In 1946, Los Angeles Examiner sportswriter Vincent X. Flaherty was interviewing “Ice Capades” star Donna Atwood, who was so famous that Disney based Thumper’s “Bambi” ice-skating sequence on her.

In his column, Flaherty wrote that he was tossing questions Atwood’s way without much thought — most of them about fan mail from lotharios.

Then, “Ice Capades” publicist Maryfrances Ackerman stepped in, suggesting he ask “something sensible.”

“What’s the matter, Flaherty, are you off your trolley?” she asked. “Why don’t you write about Donna’s miraculous rise to the top?... When she was 15, she won the national junior figure-skating championship. ... She still spends much of her time with the servicemen in the military hospitals.

“You’re a sportswriter, aren’t you?” she asked the chastened writer.

Four years later, the publicist married Bill Veeck, of whom she would say, “Keeping up with that man is tougher than keeping track of a couple of hundred people on tour” with the “Ice Capades.”

Maryfrances Veeck was a resourceful, energetic partner as her husband became president and part-owner of the St. Louis Browns and the Chicago White Sox — twice. She did TV and radio shows with him in both cities, often doing research and booking their guests.

In his autobiography, “Veeck As in Wreck,” Veeck wrote about how she gracefully fielded questions about him selling his share of the Browns in the early 1950s, which resulted in their move to Baltimore and evolution into the Orioles.

“Whenever a cabdriver challenged her about moving the club,” he wrote, “the Veecks, she would point out, had no brewery or construction company going for them. ‘Bill has only one means of supporting our family,’ she would tell them. ‘The ball club. If you were in his position, what would you do?’ ”

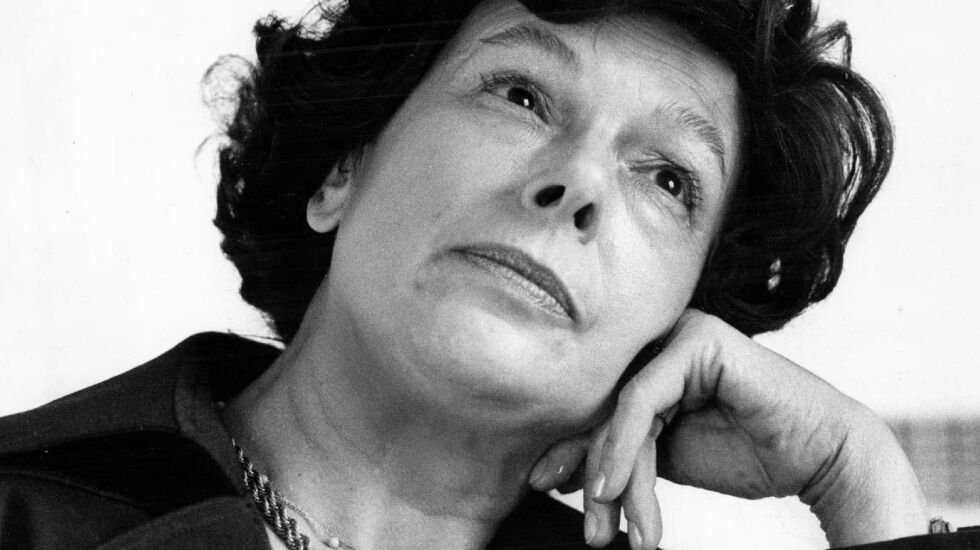

Mrs. Veeck, 102, died Sept. 10 at Montgomery Place retirement community in Hyde Park, according to her family.

“She was fierce and wonderful in all she did,” her son Greg Veeck said.

“Maryfrances Veeck was an active and very visible partner with Bill Veeck during their ownership tenures,” a written statement from the White Sox said. “She enjoyed amazing relationships across the baseball and entertainment industries, with the media and throughout Chicago society.”

She grew up in and around Pittsburgh, where her father Ray was an accountant and her mother Theresa Jane a nurse. Though often referred to as Mary Frances, she had no middle name, and her first name was correctly spelled Maryfrances, her son said.

She studied drama at what was then Carnegie Tech and got good reviews for acting in “Charley’s Aunt” and other shows at the Pittsburgh Playhouse. At one point, he said, she did a screen test with actor Fred MacMurray.

By her mid-20s, though, she was promoting the “Ice Capades.” Of the troupe’s late-1940s tour to London, “She said it was really depressing to see how bombed-out it was,’’ according to her daughter Lisa.

In 1949, she met Veeck, who wrote she was called “The World’s Most Beautiful Press Agent.” He’d already been president and co-owner of the minor league Milwaukee Brewers and Cleveland’s pennant-winning American League team. They were married the following year.

Future Baseball Hall of Famer Veeck dreamed up stunts to promote his teams, like sending 3-foot-7-inch Eddie Gaedel in to pinch hit and draw a walk for the St. Louis Browns and staging a Comiskey Park invasion by “Martians” to “capture” Sox stars Nellie Fox and Luis Aparicio.

He’s also credited with the exploding scoreboard at Sox park. “He got that from a pinball machine,” Mrs. Veeck once told the Chicago Sun-Times.

She contributed a few stunts of her own. She composed a letter the Browns mailed to parents of newborn boys, congratulating them on the birth of a potential rookie — and inviting them to a game. And she helped design the White Sox shorts uniforms the team briefly wore in 1976, according to Lisa Veeck.

Mrs. Veeck arranged multiple moves and households as her husband also tried his hand at ranching, public relations and investing and operating Suffolk Downs racetrack in East Boston. She did interviews with reporters while wrangling six kids and an iguana, an armadillo, guinea pigs, snakes, fish and Yertle the turtle. At one point, the Veecks had 21 canines.

The family settled in Chicago when Veeck headed the White Sox. But after a cancer scare following the team’s 1959 American League pennant, they moved to a rambling house on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Mrs. Veeck didn’t drive, so she got a big bicycle to shop and attend Mass.

“She was known for riding her three-wheeled tricycle into town with her cape on,” Lisa Veeck said.

Like her husband, Mrs. Veeck was a strong proponent of civil rights. In Cleveland in 1947, he signed Larry Doby, the first Black player in the American League. The Veecks often welcomed civil rights leaders, including Dick Gregory and the Rev. Jesse Jackson, to their Maryland home, according to the book “Bill Veeck: Baseball’s Greatest Maverick.”

They settled in Hyde Park after returning to Chicago in 1975 for another stint with the Sox.

She tutored people in reading at St. Thomas the Apostle Catholic Church and raised money for the Catholic Theological Union, where a gallery is named for the Veecks. She read books for the blind. And, Lisa Veeck said, “She and dad marched against handguns.”

“Bill and I have a real love affair,” Mrs. Veeck told the Sun-Times in 1985.

Their home was filled with music and Broadway soundtracks like “The Music Man.” They’d dance around, he on the wooden leg he got after being wounded while serving in the Marine Corps in World War II.

Bill Veeck once said his wife’s specialty was “getting me out of trouble after I get myself into it.”

She helped him heal after the approximately 35 surgeries he endured on his leg.

He planted hundreds of daffodils in the shape of “MFV” outside her bedroom, according to their daughter Marya, who said, “They came up every year.”

Mrs. Veeck was known for her wisecracks, wry sense of humor and ability to get things done. Her son Michael said that after he and his father talked at length about a leak in an aquarium they owned, they woke up to Mrs. Veeck soundlessly alerting them that the problem was worse than they thought.

“At daybreak,” Michael Veeck said, “I remember mom showing up in fins and a mask and a snorkel.”

Mrs. Veeck was a chic dresser who often wore outfits accented with the color turquoise.

Her husband died in 1986, and her children Juliana and Christopher died before her. In addition to four children, Mrs. Veeck is survived by seven grandchildren and a great-grandchild.

A celebration of her life is planned at 11 a.m. Nov. 12 at St. Thomas the Apostle Catholic Church, 5472 S. Kimbark Ave., followed by a reception at the Catholic Theological Union, 5416 S. Cornell Ave.

Greg Veeck said that every day his mother would compliment the people around her — “I like your hair” or “That color suits you so well” or, in the case of waiters and others in customer service, “This place couldn’t run without you.”

“A thousand kindnesses,” he said.