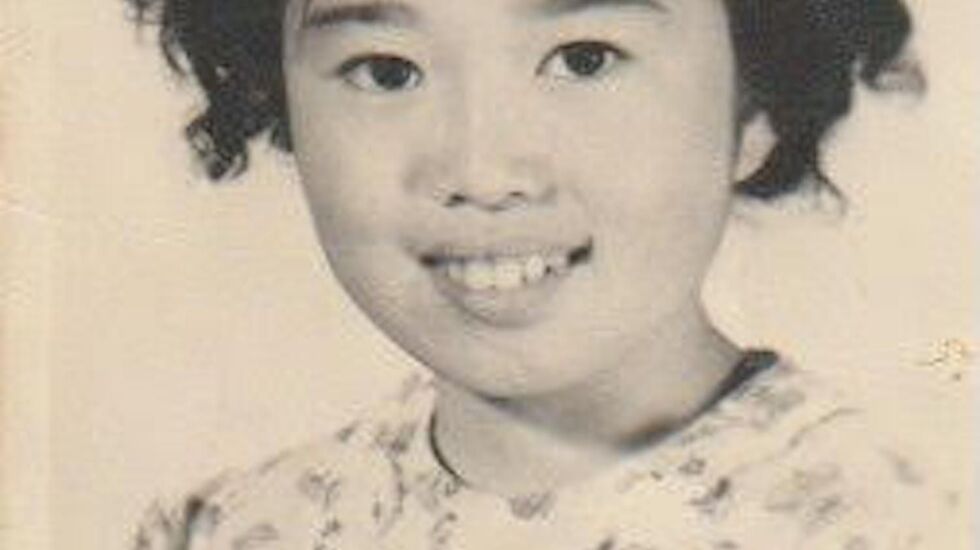

As a baby, May Nakano lived in a 448-square-foot wooden shack in Canada where ice formed inside during the winter.

After Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor, Canadian authorities, like the U.S. government, forced tens of thousands of people from their homes and into internment camps because they were of Japanese heritage.

Little May’s parents Masao and Hisako Kawamoto had to move from their strawberry farm close to the West Coast to a remote camp near Lillouet, British Columbia, where the baby girl spent her first winter.

Later, at school, her teacher couldn’t pronounce her birth name of Satsuki, so she was called Sally.

But she’d been taught to stand whenever she heard her name, so the little girl jumped up every time she heard Dick-and-Jane reading lessons with lines like: “See Sally play.”

So she was renamed again, this time as May for the month in which she was born.

In the years after the war, her family tried to start a new farm in Langley, British Columbia. Her father cleared land by hand and blasted it with dynamite, a material Japanese Canadians had been barred from possessing during internment.

Young May loathed back-breaking farm chores, according to her cousin Linda Kawamoto Reid, and would yell, “I hate these plants!”

“Her father would chase her around the farm to discipline her,” Reid said.

“She wanted to be a vet, but her parents said the only profession suitable for a woman was nurse or teacher,” according to her daughter Megan Nakano.

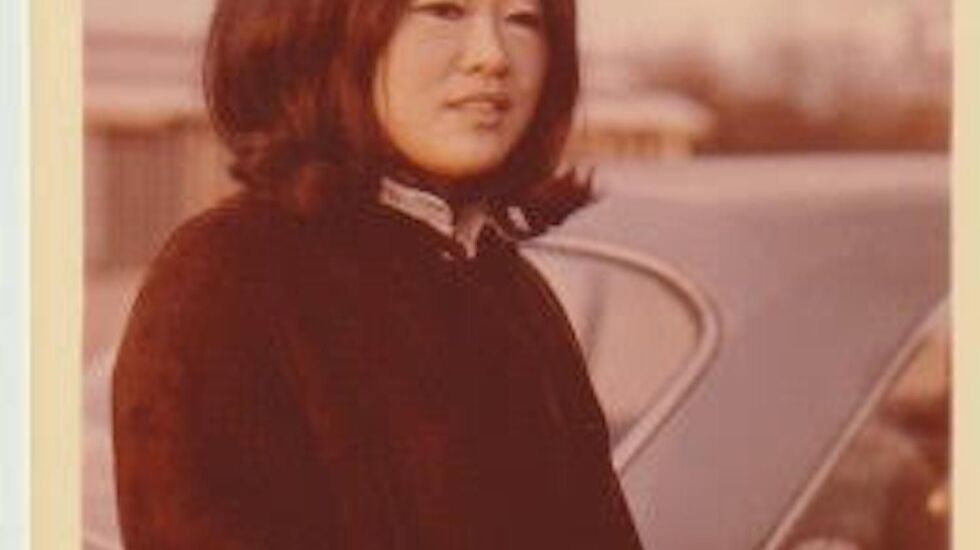

She decided to immigrate in 1967 to Chicago, where she had a job lined up with Merrill Lynch. She moved into a YMCA downtown.

Ms. Nakano developed a reputation for being confident, witty and blunt.

“She was one of those figures who stood out in the Japanese community,” said Koren Vanzo, who is half Japanese. “She was very vivacious. You always got a direct answer from that woman.”

“She was direct, opinionated, profane, funny, well-informed and very kind,” said Karen Kanemato of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society.

She was a role model to younger relatives, who saw her as stylish and unafraid to stand up for herself, according to Reid.

Ms. Nakano worked as a broker’s assistant and legal secretary before becoming an assistant manager for 15 years at Heiwa Terrace in Uptown, a 200-unit Department of Housing and Urban Development senior building started by the city’s Japanese American community.

She also worked as a secretary at the Midwest Buddhist Temple.

Ms. Nakano, 78, who had heart trouble, died July 4 at Wesley Place nursing facility on Foster Avenue, her daughter said.

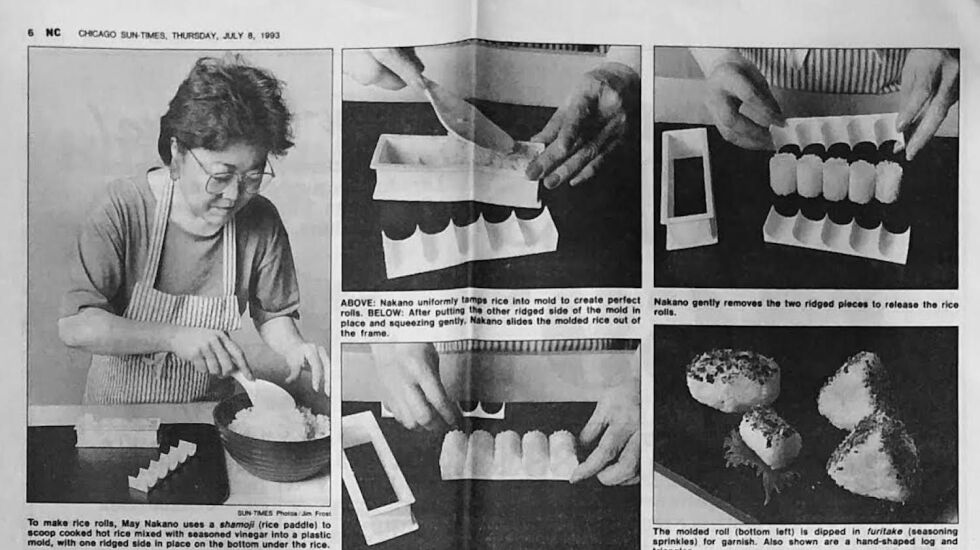

A gifted home cook, she did demonstrations on making artful boxed lunches, sushi, gyoza and somen noodle salads at Marshall Field’s and for the Japanese American Service Committee. Her son Matt said her cooking lessons were much sought-after and that she auctioned them off to benefit the Francis W. Parker School, which her children attended.

In a 1993 interview on her culinary skills, she told the Chicago Sun-Times: “With Japanese lunch, the visual is everything.”

At Heiwa Terrace, Ms. Nakano did a little of everything.

“I’m still using a record-tracking system that she had,” said Vanzo, an assistant manager there.

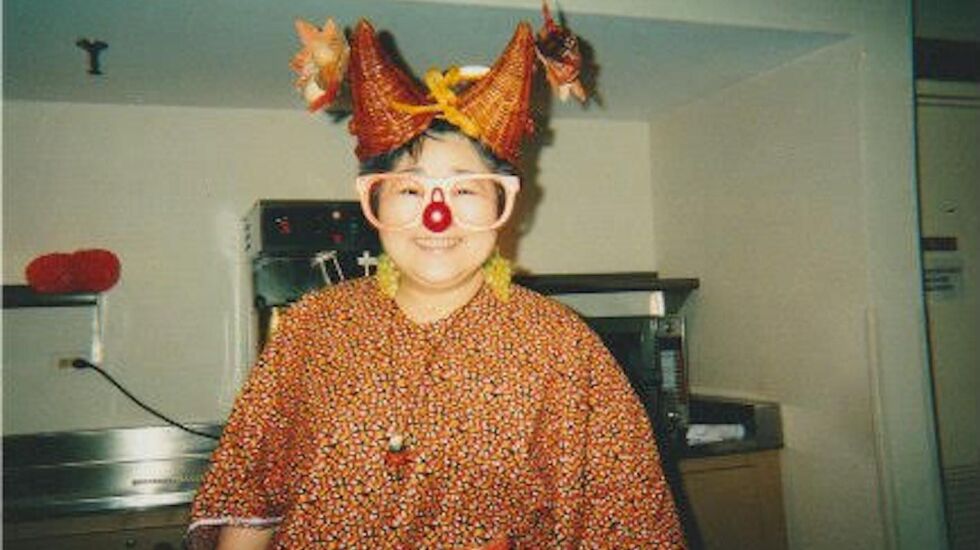

She monitored the health of residents and kept in contact with their families, dealt with fire alarms from cooking mishaps, decorated for the holidays and dressed up as an Easter bunny or a Christmas elf.

“She loved the residents,” her daughter said.

At Halloween, she’d wear homemade costumes that transformed her into a piece of sushi, a pirate or Queen Elizabeth, complete with a stuffed corgi.

“I have been here 36 years,” said Rachel Tucker, a security supervisor at Heiwa Terrace. “When I first came, I was the only African American. May, from Day One, she opened her arms to me. She knew my mom and dad, saw my kids grow up. My mom was blind and in a wheelchair, and she would come over and sit with her, talk to her, give her massages.”

Ms. Nakano enjoyed TV shows about veterinarians and English royals. Her love of the monarchy was instilled from growing up in the British Commonwealth.

Before she was born, her father bought a $180 General Electric radio — a pricey purchase in those days. The family used it to keep informed of news and rising anti-Japanese sentiment.

Though Japanese Canadians weren’t surrounded by the barbed wire and armed guards of U.S. camps, “It was worse here than the States,” said Reid, a research archivist with the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre in Burnaby, B.C.

Because Canada’s restrictions weren’t lifted until 1949, the exile of Japanese Canadians from their West Coast lasted till about four years after World War II ended.

In Canada, many men of Japanese heritage initially were separated from their families and sent to camps to do roadwork. The government paid for their internment by auctioning their possessions for “a pittance,” Reid said. They lost their farms, vehicles and 1,200 fishing boats.

Ms. Nakano’s father’s pride, his GE radio, was sold at auction for $51, Reid said, and his 10-acre farm went for half its value.

After the war, a second uprooting happened, Reid said. Japanese Canadians were pressured to move east of the Rockies or relocate to Japan. Until 1949, they could not return to the West Coast, where racism and espionage fears had helped fuel the policies forcing their dispersal across Canada and to Japan.

Later in life, Ms. Nakano herself became a resident of Heiwa Terrace, where she’d take the canned food donated to the facility and use her tiny kitchenette to transform it into delicious meals for the staff, Vanzo said, dropping it off with a breezy, “Here’s your lunch today.”

Tucker ignored her aversion to avocados when Ms. Nakano made her signature salad: “Forget about the avocados giving me a stomach ache. I had to have it.”

At Heiwa Terrace, her son said, Ms. Nakano “was always the one making people laugh.”

Kanemoto said she took care of elderly neighbors who were ailing and served on the boards of the Japanese American Citizens League and the Japanese American Service Committee.

Ms. Nakano is also survived by her brother Ted. A memorial — which will be livestreamed at bit.ly/MayNakano — is scheduled for 11 a.m. Sept. 24 at the Midwest Buddhist Temple, 435 W. Menomonee St.