On the one-year anniversary of Jan. 6, conservatives held more than two dozen "Justice for J6" vigils across the country, arguing that most of those arrested for storming the U.S. Capitol "were political neophytes" who hadn't realized what they were doing was wrong. In February, the Republican Party described the insurrection as "legitimate political discourse" in censuring the two GOP members of Congress who joined the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 events. And in early April, Donald Trump told the Washington Post that he had wanted to march to the Capitol himself, saying, "I would have gone there in a minute" if the Secret Service hadn't prevented it.

All this is part of a growing effort to normalize the riot at the Capitol, and to cast its perpetrators as overwhelmingly "ordinary people" who got caught up in the momentum of something beyond their control. But last week came decisive evidence that this simply isn't true: At least a third of those arrested in conjunction with Jan. 6 belong to a far-right network that is not just deeply interconnected but resilient and adaptable.

RELATED: How Christian nationalism drove the insurrection: A religious history of Jan. 6

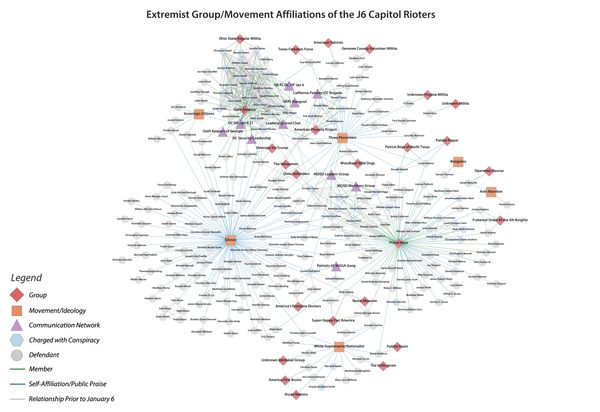

Last Thursday, Michael Jensen, a senior researcher at the University of Maryland's National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START center), released preliminary findings on the ideological motivations and connections of about 30 percent of all Jan. 6 defendants. While his research is ongoing, Jensen has already found that at least 244 of the 816 people arrested to date were either members of "extremist" organizations or self-identified with them. In his widely-shared map of the network (embedded below), Jensen documented at least 700 relationships between the defendants and both well-known far-right groups as well as more diffuse movements, including white nationalists, anti-vaccination activists, militias, militant anti-abortion groups, QAnon adherents and more.

While the "ordinary people" narrative around Jan. 6 has become ubiquitous, Jensen says, "These aren't ordinary relationships — or, at least, they shouldn't be."

Jensen spoke with Salon last Friday.

How did you come to research the Jan. 6 defendants as a group?

The START center's mission has always been to advance the scientific study of the causes of terrorism and how best to respond to it. We've primarily done that through developing datasets around terrorist behaviors, terrorists themselves, the types of weapons and tactics they use and so on.

Within the START center I run the team that looks at extremism in the United States. When we started working on that topic in 2013, one of the key buzzwords was this concept of radicalization: Everybody wanted to know how and why somebody could adopt these beliefs and then mobilize on behalf of them to the point where they're committing crimes and killing people.

We had a lot of great theories, but essentially no data to test them. So our proposal was to start collecting data on individuals that had radicalized to the point of committing crimes and figure out everything that might have mattered in their radicalization process: family dynamics, schooling and work experiences, social groups, how they were introduced to extremism and other risk factors like mental health or substance use concerns. We also wanted to make sure it was cross-ideological, because extremism in the U.S. is quite diverse.

In 2016, we released that dataset, "Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States," for the first time. It has information on over 2,200 individuals radicalized in the U.S. to the point of committing crimes — everybody from white supremacists and anti-government militia members to QAnon followers, eco-terrorists and ISIS-inspired individuals. We map all of them, with the ultimate goal of figuring out what to do about it.

We certainly noticed an uptick in cases during the Trump presidency, especially associated with the extreme right. We were already tracking these cases for our database. Then Jan. 6 happened and was obviously a watershed moment. In a busy year, we might identify 300 individuals that qualify for inclusion in the database. Here we had one day where potentially hundreds, if not thousands, might qualify — people clearly motivated by political goals, by extremist ideology.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

We knew it was going to take time for enough information to be available about the defendants to know who really qualifies for inclusion. But in the early days after Jan. 6, this narrative was forming that, "These are not extremists. These are ordinary people that got caught up in the moment." I was skeptical because, having done this for almost 10 years, I knew the data just wasn't available yet to have confidence in those claims. It takes a while to learn about the perpetrators of these crimes when there's only one of them, let alone a couple thousand.

What determines who gets included in the database?

The most important criterion is a clear link between criminal behavior and the ideology the individual espouses. We run across plenty of cases of individuals linked to white supremacy, for example, who commit a drug crime that has nothing to do with their ideology. That's not somebody we would include. With Jan. 6, there's a clear link between the criminal act and the beliefs.

As a team, with Jan. 6, we are still very much discussing whether everybody just qualifies for inclusion because this was clearly an event motivated by a political goal, or do we limit it to just those with an extremist group affiliation?

What role does the "ordinary people" narrative play?

It does a couple of things. It downplays the reality of the event itself. There have been Republican members of Congress who claim this was basically a Capitol tour that got out of hand and these are law-abiding people who made a mistake — or, in some representatives' view, they didn't make a mistake at all. So politicians latch onto this narrative to dismiss Jan. 6 as a significant event.

Almost across the board, defense lawyers use this narrative to pass off their defendants' actions as just getting caught up in the moment: They had no intention of going to the Capitol and doing something harmful, they just lost control. That's just not true of a lot of the defendants. There's clear indication that they came prepared to engage in violence and had coordinated it to some extent ahead of time. We're losing sight of just how coordinated and orchestrated it actually was when we pass it off as ordinary people that got caught up in the moment.

If we say Jan. 6 is something "ordinary people" do, we're saying it's mainstream to get upset about fake election fraud and riot at the Capitol.

The other thing the narrative does is potentially make the problem of mainstreaming extremism worse. The fact that so many people arrived at the Capitol that day was because extremist views, disinformation and conspiracy theories had made it into the public discourse around everything — not just politics, but also public health, education, immigration, all the things that matter. When we say the Capitol riot is something ordinary people do, it's like it's a mainstream thing to get upset about fake election fraud and riot at the Capitol. That's why the narrative is potentially damaging to our ultimate goal of making sure this never happens again.

What was the starting premise of your research, and what did you find instead?

I went in expecting that I'd find the cases everyone knows about — the high-profile Oath Keepers and Proud Boys that have been all over the news, the QAnon Shaman — and I wouldn't find many others. I started digging through court records, social media posts and everything else I could get my hands on, and found there were a lot of people that had some connection to these movements. There were both card-carrying members of these organizations and even more that had self-identified as part of these movements, so while they may not be dues-paying members of the Proud Boys, they were at demonstrations ahead of Jan. 6 alongside the Proud Boys and putting it on their social media accounts and promoting the views of the group.

I wanted to know how many of these people were connected prior to Jan. 6. Within groups like the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers, there were a lot of connections established prior to that date: the individuals at rallies together or doing military-style training together. What I thought was going to be a very easy exercise in finding a handful of connections quickly turned into many, many hours of poring through thousands of pages of court documents and social media posts and news articles finding these relationships.

I'm under no belief that I found them all. If we had perfect access to all the information, that 30 percent number I reported would be higher.

What were some of the most concerning connections that you found?

There are the individuals people know about who are fairly influential in modern U.S. extremist movements: [Oath Keepers founder] Stewart Rhodes, [Proud Boys chairman] Enrique Tarrio, the leaders of these big organizations that have a relationship to each other that allows for information, people and tactics to flow easily between them. But there are lesser-known characters who play a really important role as well.

Alan Hostetter perfectly encapsulates Jan. 6: He's a Three Percenter, he's anti-vax, he's anti-science. He's spoken at QAnon rallies, and now he's using sovereign-citizen tactics.

For example, Alan Hostetter, I think, perfectly encapsulates Jan. 6. He's a Three Percenter. He's anti-vax, he's anti-science. He has spoken at QAnon rallies. He has links to the QAnon Shaman. Now, in court, he's using sovereign-citizen tactics. He developed his own anti-government militia called the American Phoenix Project and mobilized his fellow group members to the Capitol on that day. So he's sitting at this intersection of just about every ideology that was present at the Capitol.

Somebody like that is important because they transmit ideas from one movement to another. When he speaks at a QAnon rally, he brings sovereign citizen and anti-government views to a movement that maybe otherwise isn't hearing those views. He's able to make connections between those disparate ideologies and bring them closer together.

That seems to mirror the growing enmeshment of different right-wing movements, to the point that we're seeing an almost seamless overlap between anti-vaccination sentiments, election lie narratives, QAnon conspiracy theories and so on.

QAnon played a pivotal role in bringing together groups that weren't necessarily in opposition but had different goals and ideas. QAnon is a self-interested conspiracy theory. It doesn't care about coherence or whether the predictions come true. It wants to survive. It wants to grow. So it's opportunistic and will bring anybody into the fold.

QAnon folks, at the beginning, had a strong connection to the sovereign citizen movement. But you've seen influential people within the movement become more overtly antisemitic, and that brings in the white nationalists. You see them being more overtly anti-government and pushing election conspiracy theories, and that brings in the militias. Then you see them being anti-vax and anti-lockdown, and that appeals to folks that aren't connected to the broader anti-government movement but are vulnerable to radicalization. So QAnon becomes this connective tissue, drawing these individuals closer together and putting them under this umbrella conspiracy theory.

Of course, that was all fueled by the online ecosystem they can exploit to make these connections. Now it's found a home on places like Telegram, where the Oath Keepers, Proud Boys and neo-Nazi groups also found a home. When you go on Telegram now, it's very common to find channels with lots of members that mix all these things. It's a QAnon channel, but also a white supremacy channel that has anti-government militia stuff going on too. What you now see is an almost complete overlap between what were once different sub-ideologies within the far right.

Some groups that track far-right movements take issue with the terminology of "extremism," arguing that casting far-right ideologies as extremism can obscure their connections to systemic power and how widespread they really are.

I understand that idea: When you label something "extremism," it's supposed to mean that you're labeling it as rare. And what we've seen over the last five years or so is that there's an awful lot of it now. I think you're absolutely correct that you run the risk, when you label something as extremism, of people passing it off as an exception, not the rule.

But the problem with not labeling it extremism is that you normalize it. We need to remind people that it is extreme to believe these things. It's extreme not to trust science, not to believe evidence, to promote the overthrow of democracy. They are unfortunately now common views, but they are extreme as well, and our goal should be to make them uncommon again.

Will you be mapping other ideologies or groups as you go forward, such as the Christian nationalist movements that were so prevalent on Jan. 6?

As we learn more about both those broader movements and specific smaller organizations, we'll keep adding them. My ultimate goal is to map Jan. 6 within the larger extremist context, to show it as one event among many that bridge not only the main groups that were present at the Capitol that day, but others [that weren't].

The idea is to get a better view of the broader extremist ecosystem over the last several years so we have a more complete picture of what we're dealing with. There's a volume challenge — this was a spare-time project — but that is the ultimate goal because Jan. 6 wasn't an isolated event. It happened within a growing context that remains to this day.

We would look at fairly extreme religious organizations or organizations that are promoting anti-abortion views or are linked with QAnon, things like that. I don't have any plans at this point to figure out the religious affiliation of every single defendant, but to the extent that specific evangelical groups present at that Capitol that day have linked themselves to this broader extremist movement, then absolutely I would include them.

What do these findings tell us about the shape of the right today?

It teaches us what I think we knew, but didn't have the evidence to completely support, which is that this is a big, well-connected movement and defeating it is going to be difficult. It can't just be a strategy of targeting one organization or individual. This is like a virus: It will adapt and evolve to stay alive and keep infecting individuals.

This is a big, well-connected movement and defeating it will be difficult. It's not about targeting one organization or individual. This is like a virus: It will adapt and evolve to stay alive and keep infecting people.

The leadership of two big organizations, the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys, are being decimated right now. And it probably won't matter that much. Those organizations will survive because they already decentralized and made inroads with all these other movements, so they have people in place to keep the ideology moving forward even if Stewart Rhodes ends up in jail for the next 20 years, or we don't hear from Tarrio again for decades.

Defeating it also can't just be a law enforcement strategy. We're not going to arrest our way out of this problem. This is a public education problem as much as a criminal problem. We need to be better at dispelling disinformation and educating our kids about how to think critically about conspiracy theories and to see the manipulation in them. We often talk about adopting a public health model, where prevention plays as big a role as intervention and interdiction.

Unfortunately, we just don't, at a national level, have the mechanisms in place to do anything like that. We see local programs that can have great outcomes. But scaling that up to reach everyone is a massive challenge that requires resources we don't have. But it's ultimately what is needed.

The other point is just how mainstream these beliefs have become and how quickly something on the fringe makes its way into the mainstream. The direct connections now between things like QAnon and politicians allows these ideas to move rapidly from a Telegram channel into mainstream political discourse. We're seeing it all over the place — with Supreme Court confirmations, and now these ridiculous protests around Disney. That stuff finds its way into the mainstream instantaneously because of the direct connections those ideas have to influential people. The mainstreaming of these beliefs is here, and I don't know how we reverse course at this point.

How do you grapple with ideas like this becoming a mass movement? Is it even possible in our current political setup?

You could take the view that the ship has sailed. I don't know that we're going to turn it around completely at this point because of the political utility it has. Adopting a hardline view is politically a winning strategy for individuals that have the ear of the masses. Part of it is going to take convincing them that the political gains they achieve from moving far to the right are not worth it because of the ills that it causes to the greater body politic. I don't know how you make that a convincing argument to those that have adopted that strategy.

The fact that you've got some 100 individuals linked to QAnon running for public office in the midterm elections is just astounding. And what's going to be even more astounding is that some of them are going to win. So that cohort in Congress is going to grow.

We could stop voting these people in. That would do a lot to send a signal that it's not a winning political strategy. But unfortunately, that's just not what mobilizes people. People are mobilized by polarization, by radicalization. Maybe that's just basic human nature. Until we solve that problem, I think it remains a winning strategy and we're going to be dealing with this for some time.

Read more on Jan. 6 and its long-term ripple effects: