By 1971, Bob Babbitt was one weary Funk Brother. Motown sessions were running at 7am, 11am and 3pm, while the production team of Holland-Dozier-Holland held 7pm, 11pm and 3am calls. Little did Babbitt know, however, that his finger fatigue would play a key role in one of the classic sub hooks of the ‘70s.

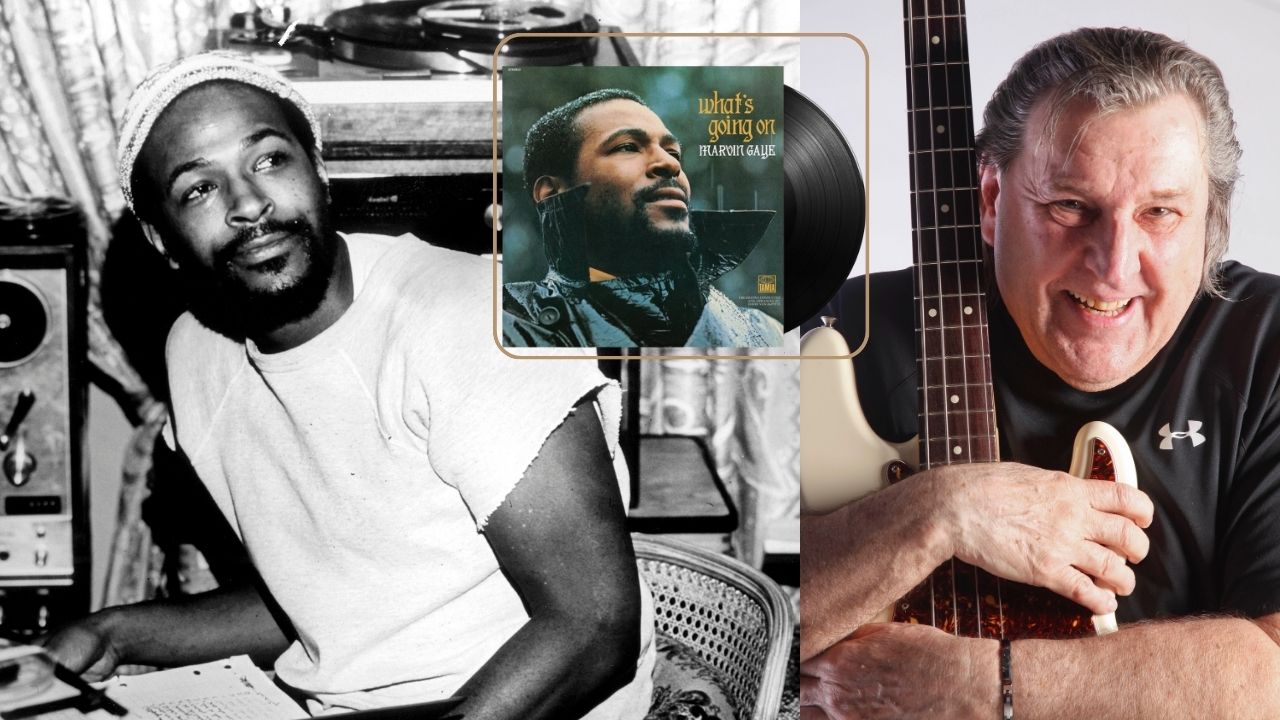

But first, the backstory: in January 1971, Marvin Gaye began recording his masterpiece, What's Going On. Politically charged and groundbreaking both musically and socially, the work has since been hailed as arguably the finest soul LP side ever made, and it's even been listed as one of the top five all-time albums in any genre.

The disc's nine songs were recorded in chronological order, with James Jamerson playing bass guitar on the first five cuts (including his legendary title track performance, purported to have been overdubbed while he was flat on his back on the studio floor). Sadly, Jamerson's demons had started to affect his consistency, so Babbitt was summoned for the final four tracks, including Mercy Mercy Me, (The Ecology), and Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler).

Inner City Blues, a brooding, bluesy meditation bemoaning the bleakness of inner-city living, was the album's final single, reaching number one on the R&B singles chart, and number nine on the pop chart. The backbone of the tune is a two bar call-and-response bass phrase that Babbitt more than made his own.

“When I got to the session, I saw that it was out of the ordinary,” he told BP back in February 2008. “Marvin was playing piano, and there were some outside musicians, like jazz drummer Chet Forrest, and Donny Hathaway's percussionist, Bobbye Hall. Over the next few days, as we ran down the music, you could sense Marvin was going someplace new: there were tempo changes, transitions, and exciting chord progressions unlike anything we had ever played. He was reaching and experimenting, but he knew what he wanted.”

On the ‘Inner City’ session in Hitsville Studio A, Gaye played piano without providing a scratch vocal. Babbitt sat on a stool in the curve of the Grand Piano, plucking his 1965 Fender P Bass, which had Labella medium flatwounds and a dampened household sponge placed under the strings by the bridge. He recorded direct only, with the sound coming out of the studio's big monitor speaker. Babbitt recalled the bass part being notated to some extent, with a few run-throughs occurring before the take, and no punches or fixes afterward.

“Hearing it again after all these years took me right back to the session, but my overall feeling is how fortunate I was to have played on an album that had such a huge impact on both musicians and society at large.”

As it turned out, the line he cut that day was only a portion of the final bass picture. Babbitt was called in to record a repeated one-bar phrase throughout all of the song's A sections. “The main part went pretty high up the fingerboard, and Marvin was used to hearing James Jamerson, who generally played on the lower part of the bass, rarely venturing above high C or D. I think he had me overdub the second part to fill out the bottom.”

Additionally, there were some sonic problems with the original bass track, leading Babbitt to be brought back to re-cut the original part, with an important twist. “It was late at night and I was really tired, so instead of reaching up for the high third on the G string, as I had on the original version, I slid up to it, and Marvin went, ‘Yeah!’ That led me to gliss into the note every time.”

The track begins with 12 bars of piano and percussion, with a bass pickup to the two bar sub-hook. Already comfortable with his gliss up to Gb, Babbitt embellishes with a quick slide up to Ab, a device he used tastefully throughout.

In the first verse, Babbit continues his sub-hook with some notable additions. First is his tendency to fill in the back half of the two-bar phrase. Second is his drop to low Gb instead of Eb, leading into beat three in bar 18.

“That's something that just happened: it’s a note in the chord and it worked nicely. The pickup fills, that occasional Gb, and the slides are my main contributions to the written two-bar bassline. And remember, I didn't have a scratch vocal going. If I did, I might not have filled as often.”

For the song's first B section, Babbitt was given the chord changes and the freedom to come up with his own part. “I recall wanting to play the section differently each time, to contrast the repetitive A section figure. For the first one, I stayed mainly on the root and varied the rhythms. This was something I was doing a lot at that point: you can hear the same approach on Mercy Mercy Me.”

For the second B section, Babbitt moves away from his root-only approach to play a melodic figure on the downbeat before returning to the third verse. “Really, most of those note choices came from my left-hand fingering of index and pinkie. As for the slides, as I said, I was tired, so I definitely fudged some throughout, which is where you’ll hear no sustain.” At the following bridge, Babbitt returns to his one-note-with-varied-rhythms concept, adding some cool octave drops in the last three measures.

As the final verse flows into the final bridge section, Babbitt returns to his melodic downbeat bridge figure, extending it dramatically to all four beats. Four bars of the main lick then give way to a modulation a whole-step down, keyed by a cool Babbitt pickup. “I knew the key change was coming, so you could look at it as me staying in Eb minor for the first two notes, while the last two are a chromatic lead in to the Db on the downbeat.”

Realising the track is ending, Babbitt gets loose in Db minor. After playing the first half of the two-bar phrase the same way he had been in Eb minor, he improvises in the second half. Remember that the one-bar overdubbed loop part is also present in the new key. This section transitions to a reprise of What's Going On, without bass, to close the album.

Babbit, who plucked the part using mostly his middle finger (supported by his index finger behind it), with the occasional index pluck, offered this advice: “Play it with a metronome slowly at first, to get the notes. Then gradually increase the tempo, even past the track pace; then return to the track tempo. You would think with the swing feel, the part sits behind, but it's pretty much square on the beat. Listen to the song to get the flow of the band, then dive in.”