To help combat the effects of global warming, scientists are toying with an innovative idea to shield our planet from the sun with a spaceborne "umbrella" of sorts.

"In Hawaii, many use an umbrella to block the sunlight as they walk about during the day," István Szapudi, an astronomer at the University of Hawaii Institute of Astronomy, said in a statement. "I was thinking, could we do the same for Earth and thereby mitigate the impending catastrophe of climate change?"

The reason carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases contribute to global warming is that they trap sunlight around our planet that should be released back into space, ultimately leading to rising temperatures. But it's the sun, and not greenhouse gases, that creates the heat to begin with. That opens up the idea of building Earth a shade.

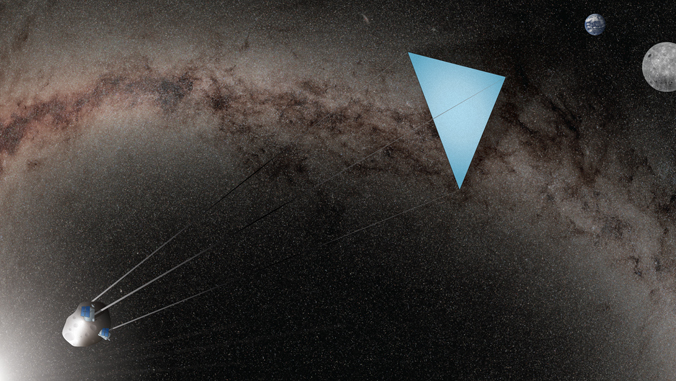

So, Szapudi drew up an "umbrella" of his own. It would rest at the L1 Lagrange point between the sun and Earth, hypothetically joining sun- or solar-wind-observing probes such as the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) and Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) that dwell there today. In theory, a large-enough solar shield could effectively block around 1.7 percent of solar radiation at L1, enough to prevent a catastrophic rise in Earth's temperatures.

Related: NASA searches for climate solutions as global temperatures reach record highs

However, any sort of solar shade is bound to face a stark engineering challenge: At L1, they'd be subject to both the sun's and Earth’s gravities while experiencing a constant torrent of solar radiation. A viable shade would thus need to be massive — weighing millions of tons — and made of a material sturdy enough to stay in place and stay intact. Simply, we don’t have a practical way of launching that much stuff into orbit.

But to get around that issue, Szapudi proposed, much of the material itself can come from space — from a captured asteroid or even lunar dust. That matter could theoretically serve as a counterweight, tethered to a much smaller shield weighing only around 35,000 tons. Right now, even such a smaller shield would be far too heavy for a rocket to lift, but with advances in materials, Szapudi’s study suggests we could manage the feat in several decades.

Szapudi's apparatus falls under the, well, umbrella of solar geoengineering: the controversial idea of alleviating global warming by physically reducing the amount of sunlight that reaches Earth's surface. Other solar geoengineering ideas include pumping aerosols into the atmosphere and editing clouds to reflect more sunlight away into space.

The study was published on July 31 in the journal Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences.