A year and a half after the end of its mission, NASA’s InSight Mars lander may have just helped scientists find enough water to fill an ocean.

Deep beneath NASA’s InSight lander (RIP InSight), an ocean’s worth of liquid water may be trapped in rocky fissures, suggests a recent study of data recorded during more than 1,300 Marsquakes. If University of California, San Diego, geologist Vashan Wright and his colleagues are right, then Mars may be hiding underground reservoirs of water larger than the planet’s ancient, now-vanished, oceans. That could change how we search for traces of life on Mars, as well as how future Mars missions could supply themselves with water, rocket fuel, and oxygen to breathe.

Wright and his colleagues published their work in the journal Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences.

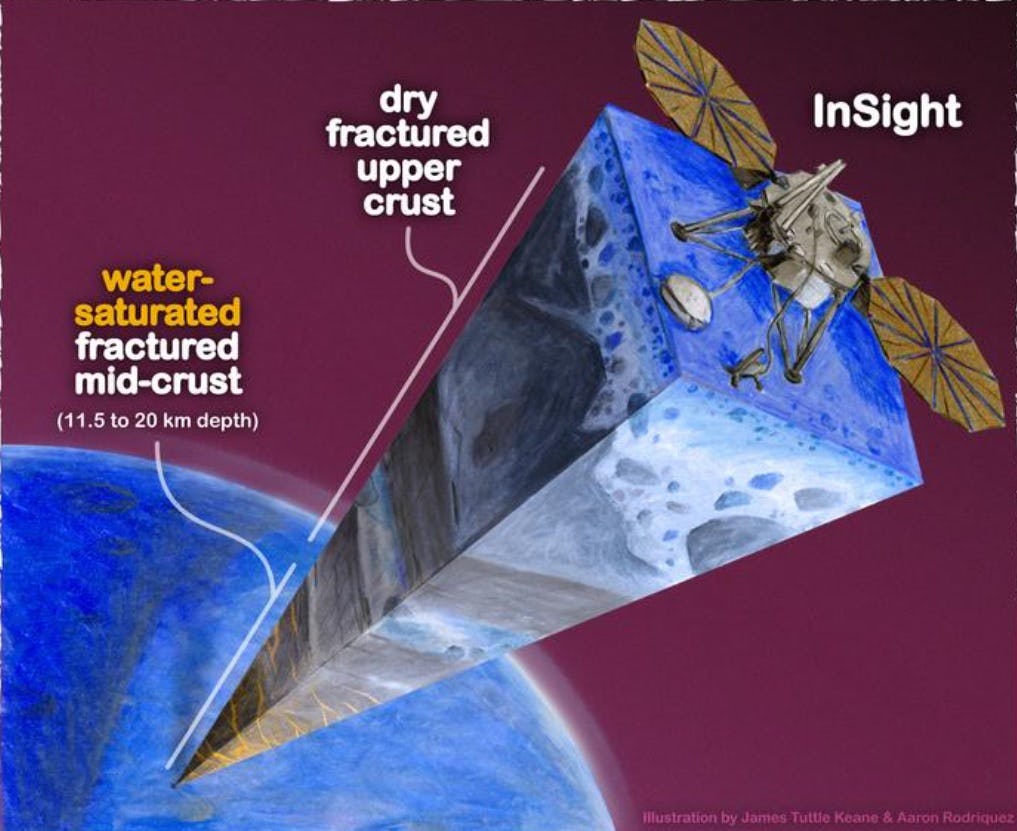

Reservoirs 7 Miles Deep

Wright and his colleagues recently simulated how seismic waves would move through different types of rock deep in the Martian crust and how fast those waves would travel if pores and cracks in the rock were filled with ice or liquid water. They compared those simulations to InSight’s measurement of actual seismic waves, as well as other missions’ measurements of the planet’s gravity and shape. In the end, the model that best matched the actual data was a deep layer of igneous rock (cooled, solidified magma), riddled with cracks and fissures that had formed as the magma cooled. And according to the researchers’ models, those cracks should be filled with liquid water.

The water-filled rock layer lies 7 to 12 miles beneath where InSight sits on the surface of Elysium Planitia, a wide swath of plain on the equator of Mars. The layers of rock closest to the surface are dry, based on the models, but about 7 miles down, cracks in the rock are filled with water. Wright and his colleagues aren’t sure if the deep crust beneath the rest of the planet looks the same, but if it does, then there could be more than an ocean’s worth of water hidden in the depths of the Martian underground, in cracks in long-ago-cooled magma.

Lost Water

Based on a mixture of geology and climate models, we’re pretty sure that Mars was a much warmer, wetter place 3 billion years ago. More than a third of the planet lay beneath ocean waves, and lakes and rivers watered much of the rest of the surface. But then everything changed: the spinning liquid core that powered Mars’s magnetic field slowly cooled. The magnetic field, which had shielded Mars from the Sun’s constant barrage of electrically-charged particles sputtered and died. Solar wind stripped away most of the Martian atmosphere, leaving behind an incredibly thin layer of mostly carbon dioxide.

When Mars lost its atmosphere, most of the water on its surface probably also evaporated because it would have boiled immediately in such incredibly low pressure (the air pressure on Mars’s surface today is less than 1 percent of Earth’s air pressure at sea level).

But Wright and his colleagues’ findings suggest the story may not be that simple. Mars may not have lost most of its water after all. The amount of water that Wright and his colleagues calculate could lie in the depths of the Martian crust means that “Mars’s crust need not have lost most of its water via atmospheric escape,” as the researchers write in their recent paper.

What’s Next?

More simulations, taking into account the possibility of whole oceans of water hidden miles beneath the surface, could reveal new information about Mars’s sparse but dynamic water cycle. The presence of water hidden in the cracks of deeply-buried rock could also suggest new places to search for evidence of ancient, or even modern, life on Mars. And if future Mars missions can drill deep enough wells, they may have a ready source of water for thirsty crews.