Medieval Oxford’s “lethally violent” student population made the city England’s “murder capital”, a new crime map has revealed.

Researchers, including those from the University of Cambridge, mapped medieval England’s known murder cases, adding Oxford and York to its street plan of London’s 14th century slayings.

Oxford’s student population was by far “the most lethally violent” of all groups in any of the three cities, said the analysis, revealed in the digital resource Medieval Murder Maps.

While Oxford in late medieval England was one of the most significant centres of learning in Europe, with a population of around 7,000 inhabitants and “perhaps 1,500 students”, researchers said the city’s homicide rate was around 60-75 per 100,000.

This was 50 times higher than in 21st century English cities.

Crime scenes based on translated investigations from 700-year-old coroners’ inquests were plotted by the researchers.

They estimated the per capita homicide rate in Oxford to be 4-5 times higher than late medieval London or York.

About three-fourths of the Oxford perpetrators with a known background were “clericus” – students or members of the early university – as were nearly 75 per cent of the victims.

“Oxford students were all male and typically aged between fourteen and twenty-one, the peak for violence and risk-taking,” said Manuel Eisner, an investigator who was part of the murder map project.

“These were young men freed from tight controls of family, parish or guild, and thrust into an environment full of weapons, with ample access to alehouses and sex workers,” Mr Eisner said, adding that Oxford at the time had a “deadly mix of conditions”.

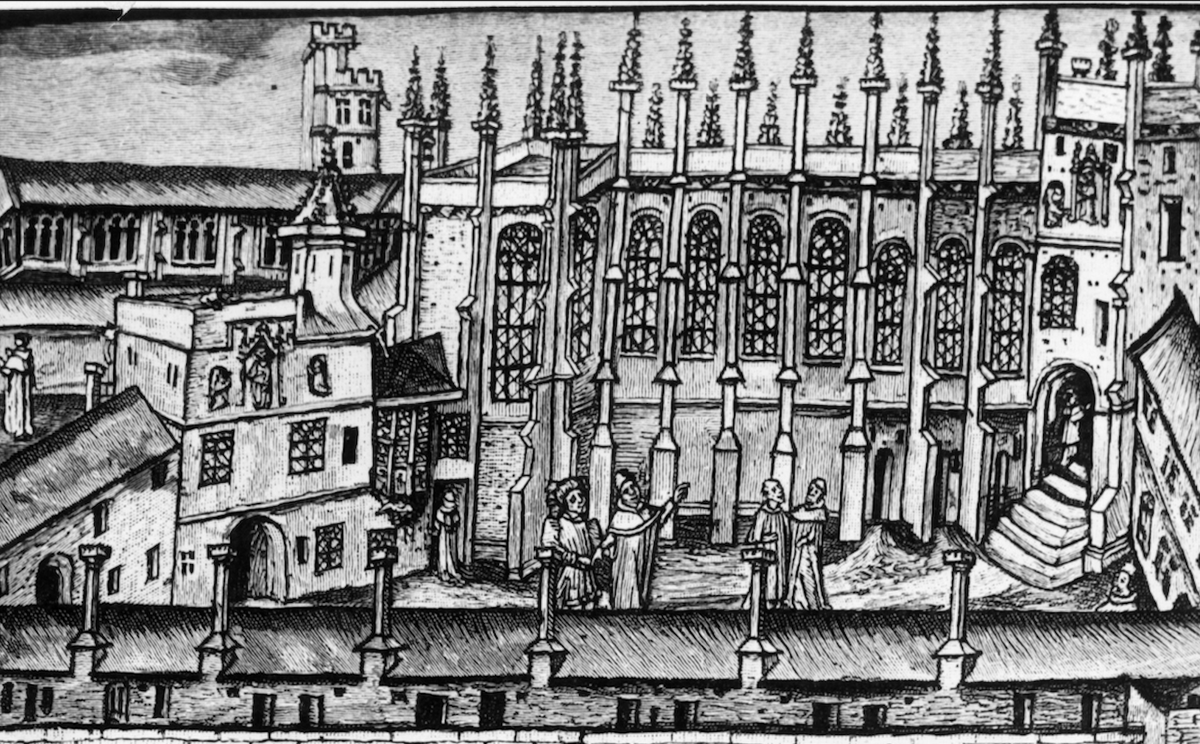

Oxford medieval murder map— (University of Cambridge)

Many students, he said, also belonged to regional fraternities that were found to be an additional source of conflict.

The new interactive map, launched by Cambridge’s Violence Research Centre, allows users to compare the causes and patterns of urban violence in medieval England across three cities.

In the case of York, many of the documented homicides were between artisans in the same profession, from knife fights among tannery workers to fatal violence between glove makers.

The data for the map was from coroners’ rolls, which are catalogues of sudden or suspicious deaths as deduced by a jury of local residents “of good repute”.

“When a suspected murder victim was discovered in late medieval England the coroner would be sought, and the local bailiff would assemble a jury to investigate,” Dr Eisner explained.

The jury’s task was to establish the course of events by hearing witnesses, assessing evidence and then naming a suspect.

“We do not have any evidence to show juries wilfully lied, but many inquests will have been a ‘best guess’ based on available information,” Cambridge historian Stephanie Brown said.

“In many instances, it is likely the jury named the right suspect, in others it may be a case of two plus two equals five,” Dr Brown said.

Using the coroners’ rolls, which contain the names, events, locations and even the value of murder weapons, researchers constructed a street atlas of 354 homicides across all three cities.

Researchers said a mix of young male students and booze may have often been a “powder keg” for violence.

Victims or witnesses of the time had a “legal responsibility” to alert the community and “it was mostly women who raised hue and cry, usually reporting conflicts between men to keep the peace,” Dr Brown said.

Scientists suspect the medieval sense of street justice and the ubiquity of weaponry in everyday life at the time may have caused even minor infractions to lead to murder.

For instance, the map reports cases of altercations following “careless urination” and “littering” that ended in homicide.

“Circumstances that frequently led to violence will be familiar to us today, such as young men with group affiliations pursuing sex and alcohol during periods of leisure on the weekends. Weapons were never far away, and male honour had to be protected,” Dr Eisner said.