Central North Island councils hated the idea of a Te Tiriti-founded co-governance model when it was mooted for the Waikato River. They saw a power-grab by Māori – even an asset grab. In practice, it wasn’t that at all

Seats at the Table series: Co-governance is nothing like you think | Tūpuna Maunga Authority | Newton Central School - Te Kura a Rito o Newton | Kotahitanga mō te Taiao Alliance | Waikato River Authority

In 2008, Waikato-Tainui and the government signed a deed to settle the tribe's claim to the Waikato River. Two years later, with $220 million vested in a body tasked with restoring the health and wellbeing of the river, a joint governance and management structure was formed.

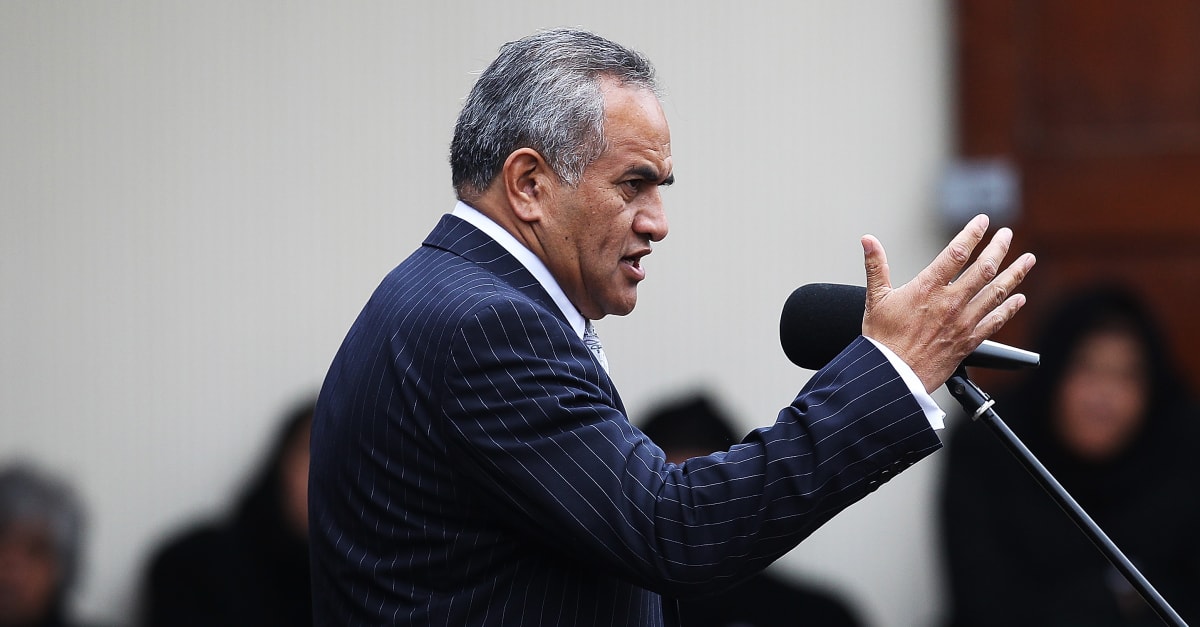

The five river iwi had fought hard for co-governance – Māori leaders and Crown representatives having an equal say in decision-making about the river, says Waikato-Tainui leader and former MP Tukoroirangi Morgan. For iwi it was non-negotiable.

And for the councils? They absolutely hated it.

READ MORE: * Co-governance – it's nothing like you think * Reframing co-governance: Jackson's warning to Labour * 'It sends shivers down my spine what we manage to achieve'

Morgan was a key negotiator in the settlement process, and founding co-chair of the Waikato River Authority, alongside former National MP John Luxton.

“Councils hated the idea of sharing power,” says Morgan. “I remember going into the meeting the night before we signed the deed of settlement and you could slice a knife through the air. I had five mayors sitting in the room – all of them hated the idea of sharing power with Māori.

“And I said to them, ‘The winds of change are blowing. You can’t turn this back. This is a treaty settlement. But the iwi cannot live on an island, we have to work with all aspects of the community – corporate, council and community members. We have to do this together.'”

Bob Penter was the senior Crown-appointed adviser to the Waikato River Guardians Establishment Committee (GEC) and played a pivotal role in the treaty settlement and setting up Waikato River Authority. Now he’s its chief executive.

“The concern [from councils] was we had this co-governance entity which was partly iwi-governed and seemed to have these unheard of powers, and this unheard of status, for this new vision and strategy document," says Penter. "The regional council at that time was particularly concerned its role was going to be overridden by this new entity which also seemed to have responsibilities in relation to waterway health and wellbeing.”

There are uncanny parallels with the fight many councils are putting up against the Government’s proposals to use the 50:50 council:mana whenua, consensus decision-making co-governance model at the top of the four new post-reform Three Waters entities.

An alternative proposal, commissioned by anti-Three Waters councils, got rid of the co-governance aspect, giving more power to the territorial authorities and downgrading Māori input into decision-making at the community level.

South Wairarapa district councillor Alistair Plimmer spoke for many of his colleagues around the country when he said co-governance was the "single biggest stumbling block" in the Three Waters legislation and the point that caused the most contention.

Meanwhile, “co-governance means Bro-governance”, New Zealand First leader Winston Peters said in a speech opposing (among other things) Three Waters.

Co-governance was inconsistent with democracy, Peters said, echoing the argument that power should be in the hands only of elected representatives, and that Māori having being given 50 percent decision-making authority in an organisation was incompatible with their numbers in the population.

Tuku Morgan, now the newly appointed chair of the iwi representative group for ‘entity A’, the largest water body under the Three Waters reform, doesn’t buy the anti-democratic argument.

“Democracy, in very simple terms, for Māori, is the tyranny of the majority. The net effect of that is Māori will always be on the side, we will not be participants.

“For the purposes of our treaty settlement we were very clear to the government we needed an equitable say – 50:50 down the middle. And to his credit [then Treaty Negotiations Minister] Sir Michael Cullen saw the sense in that much more equitable situation.”

For Morgan, co-governance of the Waikato River Authority was inevitable, because of the importance of the river to Māori and because of the land confiscation when colonial troops drove Waikato iwi from their land in 1864.

“We lost 1.2 million acres, including the most precious taonga – our water,” he says.

“And from that time, we have never been included in anything to do with our ancestral river ... Iwi watched helplessly as council after council degraded our river over many, many years – and we had no say at all.”

“There is nothing about power here. This is about collective decision making and doing what was best for the river, not for our respective selfish motivations.” – Tukoroirangi Morgan, inaugural co-chair, Waikato River Authority

The talk about a Māori power grab makes Morgan furious.

“These are the very councils that run up huge debts, who can’t control their operations and their spending. And then they talk to us about a power grab.

“Co-governance was always about shared decision-making. Equal numbers of iwi, equal numbers of Crown representatives at the table. No voting – it’s all down to consensus decision-making

“Unlike those councils that scrap and disagree and have extreme views, here we have two co-chairs, both from different worlds, marshalling our two sides.

“Never in the eight years I was the chair and the Honorable John Luxton was the chair, did we ever have to go to a vote. Where there were differences we talked and talked until we came to a consensus decision.

“There is nothing about power here. This is about collective decision making and doing what was best for the river, not for our respective selfish motivations.”

And the furore about co-governance and Three Waters?

It's all about politics, Morgan says.

"This is a straight-out political attack on a government which has had the courage to take something successful, and put it in a situation where it'll bear fruit, where the outcome will be positive for everyone."

Co-governance is "the best form of protection against privatisation of the water assets because Māori will never sell, and retaining ownership collectively is the best outcome for us all", Morgan said in an opinion piece last year. "It is embedded in our DNA through brutally hard lessons, that it is imperative to hold on to taonga, to assets, to ensure they are gifts that can be handed on to the next generation.

In the meantime, co-governance has become the norm at the Waikato River Authority – just how it's done. And once the councils actually saw how it worked, they came on board, Penter says, despite it being a tough sell at first.

“The regional council at that time was lobbying ministers to unwind some aspects of the river authority. They were concerned we were eating their lunch in the waterway space. Our first phase was about winning hearts and minds, about showing people we were there for the right reasons in terms of restoring the health and wellbeing of the Waikato River catchment.”

Within 12 months the authority and the regional council had a partnership agreement, Penter says, and the relationship now is “exemplary”.

“I couldn’t imagine a better partner to work alongside.”

And the health of the river? Not great – yet. The second five-year report card, released in 2021, shows improvements in some areas, but an overall decline, despite $30m spent on almost 200 projects. The river had been degraded over decades and restoring it was going to need an 80-year timeframe, then co-chair Paula Southgate said at the time.

‘Good governance – at the next level’

Penter classifies co-governance as “good governance – but at the next level”.

“Unlike at more traditional board tables, where key decisions can be made by simple majority voting (including when a chair must use their casting vote), a co-governance approach works harder to find consensus, which invariably results in better decisions,” he says.

“Co-governance demands the absolute best practice across the four governance pillars: leading an entity’s purpose and strategic direction, effective governance culture, holding management to account through informed, astute, effective and independent oversight, and effective compliance (eg health and safety through to financial management).

“The governance bar is not lower for co-governance arrangements, it is higher; decision-making is based on good faith engagement. The outcome is that a broad range of viewpoints are heard and measured across the board table, with decisions based on the merits of the discussion and values of the organisation.”

Seats at the Table series: Co-governance is nothing like you think | Tūpuna Maunga Authority | Newton Central School - Te Kura a Rito o Newton | Kotahitanga mō te Taiao Alliance | Waikato River Authority