The story so far: Mental disorders are a major cause of disability worldwide, largely due to insufficient understanding, pervasive ignorance, and social stigma. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one out of every eight people globally is affected by a mental disorder. India significantly contributes to this global burden.

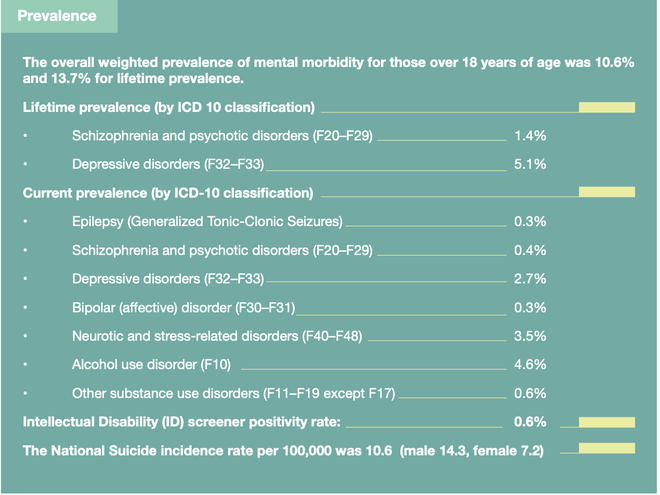

The National Mental Health Survey (NMHS) of 2015-2016 highlights the huge burden of mental health problems in India. As per the findings of the report, 150 million adults live with a mental disorder and require access to care services, but the majority are unable to access treatment.

Another study published in Lancet Psychiatry reveals that the proportional contribution of mental disorders to the total disease burden in the country doubled between 1990 and 2017. It estimated that one in seven Indians (197 million) were suffering from mental disorders of varying severity, with depression and anxiety disorders the most common. The treatment gap for mental disorders was found to be as high as 83%.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the crisis, severely affecting the psycho-social well-being of many. Noting the increasing burden, a recent Standing Committee report tabled in Parliament highlighted that the high treatment gap for most illnesses was due to a lack of mental health professionals, poor infrastructure and stigma. The panel suggested the government strengthen mental health facilities at primary and secondary levels to improve overall availability and accessibility of mental healthcare for all.

(For the top health news of the moment, subscribe to our newsletter Health Matters)

What is mental health?

Similar to physical health, mental health is a crucial component of overall health encompassing the psychological, emotional and social well-being of an individual. The WHO defines mental health as a state of well-being in which a person realises their abilities, copes with the normal stresses of life, works productively and makes a contribution to the community. It extends to a positive state of mental and emotional well-being. When there is a significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotional regulation, or behaviour, usually associated with distress or impairment, it is referred to as a mental health disorder.

While globally there is a significant number of individuals who need mental healthcare, far fewer actually receive treatment, even if effective treatments are available at a low cost. Most don’t have access to care services, adding to the widening gap between those who need care and those with access to such care. For instance, only 29% of people with psychosis and only one-third of people with depression receive formal mental healthcare worldwide. In India, all mental disorders, except epilepsy, recorded a treatment gap of more than 60%, with the highest being for alcohol use disorders at a shocking 86%.

What is the government doing to tackle mental illnesses?

The policy landscape around mental health has evolved over the years, driven mainly by the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP), aimed at providing affordable and accessible mental healthcare facilities. India was one of the first few developing countries that took the lead in developing a national programme in 1982 to address the mental health needs of its population by integrating mental health services with general care available at primary health centres. As part of the programme, primary and community health workers were given specialised training for the treatment of mental disorders.

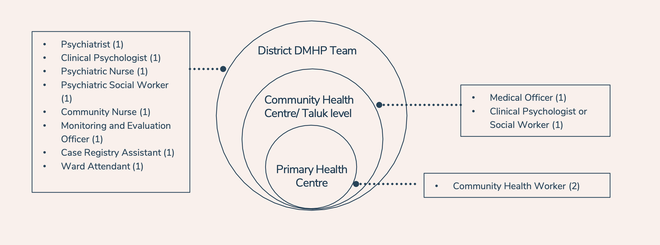

The NMHP was re-strategised as the District Mental Health Programme (DMHP) to decentralise care. Districts were designated as the main administering units for the implementation of the programme. The DMHP aimed to provide mental health services, which included managing cases, counselling, manpower training and spreading awareness, at different levels of the district healthcare delivery system. It was later integrated with the National Rural Health Mission.

Currently, the National Mental Health Programme is active in 743 districts across 36 States and Union Territories. The facilities offered at community and primary health centre levels include outpatient services, assessments, counselling, psycho-social interventions, continuing care and support for people with severe mental disorders, medications, outreach services, and ambulance services.

Meanwhile, in response to the growing burden of mental illness, the government launched India’s first national mental health policy in 2014. It calls for a more accessible and holistic treatment of mental illnesses and advocates for the decriminalisation of attempted suicide. Another programme, Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK), was also launched in the same year under the National Health Mission to focus specifically on adolescent health.

Another “watershed moment for the right to health movement in India” arrived in the form of the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017. It discourages the long-term institutionalisation of patients and reaffirms the right of people to live independently and within communities. It places a range of duties on mental health professionals, the state and other duty-bearers to protect the autonomy and dignity of persons with mental illness.

Besides the national programme, mental health services are provided as part of services under the Comprehensive Primary Health Care under Ayushman Bharat – Health and Wellness Centre scheme. The government has also released operational guidelines on mental, neurological and substance use disorders at health and wellness centres (HWC) under the ambit of Ayushman Bharat.

Last year, the National Tele-Mental Health Programme (NTMHP) was launched under the NMHP to use digital technology to address growing mental health challenges and improve access to quality mental health counselling and care services in the country.

What has the experience been so far?

The mental health programme has been credited for enhancing the reach of mental health services at the community level but is also criticised for its ineffective design and functioning. There is a consensus among experts that its impact has been limited, mainly because of a lack of trained health workers, financial constraints and poor coordination. The DMHP can be simultaneously narrated as “a heroic struggle against overwhelming odds” as well as that of “abject failure”, says an article published in the Economic and Political Weekly.

“Financial and human capital restrictions, a lack of public involvement, inefficient training, poor non-governmental organisation/private cooperation, and a deficit of solid monitoring and evaluation system have all hampered the programme’s impact,” argue the authors of an article in the Cureus Journal of Medical Science. Another paper on India’s response to mental healthcare argues that the model was deficient, being focused on pharmacological interventions and not including the psychosocial aspects of treatment.

“It excluded community/stakeholder participation in the planning and implementation process that further attributed to its poor performance,” it adds, concluding that the implementation of the programme at the sub-district level and below is presently sub-optimal.

As far as the Centre’s digital reach is concerned, the national tele-mental health helpline, called Tele-MANAS, has recorded over 3.5 lakh calls since its launch in 2022. As of October, 44 Tele-MANAS cells are spread across 32 States and UTs, with 2,000 professionals taking around 1,000 calls per day in 20 languages on average.

Despite the growing response, the helpline faces several challenges. Research has shown that individuals with mental health issues, who require care, often do not have access to the Internet or smartphones. Besides barriers related to digital literacy, data privacy issues flagged by a response by the helpline nodal centre NIMHANS to an RTI query have added to concerns. Implementation of the RKSK, meanwhile, has been unsatisfactory despite being in operation for nearly a decade.

How accessible and affordable is mental healthcare?

According to a report presented by the Standing Committee in Parliament in August, India has only 0.75 psychiatrists per lakh people. This is a much lower number than that required to address the growing mental health problems in the population. The panel has suggested that an additional 27,000 psychiatrists are necessary to achieve the target of having three psychiatrists per lakh people. The report also highlights that this shortage is prevalent for other health professionals such as psychologists, psychiatric social workers and nurses.

In 2018, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) told the Lok Sabha that there are only 898 clinical psychologists against a demand of 20,250, and 1,500 psychiatric nurses compared to a demand of 30,000. An analysis and cost implementation of the mental health policy in the same year, however, noted that India had nearly 9,000 psychiatrists, 2,000 psychiatric nurses, 1,000 clinical psychologists, and 1,000 psychiatric social workers for its population of 1.3 billion— a population that includes approximately 150 million who need intervention for mental disorders.

The paper published in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry further noted that India would need an additional 30,000 psychiatrists, 37,000 psychiatric nurses, 38,000 psychiatric social workers and 38,000 clinical psychologists. “… it will take 42 years to meet the requirement for psychiatrists, 74 years for psychiatric nurses, 76 years for the psychiatric social worker, and 76 years for clinical psychologists, for providing care for 130 crore population, provided the population (assuming both general population and mental health human resources) remains constant,” the researchers concluded.

The study also reviewed the status of infrastructure in hospitals. It found that around 56,600 public psychiatric beds existed for 130 crore people. This included 35,000 psychiatric beds in mental hospitals, 10 beds each in 723 district hospitals and 30 beds each in 479 medical colleges. It estimated that there was a requirement of 6.5 lakh psychiatric beds for a 130 crore population.

Besides the gap in implementation, experts have identified poverty and discrimination as key contributors to the treatment gap; affordability remains a major factor in availing treatment. A recent study published in the Indian Journal of Health Management found that spending on mental disorders pushed around 20% of Indian families into poverty.

A household spends over 18.1% of their total budget per month on the care of a member with a mental disorder, it found. Even though mental healthcare in government-run hospitals and health centres is subsidised, a long course of treatment means high travelling expenses. Multiple visits to health professionals, and cost and unavailability of medication add to the financial burden. “There is a critical need to provide financial risk protection to reduce financial impact of healthcare expenditure on mental illness among households in India,” the authors noted.

In urban areas, therapists usually charge Rs 500-2,000 for each session that lasts less than an hour on average. This means that an individual could end up spending around Rs 4,000-Rs 8,000 a month on therapy, which is likely to affect their spending and savings. The high cost of the therapy and other logistical costs force several to quit treatment. A person who took therapy at a private centre in Chandigarh tells The Hindu, “I took two sessions, but didn’t return for a third because the cost of therapy and other expenses badly hit my monthly budget.”