Sometimes, late at night, when Mario Cristobal is leaving the Miami football complex, he drives toward Kindred Hospital, a long-term acute-care center. Before arriving, he often realizes his mistake and wheels around toward his family’s home near campus.

“It’s old habit,” he says. For more than three months, Clara Cristobal lay intubated in a hospital bed, in and out of consciousness, unable to speak. Her illness coincided with her youngest son realizing a dream—accepting the head coaching job at Miami last December, a Cuban American captaining his hometown team’s football program.

While he toiled away putting his plans in place to revive one of college football’s lost brands, Cristobal spent early mornings and late nights at his mother’s bedside. He would play videos for her. He would talk to her, hold her hand, brush her hair. She’d smile at times, even squeeze his fingers.

“At the end,” Cristobal says, “she started to blow kisses.” Her final goodbye, at age 81, came March 4.

“She went knowing that he was home,” says Luis Cristobal Jr., Mario’s older brother. “She got to know that. She was happy.”

Alexander Aguiar/Sports Illustrated

If anything, Mario’s move from Oregon to Miami is one of family. It is one of home and heart. Few would be better suited for such a revival project than a 51-year-old coach at the top of his craft—a bilingual, Miami-bred man who grew up blocks from the university’s campus, played for the Hurricanes and began his coaching career there.

Is this really happening?

Está sucediendo esto realmente?

Cristobal returned to resurrect a program whose most recent national championship came 20 years and five coaches ago. He is back to save the Hurricanes.

“Miami has always been what I am. . . . This is the only place in the world where I don’t need a GPS,” he says. “The fact is, I need to be at Miami, and Miami needs me.”

During a segment on ESPN’s College GameDay last September, analyst Kirk Herbstreit urged Miami to get serious about its investment in football. The 70-second clip went viral, and the school’s most powerful people quickly sprung into action, perhaps out of embarrassment.

“Kirk helped us get to a tipping point,” says Rudy Fernandez, Miami’s executive vice president for external affairs and strategic initiatives, chief of staff, and the man put in charge of the football team’s overhaul. “The president and the board started giving serious thought to, ‘How do we fix UM football?’”

Part of the answer was replacing athletic director Blake James and coach Manny Diaz with a pair of high-profile hires—Dan Radakovich, one of the architects of Clemson’s football dynasty, and Cristobal, luring each to Miami with hefty salary pools and the promise of multimillion dollar facility upgrades. The hires, made within days of each other, sent the message that Miami was trying to get back.

It also made one particular figure uncomfortable. “I wasn’t trying to get Blake fired or Manny fired,” Herbstreit says. “I was really talking more to the people who spend money and where the money needs to go.”

Before Cristobal signed his contract, a plethora of budgetary items were approved. To start, the largest coaching staff salary pool in school history at $20 million a year. The price tag doubles last year’s staff pool, says Radakovich—$8 million going to Cristobal, $7.5 million for his on-field and strength staffs and $5 million for support staff members. In addition, more than $100,000 was spent on strength and conditioning equipment, recruiting budgets were significantly increased, and plans for a new football facility, estimated at $150 million, were launched.

Sam Navarro/USA Today Sports

It is all meant to lift the program out of what’s been a two-decade hole, a slide that coincided with the internet boom (no more hiding South Florida recruits from the rest of the country) and other schools surpassing the Hurricanes in resources. “Obviously,” says Cristobal, “we are behind.”

A full generation has seen a college football landscape without a relevant Miami impacting it. The school “accepted mediocrity,” says Jose Mas, a Cuban American tech CEO, Miami booster and high school classmate of Cristobal whose MasTec company is worth more than $7 billion. Miami was one of the last major college football brands not to have an indoor practice facility until former coach Mark Richt led a $40 million fundraising effort to get one built, and the field still isn’t at full length.

“Miami had such a strong run—five national championships in a 20-year period— that after all the success, they’re like ‘Why build something new? We’ve won without it,’” says Richt, who coached the team from 2016 to ’18. “There were a lot of things they were behind on or didn’t have in place, period.”

Radakovich is in the midst of an evaluation of the athletic department and says there are unique hurdles at Miami that other schools don’t face. It doesn’t have the football attendance and living alumni of many of its powerhouse peers. The undergraduate enrollment is 11,000, and season-ticket sales, while having spiked with Cristobal’s hire, are in the 30,000s.

The university is hurt financially by not having its own football stadium, instead playing some 25 miles from campus at Hard Rock Stadium. They split ticket, concession and parking revenue with the stadium, owned by Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross. Normally, a university’s main source of revenue comes from donations connected to season-ticket sales. Miami typically receives about $10 million in donations each year, Radakovich says—a strikingly low number compared to his former employer, Clemson, which raised $61 million in donations in 2021.

“There are challenges related to the dollars,” Radakovich says, “but there is money here.”

Some of the money issues stretch back to the university’s launch of a health care system that for years operated at a deficit, says Fernandez. “That was problematic. Investing in athletics was not the priority at that point.”

Now, however, that same health system is incredibly profitable. According to 2019 tax returns reviewed by the Miami Herald, the UHealth System generated about $300 million in profit, much of which was pumped back into the university. Like many athletic departments, revenue from Miami’s football program subsidizes its other sports. Fernandez says only four of its 17 teams have the attendance ability to produce any revenue, and three of the four struggle to be profitable.

The theory: A strong investment in football leads to winning football teams, which in turn buoys the entire athletic department and university. Of the school’s three verticals—higher education, health care and athletics—the third impacts “how the other two are seen,” Fernandez says.

“Once you understand the finances, we needed to invest in football or get out of the business of major athletics,” he adds. “Not get out of football, but athletics.”

About three miles from the Miami campus, adjacent to a strip mall of stores with barred windows and signs in Spanish, is a single-floor home with clay-colored walls and a tiled roof.

This is where Luis Sr. and Clara Cristobal raised two street-fighting sons in Coral Terrace, a neighborhood where their home was one of the few safe from robberies and vandalism. In high school, Luis grew to 6' 3", 240 pounds, and Mario was 6' 4", 230 pounds. No one messed with the Cristobals. Luis says Mario was once “one of the most dangerous men in Miami” given his skill in jujitsu, routinely forcing opponents into submission at local dojos. Luis recalls how Mario once witnessed a robbery, chased down the perpetrator and, after catching him, showed how good he was at the Brazilian martial art.

Luis Sr. and Clara separately fled Fidel Castro’s communist regime in the 1960s, not long after Luis Sr. was incarcerated as a political prisoner in Cuba. They met in Miami and spoke only Spanish—the first language of their sons as well. Luis Jr. and Mario learned English from watching The Three Stooges and The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends.

Luis Sr., who died in ’96, opened a car battery shop, and Clara worked as a clerk. They instilled a relentless work ethic in their boys, along with strong roots in their Catholic faith and a commitment to education.

“My only regret is neither of my parents got to see a free Cuba,” Luis Jr. says. He declined to detail his parents’ plights on the island except to say, “They suffered greatly.”

The pain runs deep. Clara once told Mario that if he ever visited Cuba, “I’ll turn over in the grave and slap your ass.”

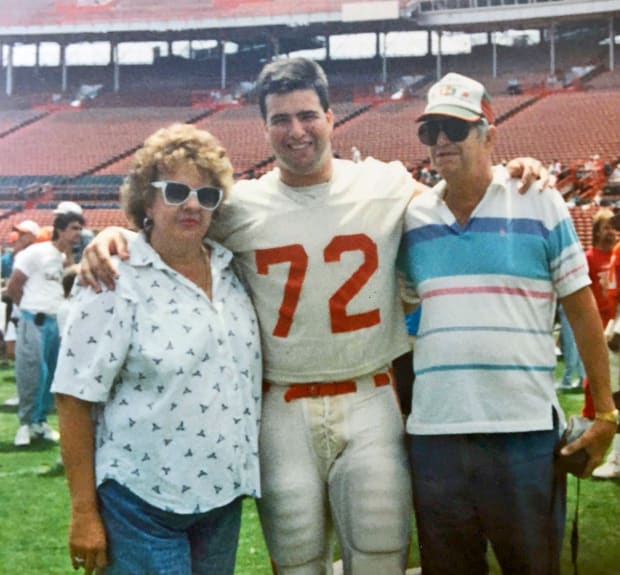

The Cristobals’ pride in their adopted hometown and college team played significant roles in Mario’s accepting the job. As a young boy, he pedaled his bike onto campus to watch Hurricanes greats of the 1980s practice on the same fields now visible through his office window. Both brothers were offensive linemen for the U—Luis from ’87 to ’90 (winning one national title), and Mario from ’89 to’92 (two championships).

In an interview for his first coaching job, a graduate assistant spot at Miami, then coach Butch Davis asked young Mario about his long-term goal in life. Mario pointed at Davis, “To be sitting in that chair.” Since returning to Miami, he has rediscovered his home. He stops into famed restaurant Versailles to hear Cuban gossip from the locals.

He swings over to Casa Juancho for his favorite Cuban meal. He fishes off Miami Beach bridges with his two sons, Mario Mateo and Rocco, just like his father did with him and Luis.

“I’ve been away for so long, I forgot how much I loved it here,” Mario says. “I f------ love this place, ya know?”

And yet, when offered the job, Cristobal deliberated over the decision for two days. He circled 2022 as his best Oregon team, when his first signing class would mature to seniors. He had evolved into a self-proclaimed West Coast small-town guy. He led the Ducks to three straight appearances in the Pac-12 title game, two of which they won. With Cristobal still deliberating over his decision, Mas and a small group flew six hours to Eugene on a private jet to assure they had secured their man. “You guys didn’t have to fly all the way out here,” Cristobal told Mas when they arrived.

Mas shot back, “I had to make sure your ass was on the damn plane.”

Courtesy of the Cristobal Family

Now, Cristobal is determined to return Miami back to a program whose championships brought together a diverse group of people, many of them immigrants.

“The U is the one thing that unites this city,” Mas says. “Every city has a sports team it rallies behind. Here, the Dolphins came, then the Heat, then the Marlins, but the U has been here all along.”

The intense decision-making process is indicative of Cristobal’s equally intense, obsessive personality. One person close to Cristobal describes the coach as part Saban, part Ed Orgeron and part Scarface. Some within the coaching ranks say he is hard to work for—but, for him, that just means those people aren’t working hard enough.

“He doesn’t allow anyone to be complacent,” says Aaron Feld, the strength coach Cristobal brought in from Oregon.

Watch college football with fuboTV. Start free trial today.

Cristobal’s intensity has also carried over to his new job. During a call in July, his eyes were trained on an iPhone that was streaming the commitment announcement of prized prospect Raul Aguirre. The linebacker sat at a table before a half-dozen hats, including Miami, Ohio State, Alabama and his home state school, Georgia. When the video ended with a Miami hat resting on Aguirre’s head, Cristobal dramatically raised his hands in front of his face, interlocking his thumbs to form an unmistakable signal. “The U,” he says.

It was one small victory among a collection of the others necessary to achieving his ultimate goal: wake this sleeping giant. And Cristobal says one way to resurrect the once-proud program is acquiring talent. “You can’t out-coach recruiting,” says Jason Taylor, the NFL Hall of Famer who is now a defensive analyst here.

When Cristobal took over last December, the Hurricanes’ commitment class ranked around 70th in the 247Sports recruiting rankings. They finished 16th. Since then, it’s been a wave of high-profile recruiting wins for UM’s 2023 class: Francis Mauigoa, the top offensive tackle in the country, and Riley Williams, the second-best tight end, as well as three more players within the top 10 at their positions.

The Hurricanes are barreling toward what could be their first top-five signing class since they finished No. 1 in 2008. Coinciding with Cristobal’s arrival, billionaire booster John Ruiz has spent $7 million this year on name, image and likeness deals, at Miami and beyond—dollars that have drawn an official inquiry by the NCAA. But success goes beyond cash deals.

Cristobal is in the process of aligning with the South Florida community, repairing bridges and rekindling relationships. Within Miami’s football facility, the coach has no time for gimmicks, removing the notorious turnover chains, the gaudy in-game jewelry worn by players who recovered a fumble or picked off a pass. Cristobal normally beats everyone to the building before 5 a.m. and is the last one out at 11 p.m. He does this six days a week and expects the same dedication from his staff and players. Cristobal’s practices are intense, akin to preseason camp.

“We train hard as s---,” says Feld, “and we practice hard as s---, too.”

In Cristobal’s first two games, the Hurricanes trounced lesser competition in Bethune-Cookman and Southern Miss by a combined score of 100-30. Test No. 3 will be a little different. The No. 13-ranked Hurricanes (2–0) meet No. 24 Texas A&M (1–1) at Kyle Field—and although Appalachian State’s upset of the Aggies last week zapped some buzz from the matchup, the SEC-vs.-ACC clash will be Cristobal’s first real challenge as Miami’s leader.

Many believe he has the team to challenge for this season’s league title. At quarterback, the Hurricanes have the ACC Rookie of the Year, Tyler Van Dyke. There is 6' 5", 245-pound Will Mallory, emerging young safety James Williams and a half dozen transfer-portal acquisitions who started at Power 5 clubs a year ago, such as Henry Parrish (Ole Miss), Darrell Jackson (Maryland) and Akheem Mesidor (West Virginia). Cristobal’s staff includes reigning Broyles Award winner Josh Gattis at offensive coordinator, longtime SEC coordinator Kevin Steele leading the defense and Charlie Strong coaching linebackers.

“It appears from the outside that the university is committing more to the program than maybe ever,” says Butch Davis, coach at UM from 1995 to 2000. “The ability and potential with Miami is off the charts.”

Mario Cristobal didn’t get a chance to say one last goodbye to his mother. Doctors performed an emergency intubation on Clara on Nov. 27 while her son led his Oregon team’s walkthrough before their rivalry game against Oregon State. A staff member rushed onto the practice field to pull him away. He got to the phone too late.

“We were in the room and holding off the doctors,” Luis recalls. “ ‘Give me one more minute!’ I’m watching her fade in front of me. I’m talking to her, and the doctor told me, ‘We’ve got to do this now or else.’ ”

Mario lives with that to this day, unable to have a final moment with the woman who fled Cuba and worked until she was 79. “It’s hard,” he says. “I never made it to the phone.”

He did make it home, however. Above his desk in his office, not far from where his mother died, Cristobal has framed photos of the four coaches who have won national titles at Miami: Howard Schnellenberger, Jimmy Johnson, Dennis Erickson and Larry Coker. What other school has had four coaches win national championships in a 20-year span?

“None,” he says. “Football here is life. I feel like I need to be around that. I feel like I worked my whole life to be the head coach at Miami. Everything is in place to make this a perennial power.”

Only time will tell whether a fifth framed picture will be added to that wall, the face of Clara Cristobal’s youngest son, the pride of Miami and now its beacon of hope. “I think it’s a given: He’s going to win a national title,” Luis says. “I’m biased because he’s my brother, but the kid is a badass. He’s never lost that edge.”