According to the U.S. research and consulting firm CB Insights, most entrepreneurs fail because they lack sufficient financing. The second reason they fail is because the market for their product is too small.

Yet many entrepreneurs and coaching professionals continue to reject the market research phase in favour of a “fail fast, pivot quickly” approach. Launching companies this way — even if it means having to adapt to customer feedback later — is very trendy, especially in the world of startups.

However, as the bitter experience of Canadian entrepreneur Tom Zaragoza demonstrates, “learning by doing” is no guarantee that a business will gain traction in the marketplace. In 2017, after months of effort, Zaragoza launched his site Gymlisted to connect private gyms with users, only to find out that there was no demand for such a service.

Through my activities as a professor in entrepreneurial marketing, I unfortunately meet an increasing number of entrepreneurs who are convinced they have the idea of the century, but who do not take time to study the market in a structured way. Market research remains an essential step for entrepreneurs for the simple reason that if the owner is not a market expert, who is?

Two misconceptions about market research

Contrary to the story about the intuitive and visionary entrepreneur, and in a context where modern society applauds action over reflection, it turns out that market research is both essential and relevant — as long as two misconceptions that work against its adoption are removed.

First misconception: Market research is a linear and rational process that is not compatible with a company’s launch phase.

In reality, it is a set of methods and tools, the goal of which is to create a continuous learning loop by alternating phases of reflection with phases of experimentation. Whatever the size of the company, the approach is much more iterative (achieved through repetition), inductive and diversified than one might think.

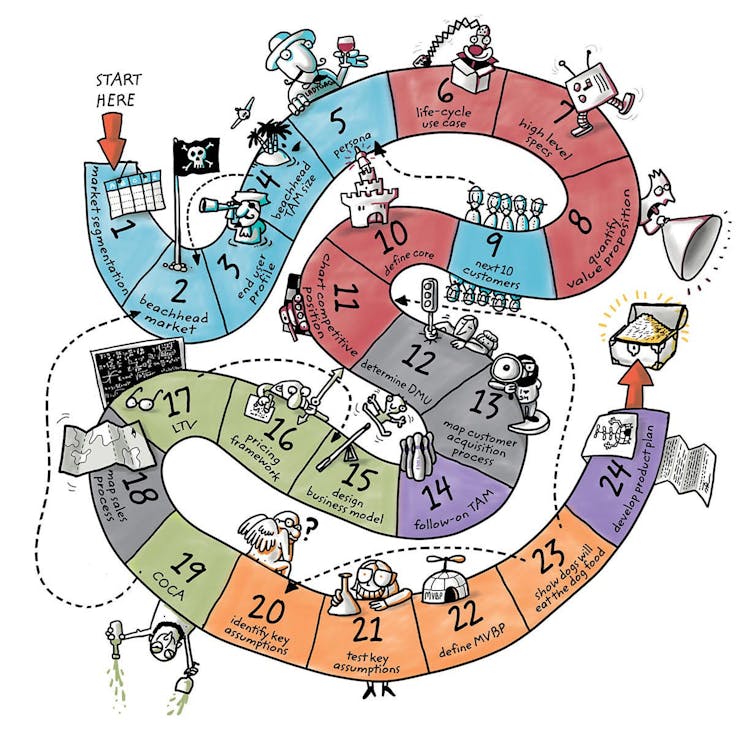

As demonstrated by the “disciplined approach” proposed by Bill Aulet, a professor at MIT, it is actually possible to study a market in a way that is structured and agile. The 24-step process starts with the study of the market fundamentals, an essential first step to understand the market structure and, above all, the different customer segments. Once the target customer is identified, the process unfolds by moving back and forth frequently between research and field studies.

Second misconception: Market research is simply about having large samples answer questionnaires.

The truth is, surveys are not a substitute for market research. Contrary to what some business sites advise, a good survey involves using complex methods that require specialized knowledge. The use of free online solutions, such as Google Forms, by inexperienced entrepreneurs often produces biased results that may not be very useful.

In view of these two misconceptions, it would be more appropriate to use the term “market intelligence,” which better translates the two key steps of a pragmatic and agile process adapted to the context of creation.

The two key steps to develop good market intelligence

Step 1: Do secondary market research to know your market

Secondary market research involves exploiting all existing knowledge.

A quick and efficient way to do this is to contact organizations such as professional associations, sector committees or even chambers of commerce. These institutions have the mission of collecting, synthesizing and making accessible relevant and credible information on a given sector or market, often at a very reasonable cost.

This approach allows entrepreneurs to quickly acquire the knowledge they need to start structuring the first hypotheses of their business model: What are the different customer profiles? What are their expectations and buying habits? What are the competing offers already on the market?

Step 2: Conduct qualitative studies to validate and adjust your business model.

The next step involves testing and exploring the marketplace on the ground by using qualitative methods. This type of study takes the form of individual or group interviews, or even simple observations, and makes it possible to deepen the hypotheses put forward following the research phase by directly interviewing those in the field.

Take the example of the UNIQ Hotel, an “ephemeral” accommodation launched in 2020.

Initially, studying the reports of the Tourism Intelligence Network of the Transat Chair of Tourism at the Université du Québec à Montreal and those of Camping Québec showed that this product might interest those who liked “glamping” and wanted both nature and comfort. Indeed, UNIQ offers yurts that can be set up and dismantled in different locations.

During the second phase, it makes sense to do individual or group interviews to understand the customer, their habits, their expectations and any possible obstacles.

This exploration phase makes it possible to understand which services are essential and which booking methods are commonly used.

This type of qualitative research would be an important step in completing the value proposition design, a tool that helps illustrate why the idea will meet the market’s expectations. The information also makes it possible to draw up a precise profile of the expected clientele using a “buyer persona,” a method for summarizing the main characteristics of future buyers.

Once this exploration phase is complete, one can wrap up with a test to ensure that there is demand for this type of accommodation. This can be done by applying concept testing. This simple and inexpensive process consists of submitting a printed or video description of the proposal to the target clientele to study their reactions and their level of intention to make a purchase.

These few good practices do not cover everything, and not all market research methods are applied to every creative context. But as many scientific studies have shown, knowing your market is a key factor of success for any company.

Philippe Massiera does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.