Creating protected time for teachers to collaborate with colleagues provides – in theory – an opportunity for teachers to improve teaching, and reduces the time they have to spend in the evenings and on weekends preparing for class.

Teachers now report spending an average of four hours a week collaborating with colleagues.

But the unfortunate reality is many Australian teachers find collaborative planning a frustrating waste of time.

That’s a disturbing finding from two recent Grattan Institute surveys of more than 7,000 Australian principals and teachers on teacher workload and curriculum planning.

Read more: Treasurer Chalmers has a $70 billion a year budget hole: we've found 13 ways to fill it

What teachers told us

In Grattan’s 2021 survey on teacher workload, nearly half of teachers (49%) said collaborative planning meetings at their school were a barrier to having enough time for effective classroom preparation.

These findings were replicated across the country, and were apparent in both government and non-government schools.

And while nine in ten teachers in Grattan’s 2022 survey wanted access to curriculum materials they could share with their colleagues, a majority had significant concerns about the extent to which collaborative planning time is used effectively to support this goal.

Teachers told us that time for collaborative planning is often derailed by other issues.

Fifty-five percent said they usually or always end up discussing non-instructional matters during collaborative planning meetings.

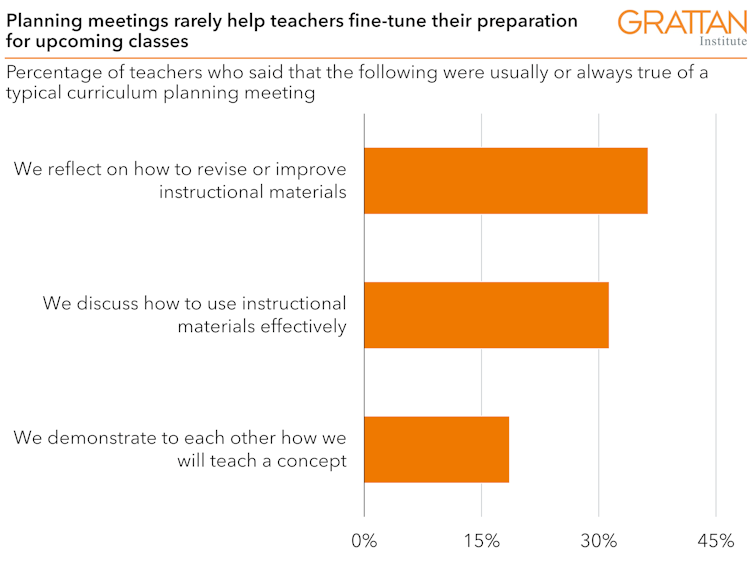

Only about a third said that in these meetings they “usually” or “always” consider how to revise or improve instructional materials, or discuss how to use instructional materials effectively in the classroom.

One secondary school teacher said:

For the dedicated and hard-working teachers, collaborative planning time simply increases their workload […] The ‘spin’ around the benefits of collaborative planning all too often does not reflect the experience.

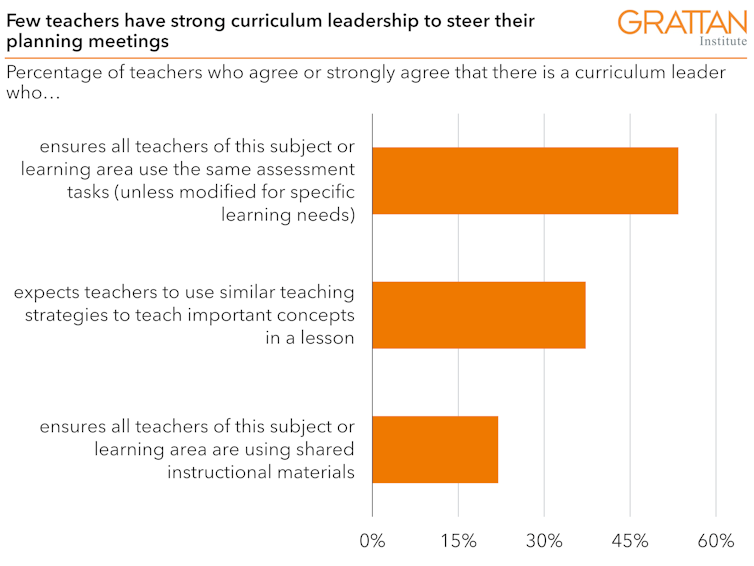

Three-quarters of the teachers we surveyed identified a lack of effective leadership as a barrier to establishing shared curriculum materials at their school.

One teacher told us their collaborative planning meetings were unproductive because there was “nobody moderating different perspectives to ensure a middle ground is reached”.

Another said, “everyone has their own thoughts and there’s little vision to guide everyone in the same direction”.

How to improve things

Grattan Institute’s research on curriculum planning in schools points to two concrete strategies to increase the value of collaborative planning time.

First, use this time to select, establish or refine shared curriculum materials as part of a whole-school approach to teaching and learning.

This is good for student learning: well-planned curriculum materials improve opportunities for students to create deeper knowledge and stronger skills across year levels and subjects.

The Grattan Institute’s research suggests shared school-wide curriculum materials are also associated with increased professional agreement between teachers about what to teach and how to teach it.

Once established, shared curriculum materials can provide a stronger “common language” for teachers to engage in effective forms of professional development and deliver higher levels of teacher satisfaction with planning processes in their school.

Second, strengthen the leadership capacity and curriculum expertise of middle leaders, so that collaborative planning meetings are led more effectively. Without effective leadership, collaborative planning meetings often flounder.

Putting collaborative planning time to work

Grattan Institute’s latest Guide for Principals profiles five schools across Australia which are making the most of this precious time.

At one of the case study schools, Ballarat Clarendon College in regional Victoria, teachers have worked together to develop shared, high-quality curriculum materials across all subjects and year levels.

With this strong foundation in place, teaching teams collaborate in regular “phase two” meetings, which are set up to identify and share great teaching practices.

In the maths department, for example, teaching teams come together roughly once a fortnight to examine student results from recent assessments. If one teacher’s class has excelled, the teacher demonstrates to the group how they taught that specific point to help identify whether a particular approach – such as how they unpacked a worked example – contributed to better learning.

As the teaching teams identify effective strategies, the strategies are noted in the curriculum materials for the benefit of future teachers and students.

These are often small instructional details, such as the best questions for teachers to ask students, the specific words used to describe a process, or common student misconceptions to address.

As one teacher explained

The point is to get the best teaching practice possible. When someone explains in a phase two meeting what they did, we put it in the slides for next year.

The lesson is clear.

Simply setting aside time for collaboration doesn’t always lead to better outcomes for teachers or students.

Effective collaboration requires skilful leadership and a common language.

A whole-school commitment to shared curriculum materials can bring these elements together and create a strong foundation for teachers to work collaboratively on what matters most: great teaching in the classroom that sets students up for learning success.

Jordana Hunter is the Director of the Education Program at the Grattan Institute. The Grattan Institute has been supported in its work by government, corporates, and philanthropic gifts. A full list of supporting organisations is published at www.grattan.edu.au.

Nick is an Associate at the Grattan Institute and is currently training to be a teacher at the Melbourne University's Graduate School of Education.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.