The great hall is one of the most enduring images from the middle ages – and with good reason. Surviving written sources as well as archaeological and architectural analysis all attest to the importance of the hall within manor houses, castles and palaces during festive periods.

Taking mostly English examples, it’s clear that the social dynamics of a great hall were all-important to its role. But the warmth of the hall is also mentioned frequently.

A story from Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, completed in 731, contrasts the cold outdoors with the pleasure of the fireside. Edwin of Northumbria and his advisors were discussing the merit of conversion to Christianity. As the conversation moved, one among them compared human life with the flight of a sparrow through the hall where the king might sit with his men in winter: “In the midst there is a comforting fire to warm the hall; outside the storms of winter rain or snow are raging.”

Another famous hall of Old English literature, Heorot from the epic poem Beowulf, was built for King Hrothgar of the Danes. The noblest of all halls, it was the stage for welcome, entertainment, displays of lordship – ring-giving – feasting, flirting and sleep. And the scene of the nocturnal devastation wreaked by the monster Grendel and his mother, both of whom were dispatched by Beowulf.

Up to the 13th century, the great hall remained the focal point of the household, and the primary location for heat. The hearths of the 12th-century hall can be seen in the foreground (on the ground) of this photograph of Warkworth Castle, also in Northumberland. The main source of heat would have been an open fire or a charcoal-burning brazier.

The Norman hall at Warkworth would have been about 17 metres by 12 metres, so not vast, but built of stone and therefore a place that would retain heat. Since it was warm, the hall would have been at a premium as a place for servants to sleep, especially in colder months. While the lord slept in his chambers, the servants took pot luck around the complex.

The great hall was the place for food, prepared and consumed for the most part during the day, prandium, but also into the evening, cena and by candlelight, making it one of the best-lit places in the complex of buildings that made up a lordly dwelling. Lighting would have been by tallow candles, also known as Paris candles, which feature regularly in medieval accounting rolls.

The hall was a place to display tapestries (especially from the 14th century) and wall paintings, and for dancing, music and poetry, from the troubadours of southern France to the Minnesänger (singers of love songs) of Germany.

Christmas entertainment in the hall, over the 12 days of the season, would involve the whole household and guests. They would be party to the procession of the boar’s head, games of social inversion such as the Bean King (whoever found a pre-dropped bean in their food became king for the day), and further gift-giving, singing, and in the case of Henry II’s court, a jump, a whistle, and a fart from Roland the Farter.

Changing spaces

Changes in the function, design and place of the great hall from the 13th to the early 16th century are covered in wonderful detail by Chris Woolgar in The Great Household in Late Medieval England. Among the many changes was a move to consolidate what had been separate buildings.

The hall was now part of a complex of rooms that also included the kitchen, buttery and pantry – separated from the dining space by a screen, and on the other side by the “solar”, the private quarters for the lord (so named for its position to catch the sun for warmth and light).

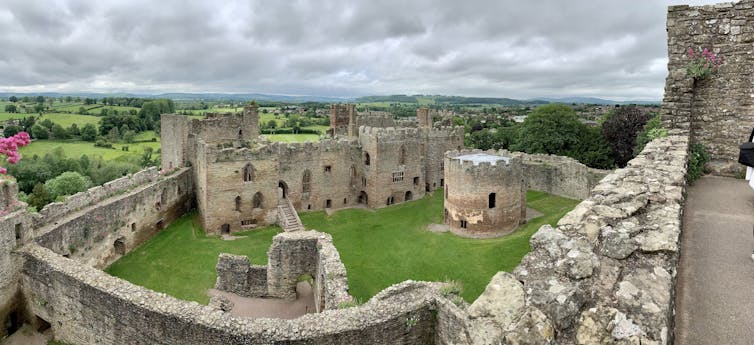

Re-building for domestic purposes can be seen at Ludlow Castle in the 1280s, with the insertion of these new elements. It can also be observed at almost exactly the same time a little further south at Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire, where William de Valence made a series of alterations.

By the 15th century, the great hall was just one of a number of different spaces for entertaining. Nevertheless, it continued to hold an important place for the household including over the Christmas period. The hall provided the arena for dramatic episodes in medieval storytelling: the early 14th-century alliterative poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight uses a feast at new year, in the depth of winter, as the setting for its playful tale of gamesmanship, honour and chivalry amid the warmth and comfort of the hall.

Medieval society was used to hardship, being always only two bad harvests from mass starvation. The great hall itself was also a reminder of the social hierarchies of lordship. Not everyone was invited in – only servants, guests and family.

Nevertheless, its role as a warm place and social hub is worth some thought. There are, perhaps, areas of resonance with our current situation: a cold winter, difficulties heating rooms, and the importance of a shared warm space.

Giles Gasper receives funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, The Leverhulme Trust, and Research England.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.