The long-awaited Adult Swim adaptation of Uzumaki, the horror manga by Junji Ito, has fans twisting themselves into knots in anticipation. While Ito’s most iconic work has been adapted before, the prospect of an achingly detailed recreation of his immersive drawings via the medium of animation just hits differently.

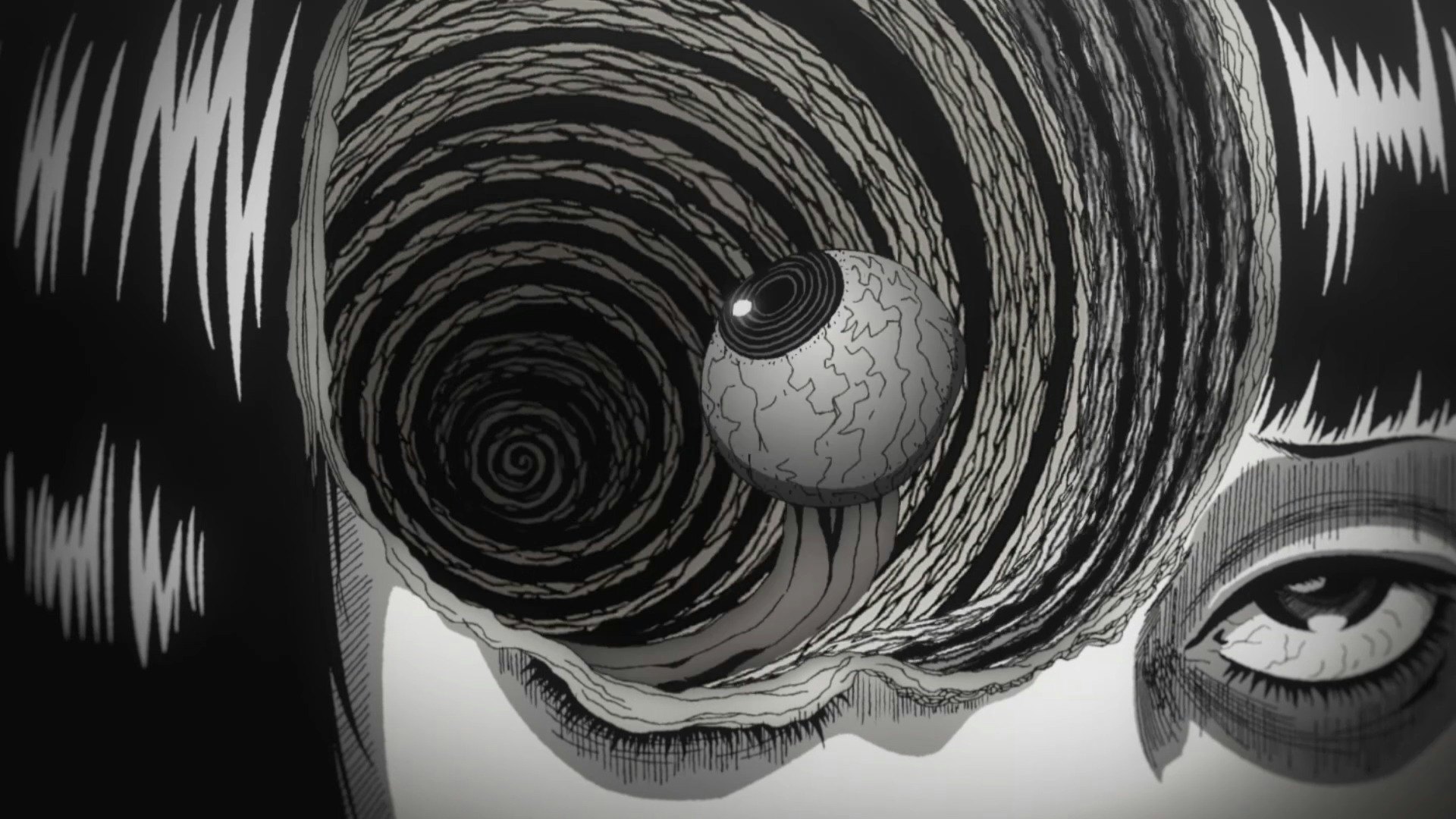

Uzumaki imagines a seemingly normal Japanese town that becomes engulfed in spirals. These simple shapes turn sinister, whether it’s a teenage girl’s out-of-control curly hair, boys turning into slimy snails, or whirlpools that consume all who fall into them. One of the most mundane parts of life, a naturally occurring shape you can find practically everywhere, becomes a hellish curse that engulfs all who fall into its spin. The four-part series (critics received only the first part before the premiere) is an achingly faithful recreation of the manga, panel-for-panel in most scenes, with Ito’s hyper-detailed art style given a kind of uncanny fluidity through movement. The combination of hand-drawn animation, CGI, and motion capture gives Uzumaki a decidedly unreal sensation, as though everyone moves just a little too smoothly to be truly human.

For many manga lovers, Junji Ito was their first introduction to horror in the medium, and he certainly made an impact. It’s now a challenge of sorts to dive head-first and spoiler-free into his books, which offer plentiful examples of the manga version of a jump-scare: dare you turn the page and see what comes next? Even non-horror fans recognize his style: intricate, outlandish yet upsetting, offering ideas so unexpected that you had no idea they’d haunt your nightmares until he introduced them to you.

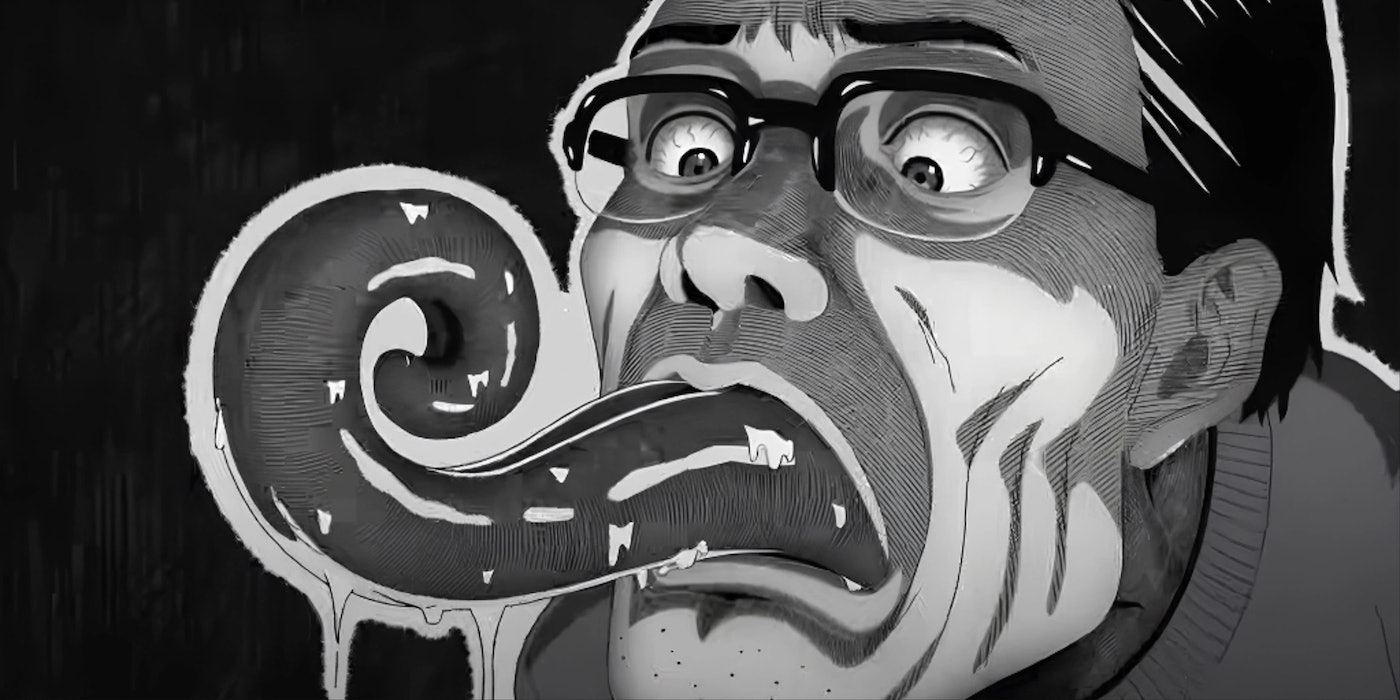

Part of Ito’s appeal is that his plots are, well, kind of ridiculous. If you were to describe to someone what happens in, say, “The Enigma at Amigara Fault” or Gyo, they’d probably laugh. Giant sentient balloons of people’s faces track down their human doubles to murder them; holes shaped like naked bodies are discovered on the side of a mountain; a horde of undead fish with metal legs powered by a nasty stench take over dry land; a woman’s face is peeled away to reveal layers like an onion. Sounds like a bad trip, right? Therein lies Ito’s genius. What should seem silly or camp becomes disgusting and truly upsetting.

Ito taps into a near-primal fear through this outlandishness. In Uzumaki, things you’d never consider become phobias once you realize how inescapable their horrors are. Spirals are everywhere, including on and inside our bodies. What happens when something you literally cannot escape from turns against you? Losing control is a universal panic. Ito just taps into that unease through unique methods. Maybe you won’t twist into a knot with their loved one, but you’d definitely feared losing control of your limbs or being separated from your partner. In the anime adaptation, everyone reacts in abject terror, their faces twisted like rubber, and it’s hard not to be affected by their fears.

Ito’s influences are plentiful, largely from the manga world but also from artists like Dali and Giger. In many ways, he is the 21st-century heir to Lovecraft, a man obsessed with the infinitesimal nature of humanity in the context of our ever-expanding and fathomless universe. What is more terrifying than realizing you’re but a meaningless speck in the face of a doom that devours all without emotion? This is most evident in one of Ito’s cosmic horrors, Hellstar Remina, about an alien planet on-course to destroy Earth and the violent hysteria this future inspires in humanity. Hopelessness is its own special hell.

But you can’t talk about Ito without mentioning the artwork. It makes the unreal into something you’ll never forget. Faces are detailed but uncanny, with agape mouths just a little too wide and brows sopped in sweat. Emotions are big but grounded. Not everything is graphically bloody but his body horror rivals that of David Cronenberg in its malleability of the body. Limbs become elastic. Skin stretches indefinitely. In anime form, the addition of movement makes real what the reader was forced to imagine, and it’s a tough watch. If horror icons like Cronenberg and Clive Barker want you to revel in the physical transformation, Ito allows no such catharsis. In Uzumaki, when various characters twist and mutate into spirals, the reader is denied a release from their pain.

The anime adaptation is ruthlessly faithful to its source material, and it’s for the better. If the formula ain’t broke, then don’t fix it. It’s a technologically sophisticated yet no-frills take on something that has endured for decades. Even those highly familiar with the manga will be unable to suppress their shudders at what Uzumaki reveals. For new audiences, prepare to never be able to look at your own fingertips the same way again.