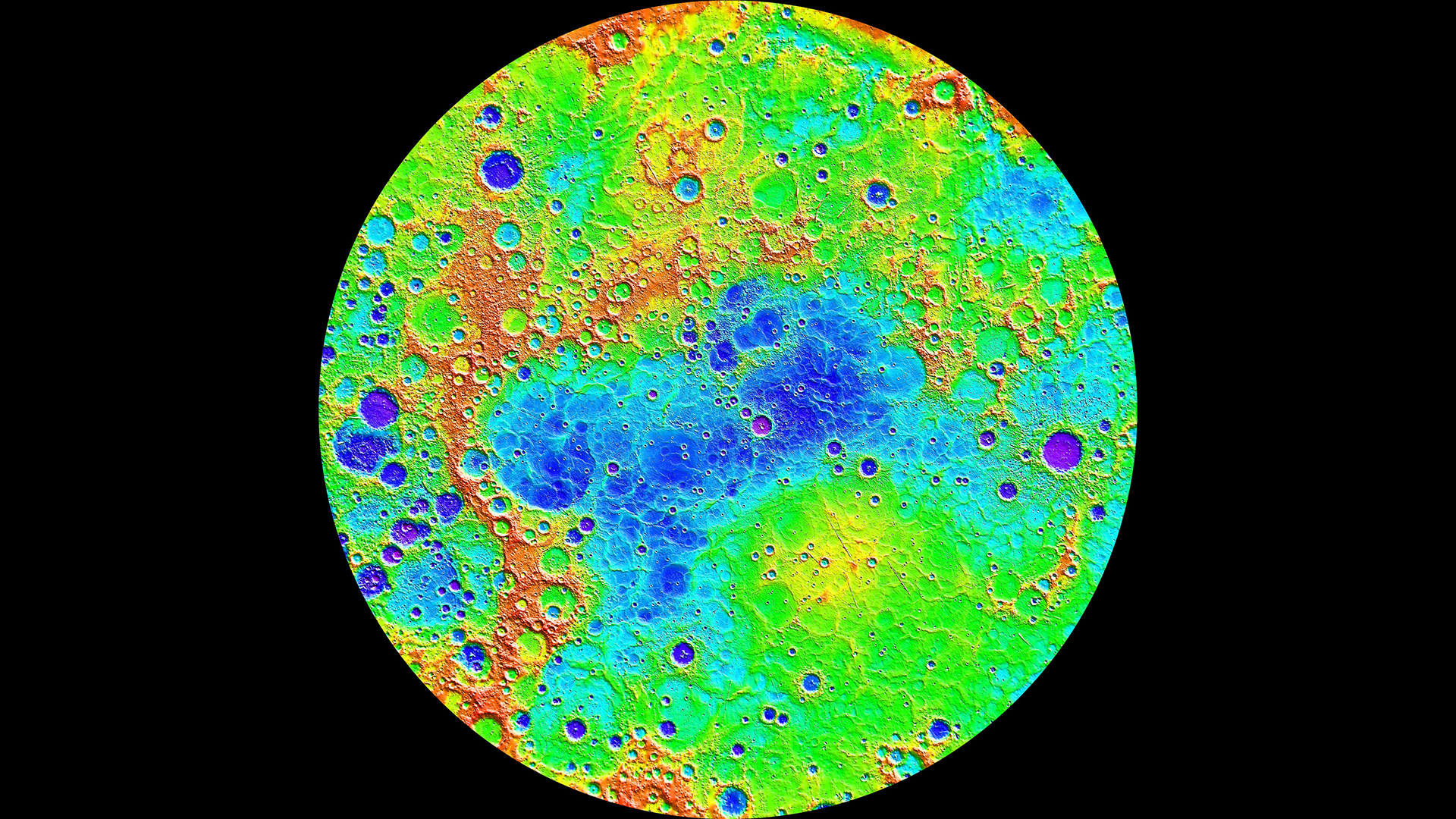

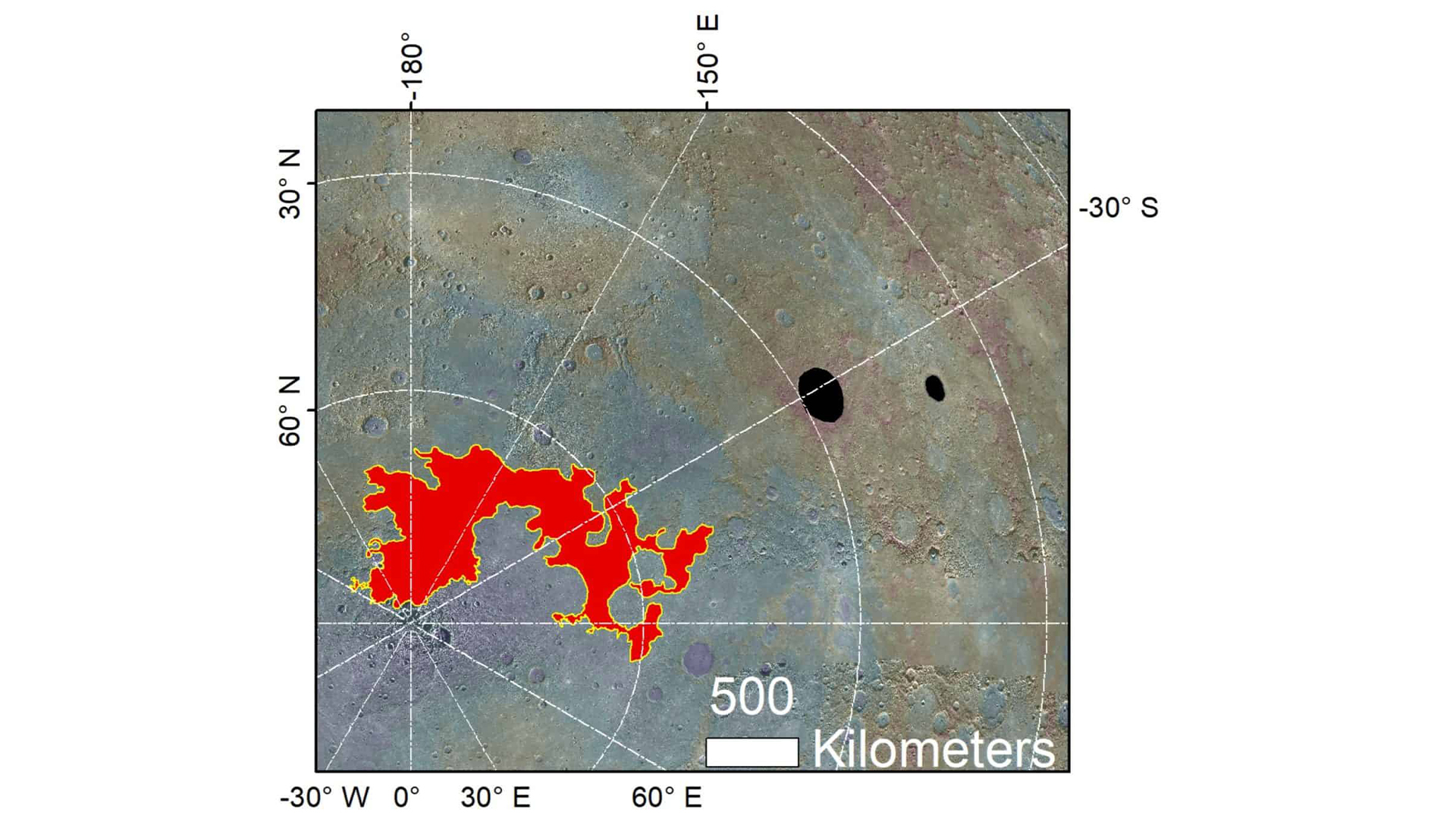

These glaciers, found in Mercury's Raditladi and Eminescu craters, aren't quite like the typical icebergs we think of on Earth. Instead, they're flows of salt that trapped volatile compounds deep below Mercury's surface. In geology terms, volatiles are chemicals that readily evaporate on a planet — like water, carbon dioxide and nitrogen. Mercury's strange salt-bergs were revealed by asteroid impacts, which exposed this material trapped below the surface; that's why scientists discovered them in craters.

Glaciers are surprising to find on Mercury because of its proximity to the sun; the planet is 2.5 times closer to our star than Earth is. At that small distance, things are a lot hotter. Yet, these salt flows could have preserved their volatiles for "over one billion years," according to study co-author Bryan Travis, also a planetary scientist at PSI.

Although Mercury's salty deposits aren't analogous to typical icebergs or Arctic glaciers, similarly salty environments do exist on Earth, so geologists have a good idea of what these environments are like — and whether life can emerge there.

"Specific salt compounds on Earth create habitable niches even in some of the harshest environments where they occur, such as the arid Atacama Desert in Chile," Rodriguez said. "This line of thinking leads us to ponder the possibility of subsurface areas on Mercury that might be more hospitable than its harsh surface."

With volatiles — which are necessary for life, especially water — trapped underground, Mercury might be able to sustain subterranean life sheltered from the harsh rays of the sun. Just as planetary systems have "Goldilocks zones" — regions around their star where liquid water can persist — might have a similar "potentially habitable" region below its surface, the researchers suggested. And if Mercury could host life, then exoplanets similar to Mercury might become more enticing to scientists who are hunting for alien life.

The discovery of these glaciers also helps to explain a long-standing mystery about Mercury: craters with chunks missing. The researchers propose that the little pits observed dotting some craters used to be filled with volatiles, before the impact exposed them and they evaporated.

One big question remains: How did the volatile layers get there in the first place? Observations of Mercury's north pole suggest the volatiles were deposited on top of a fully formed landscape. Rodriguez suggested they could come from "the collapse of a fleeting, hot primordial atmosphere early in Mercury's history."

Alternatively, maybe Mercury had lakes, co-author Jeffrey Kargel, also at PSI, proposed. Perhaps "a dense, highly salty steam" leaked out of the volcanic interior of young Mercury and then evaporated, leaving the salt behind, he said.

Further studies are needed to truly shine a light on what may lurk below Mercury's surface.