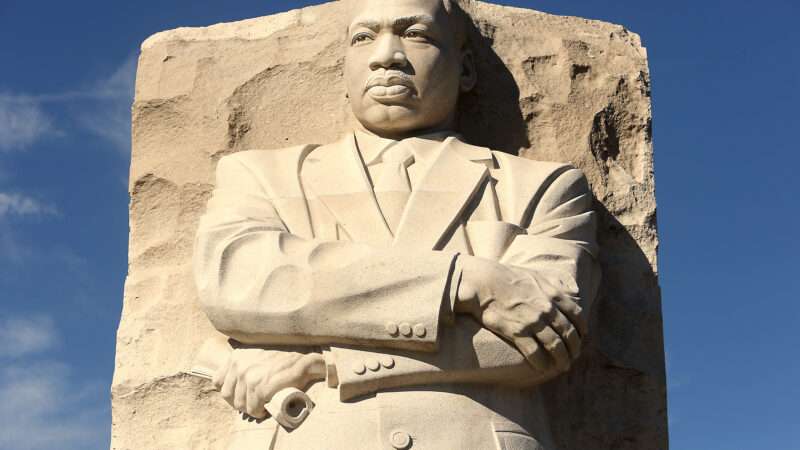

"I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,'" declared the civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., 60 years ago today.

In 1963, the United States was surely far from living out that creed. Addressing 250,000 people from the steps of a monument to the man who had issued the Emancipation Proclamation a century earlier, King pointed out that

the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land.

In 1963, I was a 9-year-old about enter my recently desegregated fourth grade in Washington County, Virginia. That was nine years after the Supreme Court's unanimous Brown v. Board of Education decision had ruled that America's public schools had to be racially integregated. Despite the ruling, Virginia's legislature adopted a program of "massive resistance" to racial desegregation, at one point closing down schools rather than admitting black students to the same classrooms as whites.

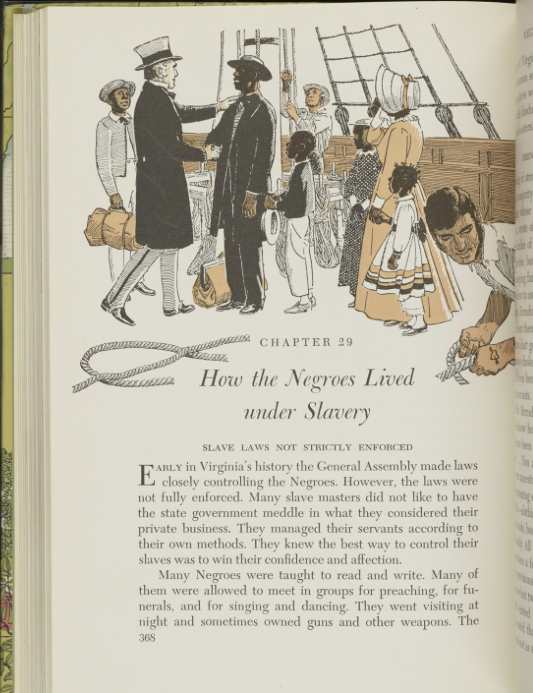

My fourth-grade history book, written and approved by the Virginia History and Textbook Commission, was published in 1957 and was taught in the state's public schools through the early 1970s. That text declared that 1619 was, owing to three important events, a "red letter" year for the Virginia colony. One was that the colonists were permitted to make their own laws. Another was that young English women immigrated to become wives of the colonists. And the the third was that "the first Negroes were brought from Africa."

The textbook went on: "There were about twenty of these Negroes. They were sold as servants to some of the planters. Soon other Negroes were brought to Virginia. They helped the planters do the work on their plantations." Later, my seventh grade history textbook asserted that the "regard that master and slaves had for each other made plantation life happy and prosperous" and that the "Negroes went about in a cheerful manner making a living for themselves and for those for whom they worked."

The book reported that it was regrettably necessary sometimes to "punish disobedient Negroes" by whipping them. But that was fine, it added, since "in those days whipping was also the usual method for correcting children." It further elaborated that most slaves did not long for freedom and thus "were not worried by the furious arguments going on between Northerners and Southerners over what should be done with them. In fact, they paid little attention to these arguments."

My 11th grade textbook infamously maintained that an enslaved person "did not work as hard as the average free laborer, since he did not have to worry about losing his job. In fact, the slave enjoyed what we might call comprehensive social security." In other words, Virginia's schoolchildren were taught that slavery was a safety net.

One of the authors of that 11th grade textbook, Marvin Schlegel, explained at a 1957 conference why he chose to portray the history of slavery in Virginia the way he did. "When it is necessary to discuss the Negro, he should be praised for those qualities which are approved by the whites, his loyalty to his master for example," he said. But "the realistic version" of history, he noted, would "put our ancestors in too severe a light."

After the end, in 1865, of what my public school history texts were pleased to call the War Between the States, civil equality for America's black citizens were embodied in the 13th,14th,and 15th amendments to the Constitution. But these promises were betrayed as Virginia and other Southern states erected a new version of their old racial caste system. Under the so-called Jim Crow laws, every white citizen was legally superior to every black citizen. The erosion of civil rights sped up after the Supreme Court's vile 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, which ratified a Louisiana law requiring that white and black railroad passengers ride in separate cars. The majority opinion, written by Associate Justice Henry Brown, rejected "the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority."

In a brilliant dissent, Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan pointed out that the court's majority opinion had now ratified "a power in the States, by sinister legislation, to interfere with the full enjoyment of the blessings of freedom to regulate civil rights, common to all citizens, upon the basis of race, and to place in a condition of legal inferiority a large body of American citizens." Harlan proved all too prescient: Virginia and other states quickly established an oppressive system of legal apartheid that, in the main, persisted even as the Martin Luther King was speaking in Washington. "Whites Only" signs were still pervasive throughout the South, limiting access to all sorts of public facilities and accommodations.

A 1947 report by the Civil Rights Commission recounted in gory detail how federal, state, and local governments regularly violated the civil rights of several minority groups, but chiefly those of African Americans. The report described lynching, widespread police brutality, and bureaucratic discrimination. It also highlighted how black citizens (and many poor white ones) were systematically denied the vote by means of poll taxes and unequally applied "understanding clauses" that required would-be voters to explain a state's constitution to the satisfaction of a registrar. As a result of this discrimination, the report estimated that only about 10 percent of potential voters in the seven poll-tax states participated in the presidential elections of 1944, as against 49 percent in the free-vote states. Even more egregious was the creation of "whites only" Democratic Party primaries in seven states.

The report concluded that "the separate but equal doctrine has failed," declaring that "it is inconsistent with the fundamental equalitarianism of the American way of life in that it marks groups with the brand of inferior status." Consequently, the commission recommended "the elimination of segregation, based on race, color, creed, or national origin, from American life." Shortly afterward, on July 26, 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, mandating the desegregation of the U.S. military.

The Civil Rights Commission's report and Truman's desegregation of the military alarmed segregationists. They were among the reasons Virginia's white leaders created the state's textbook commission in 1950.

Just two months before King spoke, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission issued its 1963 report. "In seven States," it noted, "the right to vote—the abridgment of which is clearly forbidden by the 15th amendment to the Constitution of the United States—is still denied to many citizens solely because of their race."

"There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, when will you be satisfied?" King said in his famous speech. His answer:

We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities.

We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: for whites only.

By the time I entered the fourth grade, the percentage of white Americans who agreed that black and white children should go to the same schools had essentially doubled from 32 percent in 1942 to 64 percent. (96 percent now do.) In a 1963 poll, more 60 percent of whites said that whites had the right to bar blacks from their neighborhoods. That fell to 15 percent by 1995, when the question was last asked.

In 1948, 30 states still had laws making it crime for black and white citizens to marry; today, thanks to the 1967 Supreme Court case Loving v. Virginia, it is legal everywhere. In 1958, only 4 percent of American adults approved of black-white marriages; now 94 percent do.

A year after King declared his dream that our country would soon "live out the true meaning of its creed," Congress finally enacted federal legislation aimed at dismantling the South's system of legally imposed and enforced racial apartheid. Such state and local laws made it illegal for businesses to accommodate both black and white customers even if they wanted to do so.

First, Congress passed the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination at places of public accommodation on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin. This overturned such regulations as a South Carolina ordinance that had mandated racially segregated eating areas in "any hotel, restaurant, cafe, eating house, boarding-house or similar establishment." That South Carolina law decreed that there must be a seating distance of at least 35 feet between white and black customers and that meals be served using clearly marked "separate eating utensils and separate dishes."

Congress then passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which eliminated "tests and devices," such as literacy tests and poll taxes, that had been used to prevent black citizens from successfully registering to vote. After its adoption, the percentage of blacks registered to vote in Virginia rose from 19 percent in 1956 to 46.9 percent in 1966. By 2020, 72.7 percent of Virginia's black residents were registered to vote.

Sixty years later, overt and legally enforced racial discrimination has receded. But even now, various state legislatures are attempting to enact racial gerrymandering to hem in the votes of their black citizens.

How history should be taught remains contentious in Virginia. Witness Gov. Glenn Youngkin's first executive order, which instructed K–12 public schools "to end the use of inherently divisive concepts." But the state's current history and social science standards of learning for the fourth grade explicitly include describing "the laws that established race-based enslavement in the colony" and "how the institution of slavery was the cause of the Civil War." Later in the year, fourth grade history classes will explain "the social and political events connected to disenfranchisement of African American voters in Virginia in the early 20th century, desegregation, court decisions, and Massive Resistance, with emphasis on the role of Virginians in the Supreme Court cases, including, but not limited to Brown v. Board of Education." In addition, students will learn about the political, social, and economic contributions of prominent black Virginians such as Maggie Walker, Oliver Hill, Sr., and Douglas Wilder.

Instead of teaching that slavery amounted to a kind of "comprehensive social security," 11th grade history will now discuss "the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the 1963 March on Washington, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965." Those 11th graders will also "evaluate the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., including "A Letter from a Birmingham Jail," civil disobedience, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the 'I Have a Dream' speech, and his assassination." This is all far better than the lessons inflicted on my peers and me.

Any glance at the state of America's prisons and public schools will reveal how much more must be done before all Americans enjoy fully equal rights. But 60 years after King's famous speech at the Lincoln Memorial, we can celebrate how much closer we are to his dream of rising from "the dark and desolate valley of segregation" and into "the sunlit path of racial justice."

The post Martin Luther King's Lofty Dream Turns 60 appeared first on Reason.com.