Archaeologists in Sweden have discovered the medieval burial of an extremely tall man who was buried with a long sword — one that was nearly two-thirds of his height — and may have been a nobleman who supported the region's ill-fated union with Denmark and Norway.

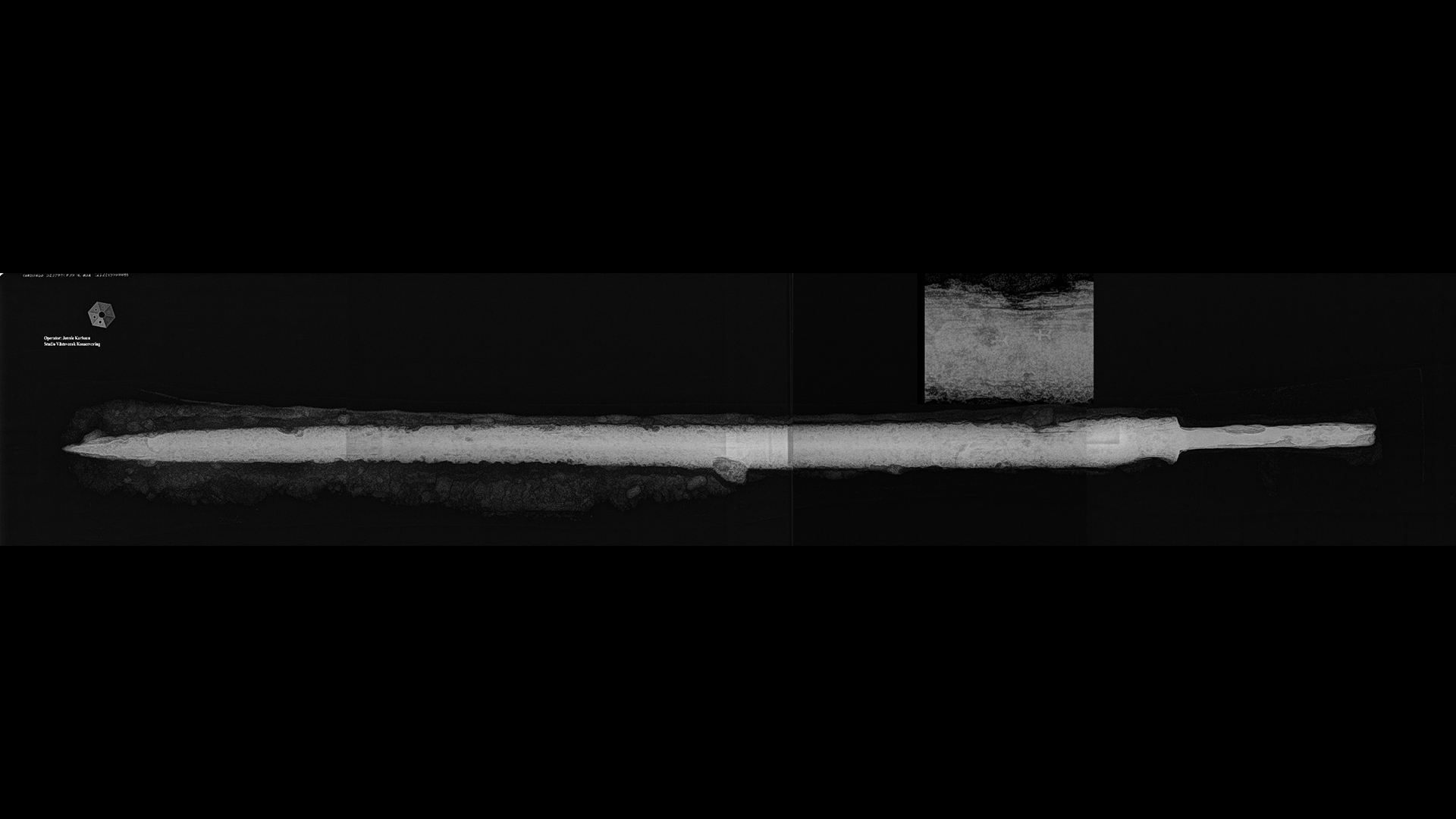

The sword, which is over 4 feet (1.3 meters) long, seems to have been inlaid with a different metal to form small Christian crosses, excavation leader Johan Klange, an archaeologist with the Halland Cultural Environment, an agency of the local government, told Live Science.

Even taller than the sword was the man in the grave. Klange said he stood about 6 feet, 3 inches (1.9 meters) tall — an impressive height for the turn of the 16th century, when the average male height in Sweden was about 5 feet, 5 inches (1.65 m), according to experts.

Archaeologists found the burial during excavations of the "Little Square" — "Lilla Torg" in Swedish — at the center of the city of Halmstad, on the west coast of Sweden near Denmark. The grave of the tall man was the most prominent found in excavations of the Franciscan friary at the site, which was active from 1494 until it was destroyed in 1531 during the Protestant Reformation, Klange said.

The sword buried alongside the man was the only grave good found among 49 graves at the site and may have signified that the man was a member of the high nobility. The archeologists think the man may have been a wealthy supporter of the Kalmar Union, in which a single king ruled Sweden, Denmark and Norway between roughly 1397 and 1523.

Related: Medieval fighter may have died with an ax 'stuck in his face,' reconstruction shows

"We hypothesize that he was part of the high nobility of the Kalmar Union, and may have owned property in both Sweden and Denmark," Klange said. "These people became very, very powerful."

Catholic burial

The grave was found in mid-December during excavations at the site, which was discovered during roadworks in the 1930s, Klange said.

The friary represented the Roman Catholic Church and had been destroyed during Sweden's Reformation, which lasted from about 1527 until 1593.

The grave was found within the boundaries of the friary church, so it is likely that the man and two other people buried nearby — a man and a woman — were members of a noble family who lived in the region, Klange said.

Examination, including DNA analysis, of the bones in the graves will now investigate whether the three people were related, he said.

The sword, too, will be analyzed, Klange said; it seems to be in the late medieval European style known as a "longsword" or "hand-and-a-half sword," which could be used with either one or two hands.

Although the sword was made of iron, which is susceptible to rust, it is well preserved. However, the blade snapped near the hilt, likely from the roadworks in the 1930s, he added.

Kalmar Union

Klange said more research will investigate whether the man was a noble under the Kalmar Union, which was partly an effort to counter the influence of the Hanseatic League of northern German towns and merchants, which at that time dominated trade in the Baltic and North seas.

Harald Gustafsson, a historian at Lund University in Sweden who wasn't involved in the excavations, explained that the Kalmar Union was a "personal union" under the same monarch, in which all three kingdoms retained their own laws and institutions.

But the Kalmar Union was riven by factional fighting, and the discord culminated in 1520 with the "Stockholm Bloodbath," in which King Christian II executed almost 100 of his enemies.

"After that there was very little sympathy in Sweden for the union," Gustafsson said.