Martin Amis, whose dark and wry dissections of modern culture and its excesses helped to redefine the British literary scene in the 1980s, and who later explored subjects such as extremism under an image he cultivated as a truth-telling provocateur, has died aged 73.

Amis’s heavy doses of cultural criticism and misanthropic bite drew comparisons with the style of his father, Kingsley Amis, who won the Booker Prize in 1986 for his novel The Old Devils. The younger Amis found his voice as a savage reviewer of what he saw as modern society’s self-destructive tendencies and bottomless absurdities.

Amis’s so-called London trilogy – Money: A Suicide Note (1984), London Fields (1989) and The Information (1995) – was a tableau of greed, compromised morals, and a society asleep at the wheel. Critics hailed Amis as part of a new literary wave in Britain that included Salman Rushdie, Ian McEwan and Julian Barnes.

American writer Mira Stout, in a New York Times profile of Amis, lauded his “cement-hard observations of a seedy, queasy new Britain, part strip-joint, part Buckingham Palace”.

His style was kinetic and restless, weaving from satirical to comic to professorial. Human flaws such as vanity, selfishness and moral weakness abounded. In some ways, his writing foreshadowed the cacophony of the digital age and the scramble for a slice of instant celebrity. “Plots really matter only in thrillers,” he told The Paris Review. He sometimes referred to his books as “voice novels”, saying: “If the voice doesn’t work, you’re screwed.”

The London trilogy is something of a peep show, he said. “What I’ve tried to do is to create a high style to describe low things: the whole world of fast food, sex shows, nude mags,” Amis told The New York Times Book Review in 1985.

“I’m often accused of concentrating on the pungent, rebarbative side of life in my books, but I feel I’m rather sentimental about it,” he continued. “Anyone who reads the tabloid papers will rub up against much greater horrors than I describe.”

Amis’s creative point of reference was often regarded as Britain, but he found rich fodder in his long association with the United States. His 1986 collection of non-fiction essays, The Moronic Inferno, is a stranger-in-a-strange-land mediation on America, as if Alexis de Tocqueville had arrived and found a circus.

“Writing comes from silent anxiety, the stuff you don’t know you’re really brooding about, and when you start to write, you realise you have been brooding about it, but not consciously,” he told the Associated Press in 2012. “It’s terribly mysterious.”

Reviewers, however, at times saw his work as intending to make big statements but coming up short. Writing about The Pregnant Widow in 2010, The Washington Post’s Ron Charles called it a “nakedly autobiographical novel” of sex-obsessed college kids at an Italian castle in the summer of 1970. “The setting is exotic, the subject is erotic, but the story is necrotic,” wrote Charles.

After the publication of The Second Plane (2008), a collection of non-fiction and short stories on the 9/11 attacks and their aftermath, reviewer Leon Wieseltier wrote in The New York Times: “Amis’s clumsily mixed cocktail of rhetoric and rage can be eccentric, or worse.”

Amis finished 15 novels over the course of his career. His most recent, Inside Story (2020), was described as a “novelised autobiography” that included reminiscences of fellow writers and friends, including Christopher Hitchens and Saul Bellow.

In his memoir Experience (2000), Amis turned the lens on himself. He wrote about his father’s death in 1995, and recalled his first wife, American scholar Antonia Phillips, and their two sons. He also examined the life and legacy of his cousin, Lucy Partington, who was abducted and killed in 1974 by serial killers.

Last week, a film adaptation of his 2014 novel The Zone of Interest premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. The plot follows the family of a high-ranking SS officer, who live next door to Auschwitz.

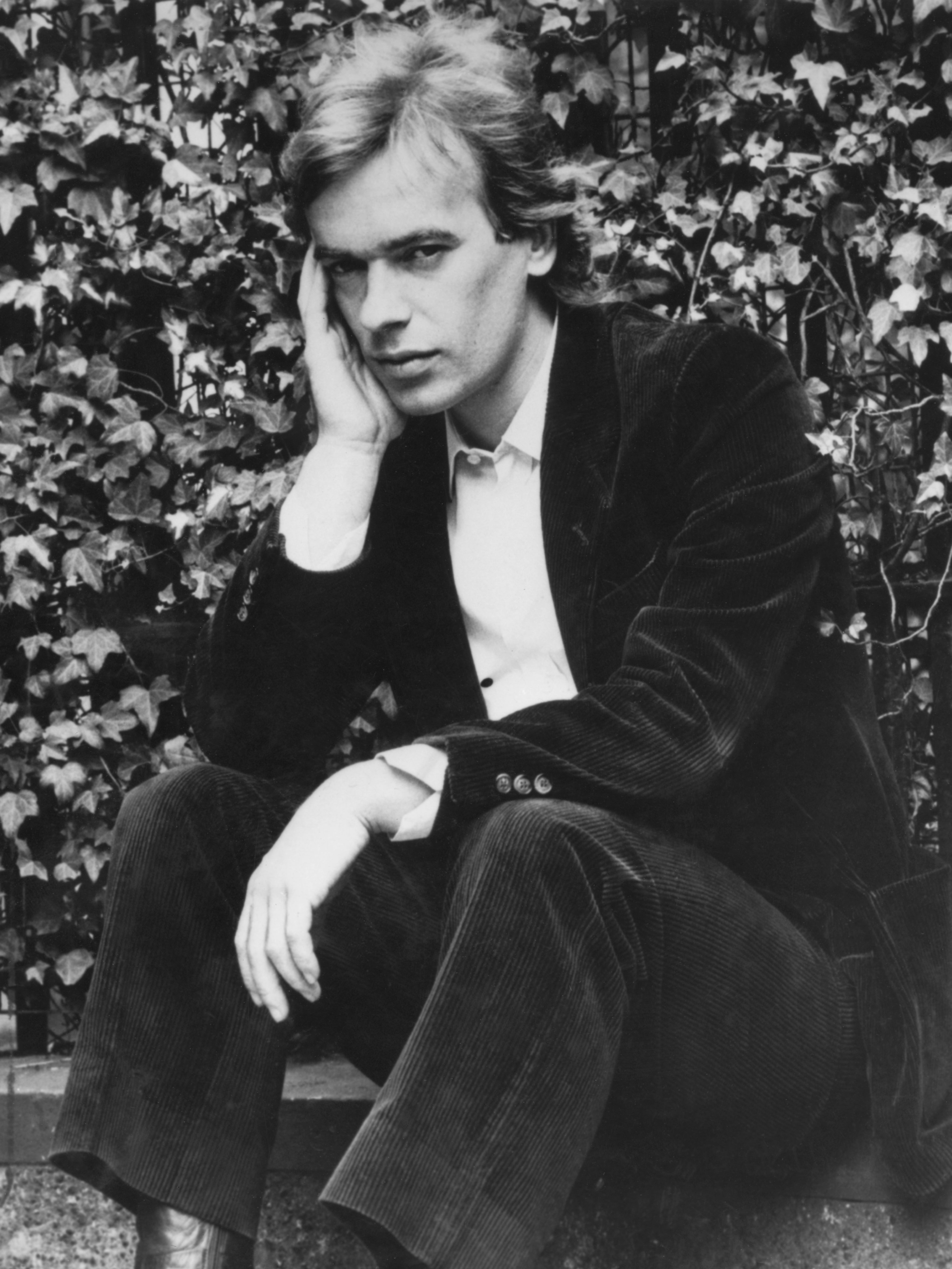

As a young literary star, Amis cultivated a fast-lane image: bigger, brasher, brazenly provocative. In a 1985 interview with The Washington Post, he put it all on full display.

He described the perverse pleasure of watching another writer get slammed by critics. “You know that feeling when one of your peers goes down,” he said. “It’s a real buzz. As Gore Vidal said, ‘It’s not enough to succeed. Others must fail.’”

He took a drag on a cigarette. “We all pretend that we’re quite modest,” he said, “but you can’t be a puppy as a writer.”

Martin Louis Amis was born in Oxford on 25 August 1949, and moved frequently as the marriage of his father Kingsley and his mother, Hilary Bardwell, began to come apart. He spent the academic year of 1959-60 in Princeton, New Jersey, where his father was lecturing and working after the publication five years previously of his breakthrough work, the comic masterpiece Lucky Jim (1954).

“America excited and frightened me,” Amis wrote decades later, “and has continued to do so.”

His parents divorced when he was 12. He said it had left him devastated, but he also credited his stepmother, novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard, for encouraging him to follow the literary path of his father.

“I’d be in a very different position now if my father had been a schoolteacher,” Amis told The Sunday Times in 2014. “I’ve been delegitimised by heredity. In the 1970s, people were sympathetic to me being the son of a novelist. They’re not at all sympathetic now, because it looks like cronyism.

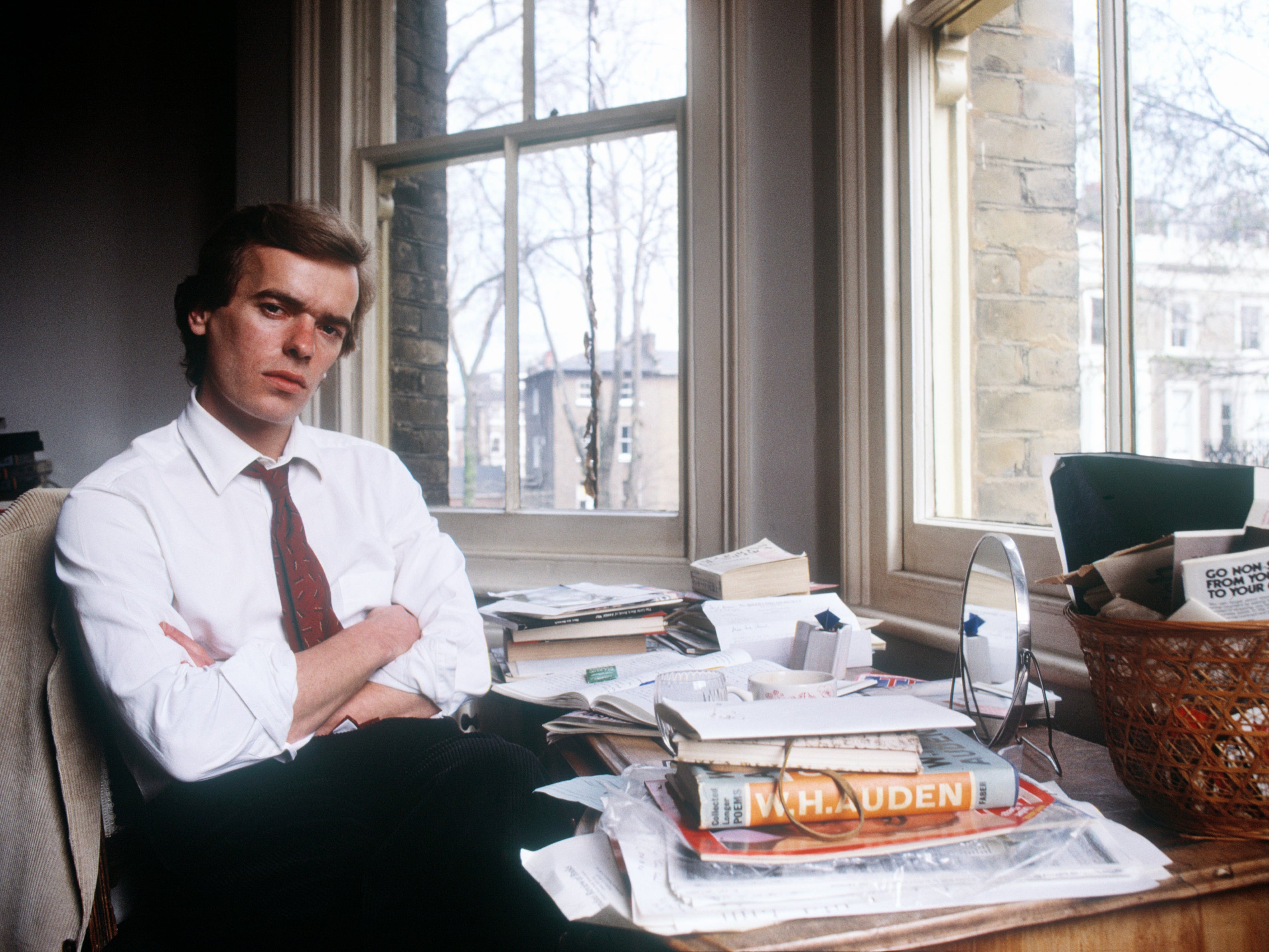

Amis graduated in 1971 from Exeter College at the University of Oxford. His first novel, The Rachel Papers, a coming-of-age tale of clumsy sex amid the temptations and changes of the 1960s, was published in 1973 while he was an editorial assistant at The Times Literary Supplement in London.

He followed it with a darkly comic novel, Dead Babies (1975), recounting a story of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll over one raucous weekend, and Success (1978), about rivalries and clashing values in a family.

He was literary editor of the New Statesman between 1977 and 1979 as he built relationships with rising literary talents, including an enduring friendship with the mercurial Hitchens – even as they publicly bickered over politics and the state of the world. When Hitchens died in 2011, Amis delivered his eulogy.

Amis could also bring about self-induced tumult. He was accused of Islamophobia in 2006 after saying that the Muslim community “will have to suffer” until it “gets its house in order”. He later apologised.

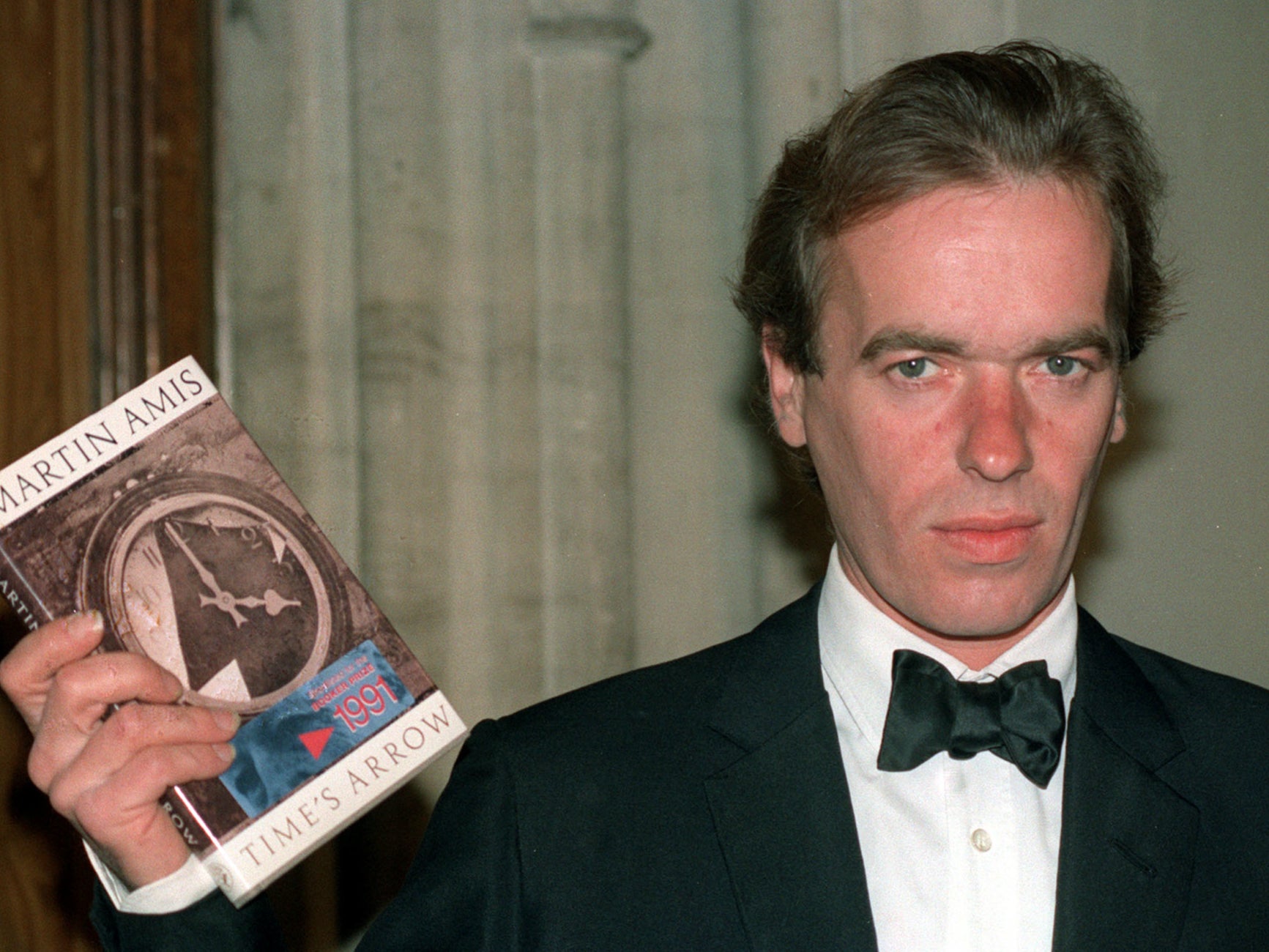

Amis was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for his 1991 novel Time’s Arrow, the life story of a fictional Nazi war criminal told in reverse chronological order.

Amis’s marriage to Phillips ended in divorce. He married the writer Isabel Fonseca in 1996. Survivors include Amis’s two children from his first marriage, two children with Fonseca, and a daughter from another relationship.

He left Britain in 2012 with his wife in order to be closer to her parents.

As Amis grew older, he cast aside some of his caustic detachment. It was diluted with some self-appraising candour. No matter how snarky he may have seemed in earlier decades, he confided in Inside Story, the stories only worked if they were grounded in compassion and empathy.

“This is literature’s dewy little secret,” Amis wrote. “Its energy is the energy of love.”

Martin Amis, author and writer, born 25 August 1949, died 19 May 2023

© Washington Post