‘Masquerade, Make-Up & Ensor’, a new exhibition at MoMu in Antwerp, examines the correlation between James Ensor and contemporary creative figures. A founding member of the avant-garde group Les XX, Ensor is championed as one of Belgium’s great proto-modernist artists.

Throughout his practice, ‘the mask’ was a recurring motif, often referencing the make-up trends of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. As art historian Susan M Canning observes of the painter and printmaker’s work, ‘masking, make-up and arrangements of masks […] promote the disruptive and transgressive subterfuge of artifice’.

Inside ‘Masquerade, Make-Up & Ensor’ at MoMu – Fashion Museum Antwerp

‘Ensor was a perfect way to feature make-up and hairstylists in MoMu for the first time,’ says Elisa De Wyngaert, who co-curated the show with Kaat Debo and Romy Cockx. ‘But also a way to discuss beauty ideals and everything surrounding the fashion industry.’

Also central to the exhibition’s genesis were three points of exploration that De Wyngaert, Debo and Cockx wanted to highlight: Why do we wear masks? Why are people so afraid of visible ageing? How do we deal with ideals of beauty that are always changing and are impossible to achieve?

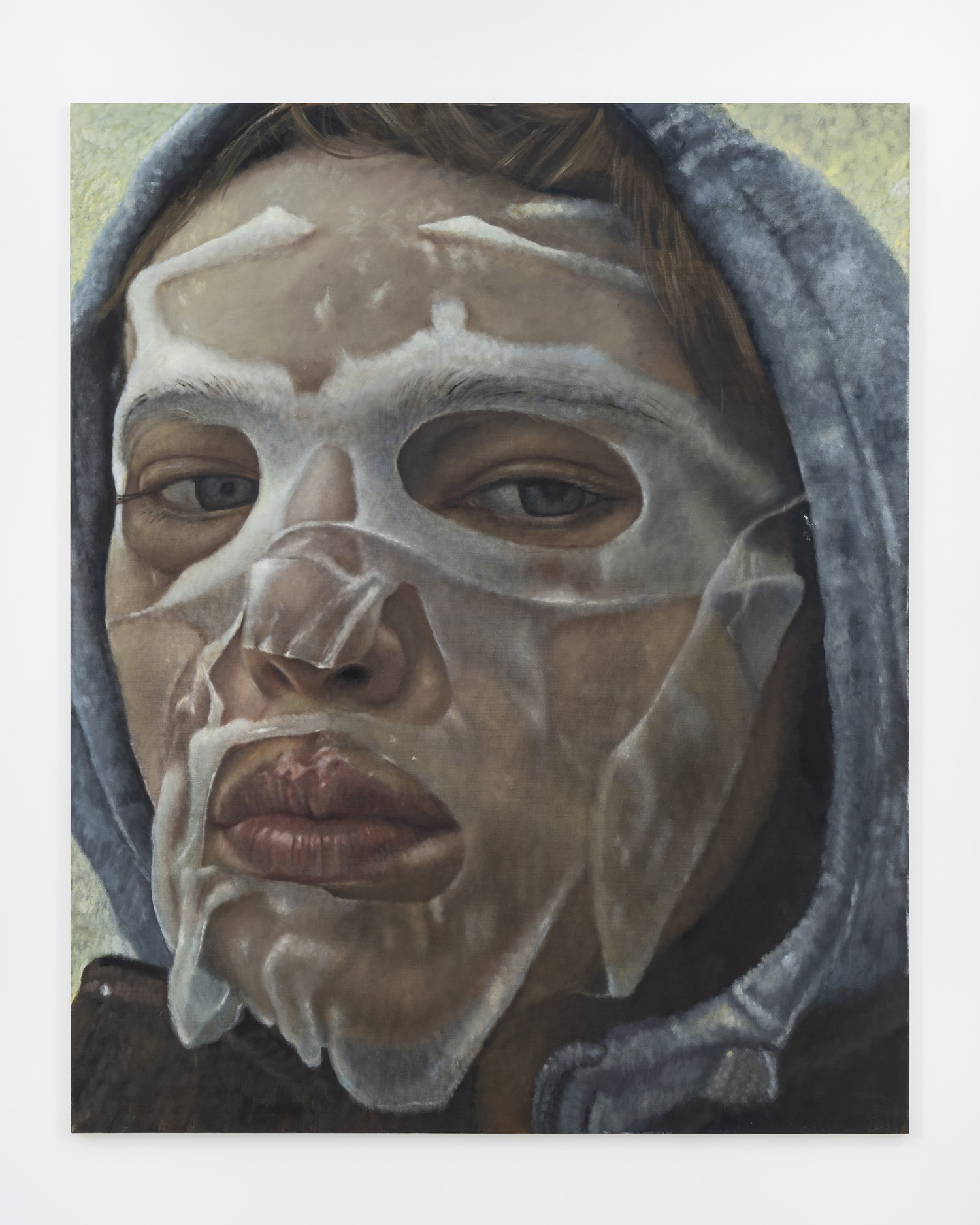

The multimedia works on display span paintings, photographs, scrapbooks, mannequins, videos and more. A small series of paintings by Ensor marks the start of the exhibition, followed by self-portraits of mammoth proportions by Issy Wood, highlighting the painter’s discomfort with being photographed. Elsewhere, Genieve Figgis’ ‘grotesque and beautiful’ characters hang on canvases against the backdrop of lilac curtains decorated with huge bows (a highlight of Janina Pedan’s exhibition design).

American photographer Bruce Gilden’s disarming close-ups of his subjects are mirrored in a selection of Cindy Sherman’s Head Shots series, while artist Tschabalala Self explores the idea of persona and politics. ‘A lot of the time beauty ideals reflect the politics you want to align yourself with,’ she considers on a nearby wall panel. ‘People often underestimate the political aspect of beauty.’

From the worlds of fashion and pop culture, Pat McGrath’s viral ‘porcelain doll’ make-up, conceived for John Galliano’s Maison Margiela 2024 Spring Summer Artisanal collection is presented with Another Galliano fixture, the ‘Rosalie’ doll. The latter can be found in a space dedicated to the master of hair Julien d’Ys, as well as a cloud-like sculpture he created for Wallpaper* in 2022. Items from Rihanna’s Fenty line and Martin Parr’s 2019 beauty campaign for Gucci both make cameos.

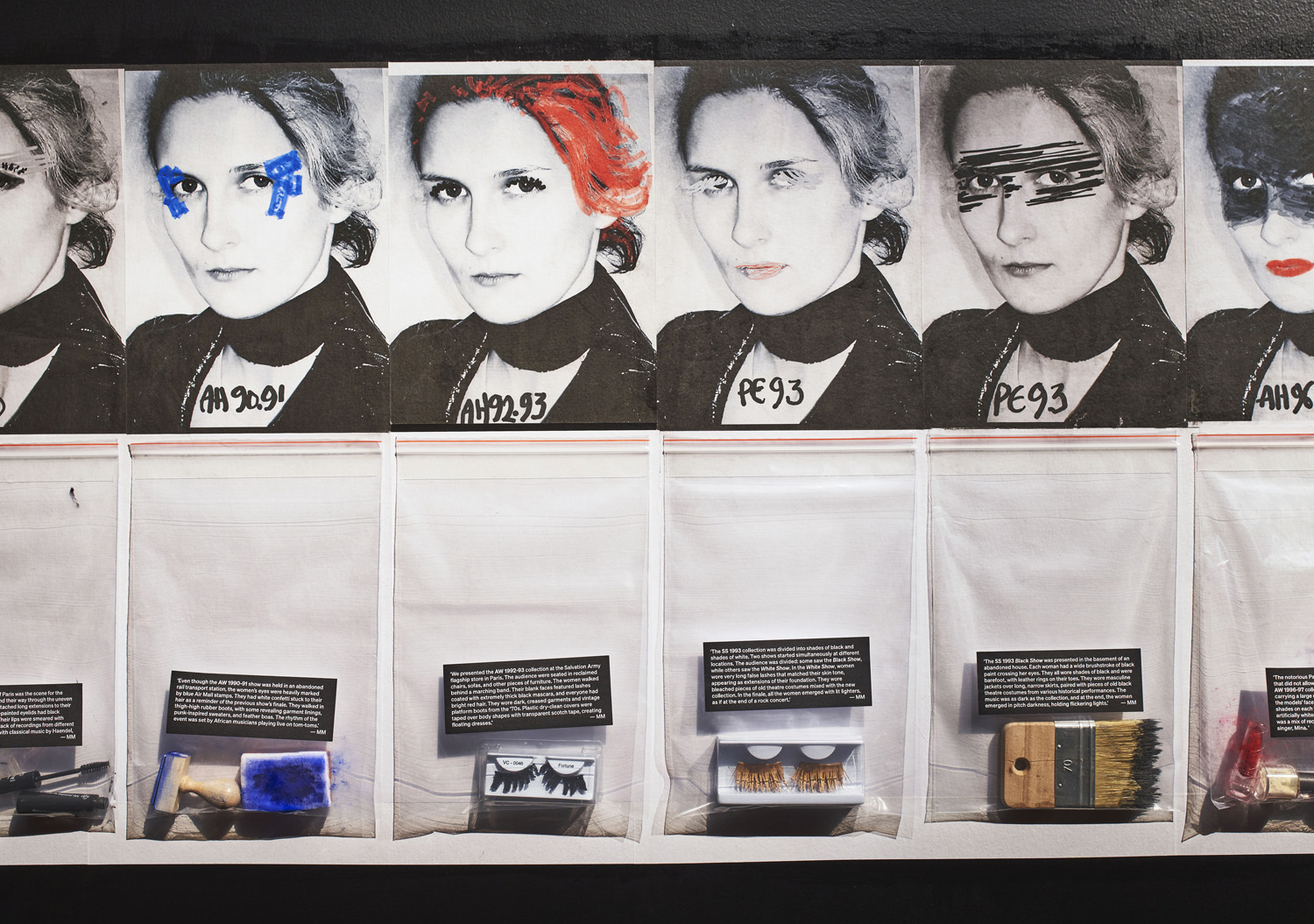

Perhaps the most significant, however, is the contribution of make-up artist Inge Grognard. Here, the looks she created for Maison Martin Margiela between 1988 and 2008 are shown almost like posters, the respective products used to create them hanging in sandwich bags below, while a video of Grognard today concludes the exhibition. ‘The film is very special; you don’t often hear the voice of make-up artists,’ notes De Wyngaert.

‘I am still flabbergasted by the amount of research [hair and make-up artists do]; they are true painters of fashion, the way they draw, the preparations,’ she continues. ‘True artists just working in a different medium. I didn’t think make-up was superficial [before], but the quality of the work, the reflection and depth, is something I’m just stunned by.’

For Cockx, whose focus was specific to the work and social landscape of Ensor, surprise was reserved for the language – and attitudes – surrounding make-up application. ‘What really struck me was, when looking at the fashion magazines from the 19th century, they literally compare make-up to applying paint [on a canvas],’ she adds.

Though not explicitly gendered, ‘Masquerade, Make-Up & Ensor’ strongly focuses on women, with whom the eccentric and opinionated Ensor had a complicated relationship. His 1925 poem, On Women, for example, is a deeply misogynistic text. Yet he also lived with – and frequently painted – his mother, aunt and sister.

‘Women wearing too much make-up is still perceived as, “what is she hiding?” not “oh, she wants to express herself”,’ suggests De Wyngaert. ‘There’s so much judgment; both in Ensor’s time and still today. It’s this kind of impossibility – how do you ever win? That is something we wanted to leave space for. Women constantly feel they are not in charge of their own bodies – we wanted to explore where these fears or anxieties come from.’

In a later scene, fears of ageing are projected onto a would-be bride. Surrounded by a sheer curtain, she stands before a three-piece mirror, the extravagance of a Christian Lacroix gown mirrored in her hair, which is piled high in an exaggerated style that riffs on the beehive.

‘That was the most experimental installation, with Cyndia Harvey,’ shares De Wyngaert, alluding to the revered British hairstylist. ‘It was an idea from a previous interview with Lacroix for “Echo: Wrapped in Memory”. He told me about this obsession with Miss Havisham and that planted the seed. I hope it gives some strength, acknowledgement and empowerment to ageing women, or ageing people for that matter,’ she concludes.

‘Masquerade, Make-up & Ensor’ is on display at MoMu - Fashion Museum Antwerp until 2 February 2025