Reactions came quickly to the federal indictment on Sept. 22, 2023, of New Jersey’s senior U.S. senator, Democrat Bob Menendez. New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy joined other state Democrats in urging Menendez to resign, saying, “The alleged facts are so serious that they compromise the ability of Senator Menendez to effectively represent the people of our state.”

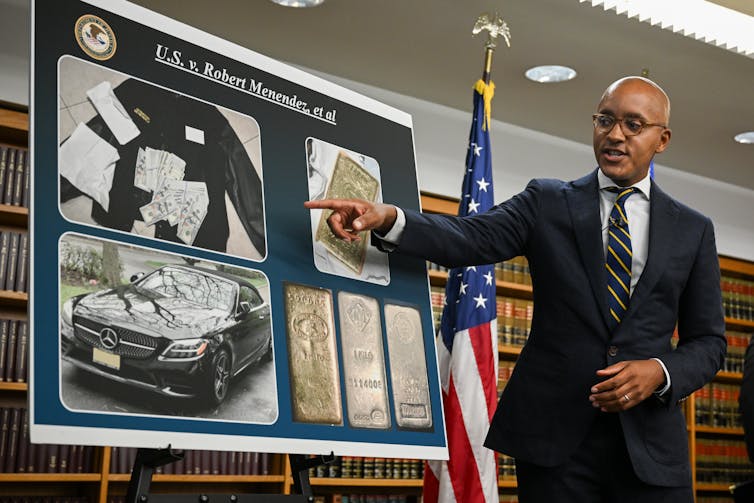

The indictment charged Menendez, “his wife NADINE MENENDEZ, a/k/a ‘Nadine Arslanian,’ and three New Jersey businessmen, WAEL HANA, a/k/a ‘Will Hana,’ JOSE URIBE, and FRED DAIBES, with participating in a years-long bribery scheme … in exchange for MENENDEZ’s agreement to use his official position to protect and enrich them and to benefit the Government of Egypt.” Menendez said he believed the case would be “successfully resolved once all of the facts are presented,” but he stepped down temporarily as chairman of the Senate’s influential Committee on Foreign Relations.

The Conversation’s senior politics and democracy editor, Naomi Schalit, interviewed longtime Washington lawyer and Penn State Dickinson Law professor Stanley M. Brand, who has served as general counsel for the House of Representatives and is a prominent white-collar defense attorney, and asked him to explain the indictment – and the outlook for Menendez both legally and politically.

What did you think when you first read this indictment?

As an old pal once told me, “even a thin pancake has two sides.”

Reading the criminal indictment in a case for the first time often produces a startled reaction to the government’s case. But as my over 40 years of experience defending public corruption cases and teaching criminal law have taught me, there are usually issues presented by an indictment that can be challenged by the defense.

In addition, as judges routinely instruct juries in these cases, the indictment is not evidence and the jury may not rely on it to draw any conclusions.

The average reader will look at the indictment and say, “These guys are toast.” But are there ways Menendez can defend himself?

There are a number of complex issues presented by these charges that could be argued by the defense in court.

First, while the indictment charges a conspiracy to commit bribery, it does not charge the substantive crime of bribery itself. This may suggest that the government lacks what it believes is direct evidence of a quid pro quo – “this for that” – between Menendez and the alleged bribers.

There is evidence of conversations and texts that coyly and perhaps purposely avoid explicit acknowledgment of a corrupt agreement – for instance, “On or about January 24, 2022, DAIBES’s Driver exchanged two brief calls with NADINE MENENDEZ. NADINE MENENDEZ then texted DAIBES, writing, ‘Thank you. Christmas in January.’”

The government will argue that this reflects acknowledgment of a connection between official action and delivery of cash to Sen. Menendez, even though it is a less-than-express statement of the connection.

Speaking in this kind of code may not fully absolve the defendants, but the government must prove the defendants’ intent to carry out a corrupt agreement beyond a reasonable doubt – and juries sometimes want to see more than innuendo before convicting.

The government has also charged a crime called “honest services fraud” – essentially, a crime involving a public official putting their own financial interest above the public interest in their otherwise honest and faithful performance of their duties.

The alleged failure of Menendez to list the gifts, as required, on his Senate financial disclosure forms will be cited by prosecutors as evidence of “consciousness of guilt” – an attempt to conceal the transactions.

However, under a recent Supreme Court case involving former Gov. Bob McDonnell of Virginia for similar crimes, the definition of “official acts” under the bribery statute has been narrowly defined to mean only formal decisions or proceedings. That definition does not include less-formal actions like those performed by Menendez, such as meetings with Egyptian military officials.

The Supreme Court rejected an interpretation of official acts that included arranging meetings with state officials and hosting events at the governor’s mansion, or promoting a private businessman’s products at such events.

When it comes time for the judge to instruct the jury at the end of the trial, Menendez may well be able to argue that much of what he did in fact did not constitute “official acts” and therefore are not illegal under the bribery statute.

This case involves alleged favors done for a foreign country in exchange for money. Does that change this case from simple bribery to something more serious?

The issue of foreign military sales to Egypt may also present a constitutional obstacle to the government.

The indictment specifically cites Menendez’s role as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and actions he took in that role in releasing holds on certain military sales to Egypt and letters to his colleagues on that issue. The Constitution’s speech or debate clause protects members from liability or questioning when undertaking actions within the “legitimate legislative sphere” – which undoubtedly includes these functions.

While this will not likely be a defense to all the allegations, it could require paring the allegations related to this conduct. That would whittle away at a pillar of the government’s attempt to show Menendez had committed abuse of office.

In fact, when the government has charged members of Congress with various forms of corruption, courts have rejected any reference to their membership on congressional committees as evidence against them.

How likely is Menendez’s ouster from the Senate?

Generally, neither the House nor Senate will move to expel an indicted member before conviction.

There have been rare exceptions, such as when Sen. Harrison “Pete” Williams was indicted in the FBI Abscam sting operation from the late 1970s and early 1980s against members of Congress. Williams resigned in 1982 shortly before an expected expulsion vote. With current Democratic control of the Senate by a margin of just one seat, Menendez’s ouster seems unlikely even though the Democratic governor of New Jersey would assuredly appoint a Democrat to fill the vacancy.

‘In the history of the United States Congress, it is doubtful there has ever been a corruption allegation of this depth and seriousness,’ former New Jersey Sen. Robert Torricelli said. True?

That seems hyperbolic. The Menendez case is just the latest in a long line of corruption cases involving members of Congress.

In the Abscam case, seven members of the House and one Senator were all convicted in a bribery scheme. That scheme involved undercover FBI agents dressed up as wealthy Arabs offering cash to Congress members in return for a variety of political favors.

In the Korean Influence Investigation in 1978 – when I served as House counsel – the House and Department of Justice conducted an extensive investigation of influence peddling by Tongsun Park, a South Korean national, in which questionnaires were sent to every member of the House relating to acceptance of gifts from Park.

Going all the way back to 1872, there was the Credit Mobilier scandal that involved prominent members of the House and Vice President Schuyler Colfax in a scheme to reward these government officials with shares in the transcontinental railroad company in exchange for their support of funding for the project.

Stanley M. Brand does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.