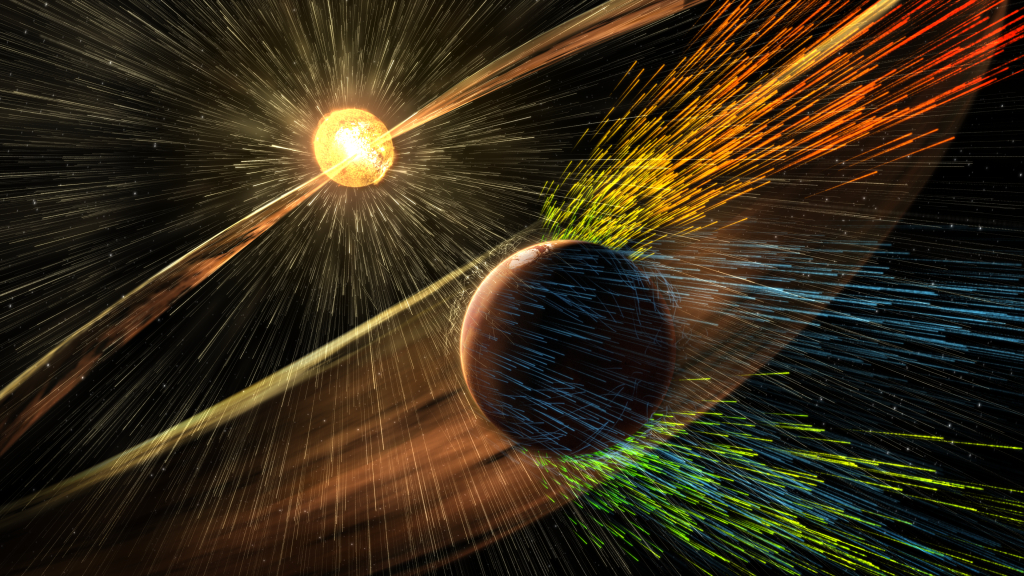

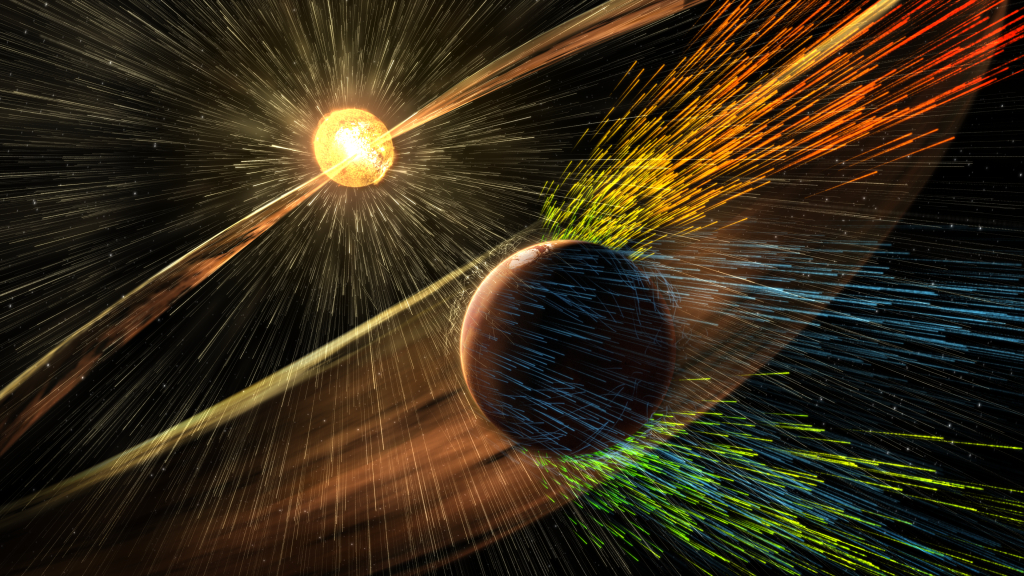

Mars' atmosphere, once as thick as if not thicker than Earth's today, is leaking into space.

About 0.25 lbs of Mars' atmosphere (0.11 kg) is pushed away every second by the incessant solar wind, the speedy stream of charged particles routinely blasted from the sun which pervade the solar system and even reach beyond Pluto.

But for a rare two days last December, some of that wind went away. Its sudden and dramatic disappearance caused the atmosphere on Mars' sun-facing side to swell by nearly four times its usual size — from its usual 497 miles (800 km) to over 1,864 miles (3,000 km). The peculiar event was recorded by a NASA orbiter named MAVEN (short for Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution) which has been observing both Mars's atmosphere and its response to the sun's behavior since 2014. MAVEN's data showed other aspects of the Martian system, including the tear drop-shaped magnetosphere, the bow shock and the ionosphere expanded similarly.

"We're really off the charts here," Jasper Halekas, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Iowa and a member of the MAVEN team, said on Monday (Dec. 11) at the AGU conference being held this week in California and online. "This is something that we haven't seen at Mars before with MAVEN."

Related: Lost in Space: How Mars' Atmosphere Evaporated Away

The atypical episode — the first in nearly a decade of MAVEN's career — occurred after a fast-moving region of a solar wind overtook its slower counterpart and swept up the latter's material, leaving behind a sparse region. The emptied storm reached Mars on Dec. 25, 2022, giving scientists a thrilling front-row seat to watch the planet's atmosphere balloon out, the way it might have been if it were circling a less 'windy' star.

"This was a Christmas present for us," said Halekas, who is leading a new study reporting this event. "Nature set up this perfect science experiment."

With MAVEN's data of the unexpected dynamics on Mars, Halekas and his colleagues studied how extreme solar events — and their absence — influence the planet's atmosphere, an insight valuable to understanding its evolution. The findings also have implications for our understanding of Earth-like planets outside our solar system and how they interact with their host stars, the team shared on Monday.

"We could look under the hood at what physics is going on, how the dynamics are working and really get a sense of those details," said MAVEN team member Skylar Shaver of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics in Boulder.

Two days after the almost-vacant storm passed Mars, the atmosphere around the Red Planet settled down to its original state once again, but not before bouncing a little like a jiggling plate of Jell-O. A similar storm struck Earth in 1999, when our planet's atmosphere grew to five times its normal size. But there aren't often orbiting spacecraft positioned as well as MAVEN is now to study such events, the New Atlas reported.

Shannon Curry, the principal investigator for the MAVEN mission, suspects events like this were common during Mars' early evolution 3 to 4 billion years ago, when our sun was more fiery than it is now and perhaps blasted out storms once a week or even every day. Such extreme events were likely responsible for parching the Red Planet, a world scientists presume once hosted liquid water and offered conditions friendly toward life. Extrapolating the latest MAVEN data to study Mars' evolution through time could shed light on how much its atmosphere eroded away and how fast the planet dried up, Curry said.

Curry added events like this may occur multiple times in the next two years as the sun's activity climbs to its peak, expected to occur in July 2025 if not late next year.