“Angels don’t speak English, they speak emotion,” Edgar, a gaunt 24-year-old, tells Ryann Billitteri as she approaches him outside the Taco Bell at Dearborn and Van Buren Wednesday afternoon. “The translation is through your life....”

He continues, blending near-poetry and conspiracy theories, wild claims and philosophical riffing, as Billitteri, a caseworker at Thresholds, gently steers him out of the rain and into the restaurant, where she buys him a Taco Supreme (“If you could bless me with extra sour cream on the side,” he says) and tries to get Edgar to sign a form to help him get off the street and into housing. Where he sleeps now, he says, is “classified.”

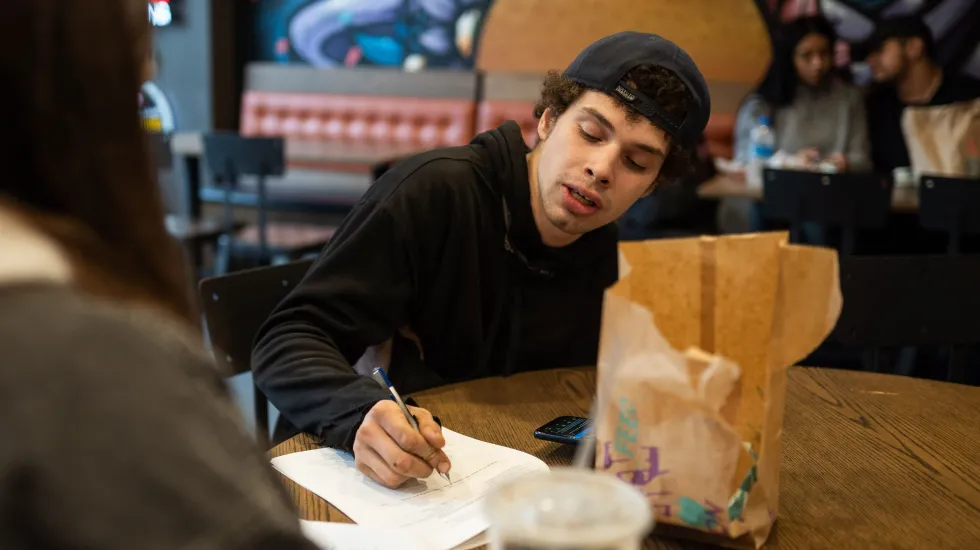

Edgar sits and talks. Billitteri, team lead of Theshold’s homeless outreach program, listens, silently proffering a pen. But he doesn’t sign. She’s been trying for months.

Opinion

Only about a third of Illinoisans who need treatment for mental illness get it; social services in the state are perennially underfunded, trimmed to the bone after years of sweeping budget cuts.

“Since time immemorial,” said Heather O’Donnell, senior vice president of public policy and advocacy at Thresholds, which provides a range of mental health, addiction and housing support for the disadvantaged, plus guiding the formerly incarcerated as they transition back into society. “This has been happening for decades; it’s just snowballing because of the pandemic.”

COVID-19 hit Illinois’ social services hard, further decimating staffs and budgets. Thresholds, one of the largest providers in the state, had to stop accepting new clients.

“We have basically closed intake,” said Mark Ishaug, CEO of Thresholds. “Thousands of people have been turned away.” It’s the same everywhere.

“People are being told to come back in two months, or we’ll put you on a waiting list,” said Illinois House Majority Leader Rep. Greg Harris (D-Chicago). “It’s a totally unworkable solution. That’s why I got involved.”

Late last year, Harris was lead sponsor of House Bill 4238, the Rebuild Illinois Mental Health Workforce Act. a $140 million shot in the arm that would streamline payment for services. Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s office added it his budget, which needs to be approved by April 8. The bill has 74 co-sponsors, both Democrat and Republican.

“It’s a hugely bipartisan bill,” said Harris. “It’s a universal need.”

Harris said this issue has wide support because mental illness and addiction cut across so many lives, including his own.

“I’ve struggled with mental health and substance abuse for years, and it’s certainly gotten worse during COVID,” Harris said. “It’s a terrible thing to think there are people in far worse circumstances than me who are desperate for access. People want this more than ever. Demand is just skyrocketing. At a time when people need it the most, help is just not available.”

Now between the bill and the budget, the hope is that the bottleneck can be relieved.

“We have the ability to turn this around,” said Ishaug. “We are hopefully going to get this over the finish line, and finally do the right thing.”

Until then, the need surges as resources dwindle. The job remains as hard as ever, with fewer hands to do it.

Jason Grebasch, senior director of access and implementation at Thresholds, said his staff, usually about 30, is down 12 positions.

“It’s very difficult,” he said. “We can’t hire and retain staff. This is very complex, very hard work.”

“We’ve actually had to shrink our services,” said Debbie Pavick, chief clinical officer at Thresholds. That affects “people who have the highest need — those with serious mental illness, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, a long history of incarceration.”

Billitteri once asked Edgar what being schizophrenic feels like. He mentioned those Charlie Brown TV specials, where adults speak in muted trumpet wah-wah garbles. “That’s what I hear all the time,” he said.

Now she listens to him talk. Her job requires patience. It consists of small steps forward and sudden slides back, of clients who need housing but refuse the apartment found for them. Creativity is essential. The Social Security Administration will issue only 10 new social security cards over the lifetime of any individual, a limit quickly reached with homeless persons who can be robbed, lose their paperwork or have possessions thrown away by city workers. But Billitteri has developed work-arounds, like using past medical documentation as proof of a Social Security number.

“It’s my job to figure it out and sometimes I can hardly figure it out,” she says. Figuring it out, at the moment, requires Edgar to sign an HMIS form to get him into the Coordinated Entry System. “We got him an ID; the next goal is permanent housing.”

“Do you mind signing this?” she says. More than once.

“These are the ends times ...” Edgar says. “How come 9/11, we have interviews with firefighters having witnessed demolitions prior to anything? Blew up the Twin Towers. Secret wars. I learned that about Hail the Sun, my favorite band. The music is insane, insane, but the talent is so rare, like a treasure chest, a message in a bottle. As a Christian, you never want to play one of these channels, secular music ...”

After nearly a half hour of this, Edgar takes the pen, and signs.