After decades of development, Francis Ford Coppola’s self-financed film Megalopolis was finally released in cinemas on September 27. It cost the director US$120 million (£91.5 million) and has received overwhelmingly negative reviews, with a global box-office taking of just US$4 million during its opening weekend. This has prompted reports that the film is crumbling, sputtering and a “financial disaster”.

Megalopolis frames the US as the new Roman Empire. On the surface, the film is about what happens when an empire’s decline has reached rock bottom and there is no sense of what comes next – except for a radical, utopian experiment by a young but troubled architect and scientist (Adam Driver), whom the people in power dislike.

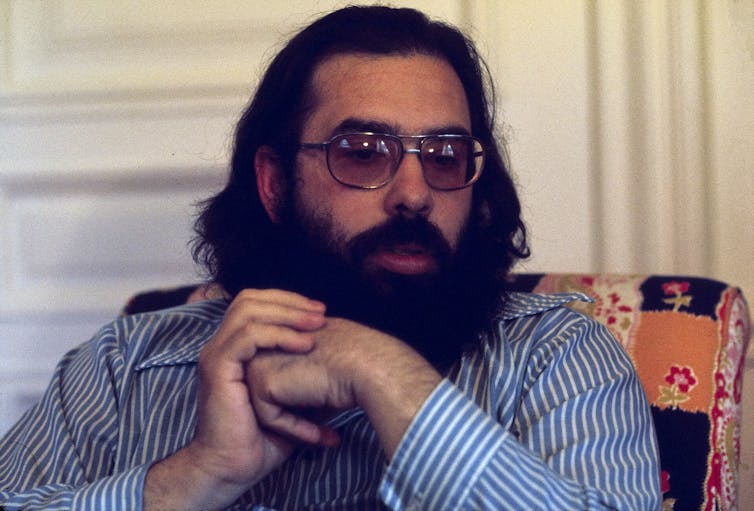

But on a deeper level, and for those familiar with Coppola’s 60-year career, the young, troubled visionary played by Driver looks a lot like the director himself, who over the course of his career has had epic battles with the studios and the conglomerates that have controlled cinema since the 1960s.

Intent on materialising his vision, which was often tied to advancements and experiments in technology that the financiers of his films were not comfortable with, Coppola frequently fought tooth and nail with the establishment.

The end of an empire

The multiple Oscar-winning director has experienced many triumphs (The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, Apocalypse Now) but also crushing failures (One from the Heart, Tucker: A Man and His Dream). His last major film release was The Rainmaker in 1997, while for the past 27 years he has only managed three small films that barely registered (Youth without Youth, Tetro and Twixt).

In this context, Megalopolis is also an allegory for the Coppola family – another empire that seems to be reaching an end. Coppola, the patriarch, is in now in his mid-80s. Even though his children, Sofia and Roman, and nephews, Nicolas Cage and Jason Schwartzman, are all very much established artists in the film industry, they tend to be associated with indie film and genre movies. They have little to do with the grandiose cinematic experiments of the family’s patriarch.

Looking at the film in this way, it can be seen as a messy representation of a family that has been in the limelight for decades, with their triumphs, failures, family tragedies and bankruptcies scrutinised.

Furthermore, a cultural idea of Coppola as a megalomaniac filmmaker whose post-1980 films never lived up to the expectations his 1970s films established has continued to persist. This is despite the fact that Coppola has continually tried to push the envelope in terms of what can be done with cinema, and even what counts as cinema.

Uncompromising vision

Because he decided to self-finance Megalopolis, this time Coppola was completely unrestrained in materialising his vision. Cue a torrent of visuals in support of a story that often does not make sense, as it also doubles up as a re-imagining of his biography.

Add to that a cornucopia of themes, ranging from the state of American politics and how entertainment corrupts it, to efforts to save the empire and “make America great again” – and more than a nod to the rise of fascism. It is not surprising that the film is pulled in so many different directions, turning it into a “hot mess”, as an early review put it.

Reviews from Megalopolis’s opening weekend stuck with this script, using words and phrases such as “epic fail”, “plainly nuts”, “confusing” and “bloated”.

But should a film that does not make money at the box office still be considered a financial disaster, when it was not made under a production model that is based on a corporate entity making a return on its investment? I would argue that a director spending their own money to do what they want – in this case, create a very expensive artwork – seemingly without caring about getting it back, isn’t really a disaster.

Coppola has managed something extraordinary. He made his passion project by any means necessary, and he did it without compromising his vision. He had the film released theatrically on the global market, and had all major news outlets and critics engage with it.

I believe that while the market may have rejected Megalopolis in its theatrical release, it will eventually accept it. The film will find its way to the Blu-ray and streaming markets. It will then be part of retrospectives honouring Coppola. And years down the line, it will be “rediscovered”, with future critics arguing how audiences and the critical establishment in the 2020s were not ready for the film’s visionary take on that era’s culture.

There is no precedent for what Coppola has done, on the scale that he has done it. Discussions of Megalopolis’s “failure” are grounded in conventional film production and circulation. But there is little (if anything) that is conventional about the film and its making.

Perhaps such conventional, market-driven evaluation criteria are not appropriate for a film such as Megalopolis, which, decades down the line, will not be “dead on arrival”, as some reviews put it, but alive and kicking. An example of visionary filmmaking that was misunderstood upon its initial release.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Yannis Tzioumakis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.