As the world struggles to decarbonise, it’s becoming increasingly clear we’ll need to both rapidly reduce emissions and actively remove carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere. The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report considered 230 pathways to keep global warming below 1.5°C. All required CO₂ removal.

Some of the most promising CO₂ removal technologies receiving government funding in the United States, United Kingdom and Australia seek to increase the massive carbon storage potential of the ocean. These include fertilising tiny plants and tweaking ocean chemistry.

Ocean-based approaches are gaining popularity because they could potentially store carbon for a tenth of the cost of “direct air capture”, where CO₂ is sucked from the air with energy-intensive machinery.

But the marine carbon cycle is much harder to predict. Scientists must unravel the many complex natural processes that could alter the efficiency, efficacy and safety of ocean-based CO₂ removal before it can go ahead.

In our new research, we highlight a surprisingly important mechanism that had previously been overlooked. If CO₂ removal techniques change the appetite of tiny animals at the base of the food chain, that could dramatically change how much carbon is actually stored.

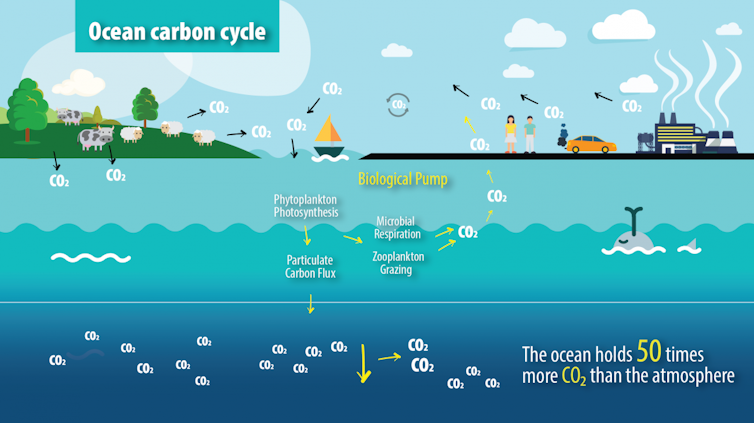

Plankton dominate the carbon pump

Tiny marine life forms called plankton play a huge role in ocean carbon cycling. These microscopic organisms drift on the ocean currents, moving captured carbon throughout the seas.

Like plants on land, phytoplankton use sunlight and CO₂ to grow through photosynthesis.

Zooplankton, on the other hand, are tiny animals that mostly eat phytoplankton. They come in many shapes and sizes. If you put them in a lineup, you might think they came from different planets.

Across all this diversity, zooplankton have very different appetites. The hungrier they are, they faster they eat.

Uneaten phytoplankton – and zooplankton poo – can sink to great depths, keeping carbon locked away from the atmosphere for centuries. Some even sink to the seafloor, eventually transforming into fossil fuels.

This transfer of carbon from the atmosphere to the ocean is known as the “biological pump”. It keeps hundreds of billions of tonnes of carbon in the ocean and out of the atmosphere. That translates to about 400ppm CO₂ and 5°C of cooling!

Picky eaters

In our new research we wanted to better understand how zooplankton appetites influence the biological pump.

First we had to work out how zooplankton appetites differ across the ocean.

We used a computer model to simulate the seasonal cycle of phytoplankton population growth. This is based on the balance of reproduction and death. The model simulates reproduction really well.

Zooplankton appetites largely determine the death rate. But the model’s not so good at simulating death rates, because it doesn’t have enough information about zooplankton appetites.

So we tested dozens of different appetites and then checked our results against real-world data.

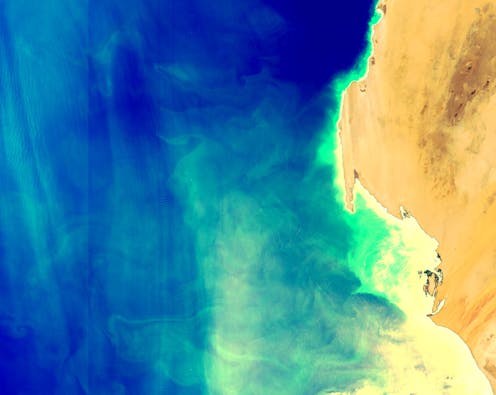

To get global observations of phytoplankton seasonal cycles without a fleet of ships, we used satellite data. This is possible even though phytoplankton are tiny, because their light-catching pigments are visible from space.

We ran the model in more than 30,000 locations and found zooplankton appetites vary enormously. That means all those different types of zooplankton are not spread evenly across the ocean. They appear to gather around their favourite types of prey.

In our latest research, we show how this diversity influences the biological pump.

We compared two models, one with just two types of zooplankton and another with an unlimited number of zooplankton – each with different appetites, all individually tuned to their unique environment.

We found including realistic zooplankton diversity reduced the strength of the biological pump by a billion tonnes of carbon every year. That’s bad for humanity, because most of the carbon that doesn’t go into the ocean ends up back in the atmosphere.

Not all of the carbon in the bodies of the phytoplankton would have sunk deep enough to be locked away from the atmosphere. But even if only a quarter did, once converted to CO₂ that could match annual emissions from the entire aviation industry.

The ocean as a sponge

Many ocean-based CO₂ removal technologies will alter the composition and abundance of phytoplankton.

Biological ocean-based CO₂ removal technologies such as “ocean iron fertilisation” seek to increase phytoplankton growth. It’s a bit like spreading fertiliser in your garden, but on a much bigger scale – with a fleet of ships seeding iron across the ocean.

The goal is to remove CO₂ from the atmosphere and pump it into the deep ocean. However, because some phytoplankton crave iron more than others, feeding them iron could change the composition of the population.

Alternatively, non-biological ocean-based CO₂ removal technologies such as “ocean alkalinity enhancement” shift the chemical balance, allowing more CO₂ to dissolve in the water before it reaches chemical equilibrium. However, the most accessible sources of alkalinity are minerals including nutrients that encourage the growth of certain phytoplankton over others.

If these changes to phytoplankton favour different types of zooplankton with different sized appetites, they are likely to change the strength of the biological pump. This could compromise – or complement – the efficiency of ocean-based CO₂ removal technologies.

Moving forward from a sea of uncertainty

Emerging private-sector CO₂ removal companies will require accreditation from reliable carbon offset registries. This means they must demonstrate their technology can:

- remove carbon for hundreds of years (permanence)

- avoid major environmental impacts (safety)

- be amenable to accurate monitoring (verification).

Cast against a sea of uncertainty, the time is now for oceanographers to establish the necessary standards.

Our research shows CO₂ removal technologies that change phytoplankton communities could also drive changes in carbon storage, by modifying zooplankton appetites. We need to better understand this before we can accurately predict how well these technologies will work and how we must monitor them.

This will require tremendous effort to overcome the challenges of observing, modelling and predicting zooplankton dynamics. But the payoff is huge. A more reliable regulatory framework could pave the way for a trillion dollar, morally imperative, emerging CO₂ removal industry.

Tyler Rohr receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the ICONIC Impact Ocean Co-Lab, which is managed by the National Philanthropic Trust. Tyler Rohr has previously consulted for carbon offset registry Isometric.

Ali Mashayek advises Puro Earth, a crediting platform for carbon removal, on feasibility and environmental impacts of the carbon removal methodologies. He receives research funding from UK Research and Innovation and US Office of Naval Research.

Sophie Meyjes receives funding from the Natural Environment Research Council through the C-CLEAR Doctoral Training Partnership.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.png?w=600)