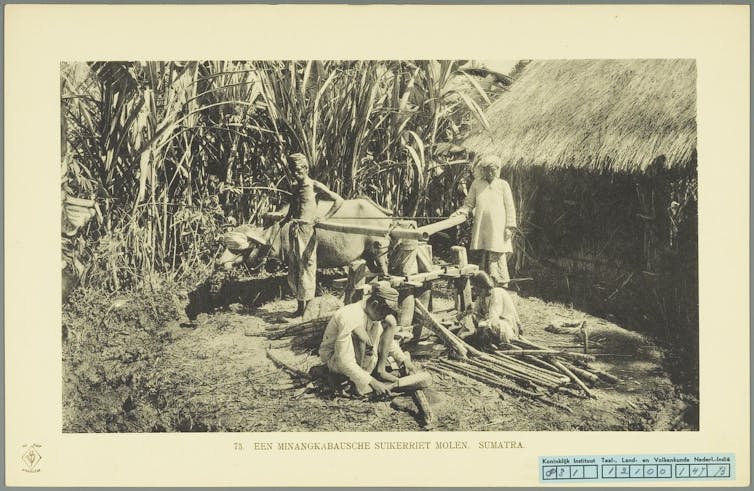

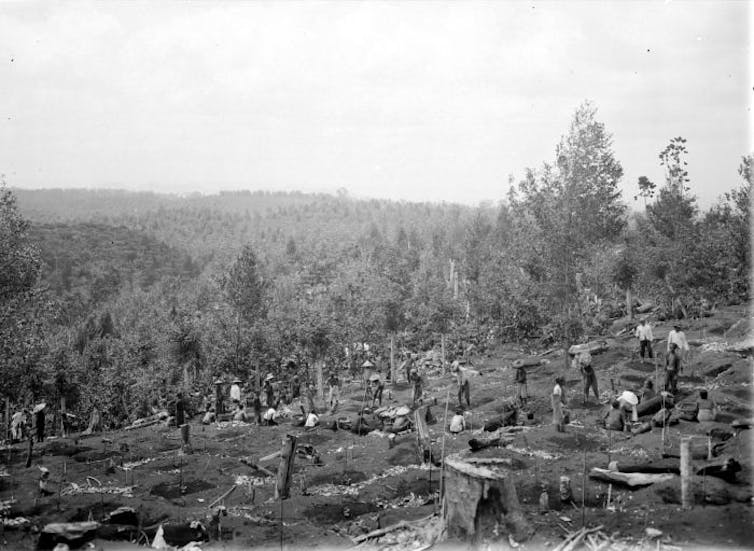

In the early 20th century, the region now known as Indonesia – then the Dutch East Indies – was Europe’s largest colony after India. It was a major producer of tropical commodities, like rubber and sugar, which were drivers of the global economy.

I study the consequences of international trade during the colonial era on income distribution and well-being in developing countries. My research, examining varying levels of inequality in different Dutch East Indies regions during the early 20th century, shows how the global plantation and trade systems – in the context of colonial institutions – affected the livelihood of the people in colonised countries.

Studying inequality in the Dutch East Indies gives an idea of how economic development is negatively affected by high levels of inequality when economic freedom is lacking, such as under colonialism.

Inequality levels in the colonial era

Earlier research on Dutch East Indies underlines how the population boom in Java in the late 19th century led to increasing inequality and “shared poverty”.

Others pointed out high inequality levels between ethnic groups (Indonesians, Chinese and European) and how the top 1% of the population pocketed between a 12% to 20% share of the colony’s overall income in the 1920s and 30s. Some also hinted that smallholders’ exposure to fluctuating commodity prices and the increasing land rent resulting from booming cash crops boosted inequalities.

My research focuses on the residency level comparable to present-day provinces. (Residencies, or Karesidenan, were a regional government level below that of a colony.)

I looked at data on income tax in the 1920s, land distribution, and wage levels in various residencies. I combined these data with colonial reports on indigenous welfare published during the same period.

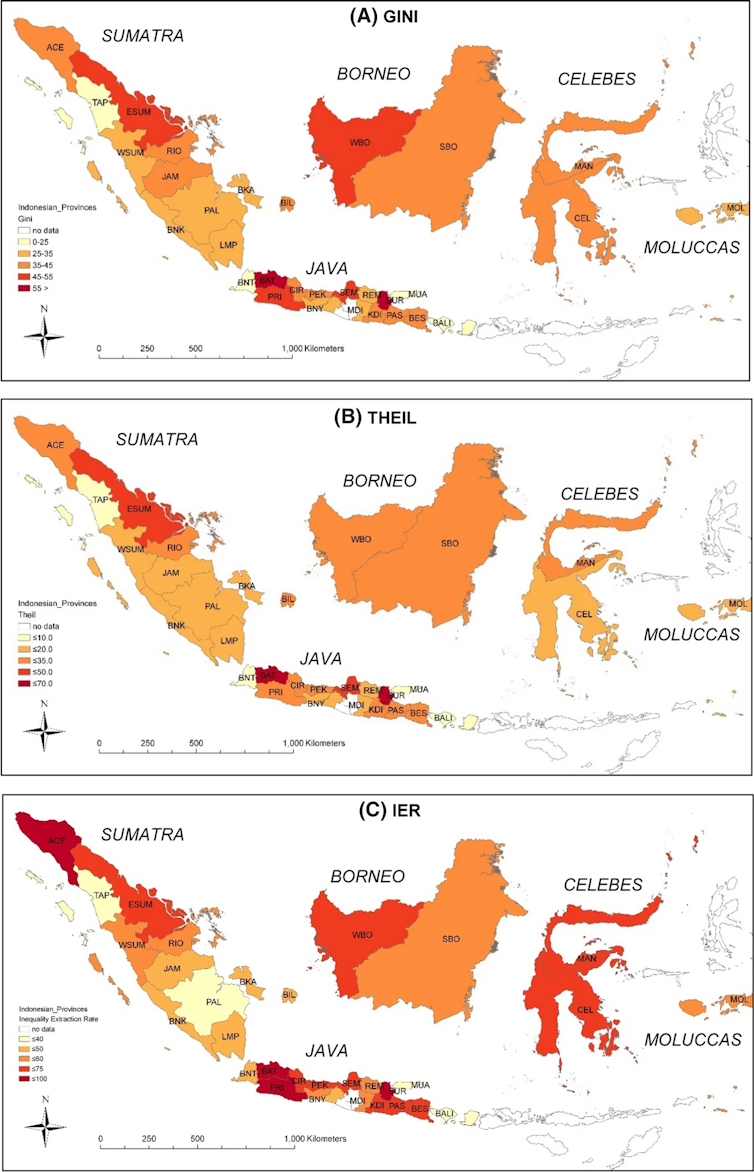

To analyse the data, I used four inequality benchmarks. They are the Gini coefficient, the Theil index, inequality extraction ratio (IER), and top income ratio (TIR).

The analysis found that Batavia (now Jakarta), Surabaya, Priangan (now West Java), Semarang, East Sumatra (now part of North Sumatra) and West Kalimantan had the highest levels of inequality.

Batavia, Surabaya and Semarang had a high European presence. The wealthiest people from the three dominant ethnic groups resided there. Meanwhile, forced coffee planting in Priangan was the root cause of the high disparity in that region. As for East Sumatra, inequality in this region was set against the backdrop of the dominance of plantation crops and the low income of unskilled labourers.

Low inequality levels were found in West Sumatra, Jambi and Rembang. Meanwhile, Banten, Madura, Bali and Tapanuli had the lowest levels of inequality.

Residencies where smallholders – instead of large European plantations – drove export expansions (like in Jambi and West Sumatra) had low inequality levels. This underlines how the dynamics of indigenous people in export-based economies are critical. It also shows that areas focusing on food crops rather than cash crops have a more equal income distribution.

Bengkulu, Tapanuli and Bali – for example – had little in the way of exports.

However, low inequality levels may also be correlated with low average income levels due to infertile lands, hindering the economy from expanding.

This was the case in Banten and Madura. The story from the novel Max Havelaar by Multatuli, which tells how a Banten local official confiscates peasants’ buffaloes because there is nothing else to extract, may illustrate this situation.

Lastly, top income ratios were relatively low in Sulawesi, Tapanuli and Jambi – areas with little European economic activities.

How globalisation affects inequality in colonised countries

Earlier studies show that inequality in Indonesia rose when globalisation spread during the peaceful decades leading up to World War I.

I looked at per capita export value data to assess the Dutch East Indies’ interaction with the global market. I also examined the sizes of plantation estate areas compared with residency areas. This is considering that export commodity production using the estate system may cause inequality compared to production by smallholders.

Europeans started to own private plantations when the colonial government introduced the agriculture law in 1870. Before that, the Dutch government had a monopoly over export plant cultivation.

The law underlined that irrigated rice fields belonged to the people.

However, the colonial government claimed ownership over the remaining vacant lands. They could be leased for 75 years to Europeans to develop commercial crop plantations - while being mindful of customary laws and local elite ownership to avoid any potential uprising.

By measuring the inequality index and comparing it with the estate area, my research found that the larger the estate area, the higher the inequality level was. This is not surprising considering that export agriculture was among the primary sources of surplus income in the late Dutch East Indies era.

Most of this income went to estate owners and management, while plantation labours only received a tiny fraction of it in low wages. A great portion of estate incomes was transferred to the Netherlands.

I looked at 12 sample residencies with high coverage of income tax collection to see how changes in exports and estate sizes affect inequality.

These areas were Bangka, Bengkulu, Belitung, Jambi, Lampung, Maluku, Palembang, Riau, Southeast Kalimantan, East Sumatra, West Sumatra, and Tapanuli. The analysis shows that every increase of 1% area size proportionate to the residency area saw a spike in the inequality indexes (3.7 in Gini and 4.2 in Theil).

In short, global trade affected inequality when agricultural exports were organised via estate production. The relationship between plantations and inequality suggests the importance of the institutional context in which global trade is taking place.

What can we learn from this research?

We can see that inequality levels radically differed between different areas in the archipelago.

Poor regions with no exports, such as Banten and Madura, had lower inequality levels in the 1920s. On the other hand, inequalities were present in relatively wealthier residencies like West Sumatra and Jambi.

As for areas with high income and commercial activities run by the Europeans, like Batavia, Surabaya and Semarang, their inequality levels were exceptionally high, with Gini ratios above 50 (out of 100).

These data show that even in a single colony, inequality levels may vary and that a single measurement variable would not be sufficient to understand the disparities in place. It is also crucial to go deep into regional government institutions and not merely take a birds-eye view at the country level to understand the inequality trend and the factors behind it.

Therefore, when taken into the global context, the essential factor influencing inequality is not the increasing levels of cross-border trade, but how these trade activities are organised. In the colonial context, this is clear when comparing whether large plantations or smallholders are predominantly engaged in export production.

Pim de Zwart does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.