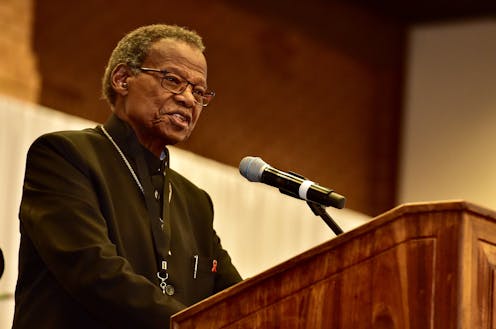

Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi, who has died, was a history maker. He was born on 27 August 1928 into a tumultuous global century, and into the local conditions of racist rule.

A man of singular political talent, Buthelezi was among the country’s most influential black leaders for the majority of his long and remarkable life. Yet he occupied an anomalous position within the politics of the anti-apartheid struggle. He brokered Zulu ethnic nationalism, feeding a measure of credibility into apartheid ideals of “separate development”. This, against growing calls for unity under a democratic, South Africanist banner. But he claimed his position to be a realistic strategy, as opposed to armed struggle.

He will be remembered as the founder and stalwart campaigner of the Inkatha Zulu movement. He’ll also be remembered for the violent civil strife between his followers and the United Democratic Front and African National Congress (ANC). The violence claimed nearly 20,000 lives during the last decade of racist National Party rule.

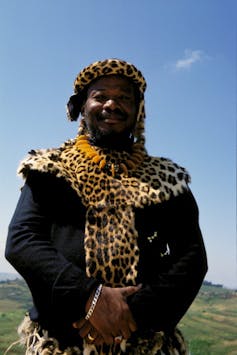

Buthelezi’s mother was Princess Magogo, granddaughter of King Cetshwayo and sister of King Solomon. She was an important person in her own right. His great-grandfather was said to be “prime minister of the Zulu nation during King Cetshwayo’s reign”. He took up this role himself in relation to the monarchy of King Goodwill Zwelithini.

A complex figure, Buthelezi (or Shenge, as he was known to many) enjoyed traditional titles of chief and prince. He was also rooted in Christian and modernist ideals.

Buthelezi lived his personal life as a dedicated Anglican, with a close connection to Alpheus Zulu, Bishop of Zululand. He enjoyed a long marriage to Irene, who died aged 89 in 2019. He tragically endured the deaths of five children, two of them of AIDS, a fact he declared publicly. He was taking a brave stand against stigma at a time when most political elites fostered a climate of denial around the disease.

Political career

His political career began early. He joined the ANC Youth League and was expelled for student political protest while studying at the University of Fort Hare in 1950. Set to become a lawyer, and due to do articles with South African Communist Party lawyer Rowley Arenstein, he changed route to take up politics full time. This was a crucial turning point, which he attributed to Chief Albert Luthuli. Luthuli, a father figure whom Buthelezi claimed as a mentor, bridged Zulu traditions and modern liberal ones in his role as both a chief and as ANC president.

Yet South Africa was changing. When Buthelezi chose to engage with the politics of apartheid’s “homeland” policy from 1970, he initially did so with widespread support. Homelands or “bantustans” were the 10 impoverished rural areas reserved for black people, where, as ethnic entities, they exercised nominal self-rule separate from the developed rest of the country ruled exclusively and in the interests of all white people.

He was occupying a platform from which he also kept the internal flame of political opposition alive. He did this first linked to the name and direction of the banned ANC, which had reconstituted itself in exile. Buthelezi could legitimately claim to have blocked the National Party’s vision of ultimate complete ethnic “homeland” separatism, by refusing “independence” for the KwaZulu territory.

Had he not opposed the apartheid state’s plans for the then fledgling King Goodwill, modelled on the monarchy of Swaziland (now Eswatini) – an executive monarch with total political and economic power – the region’s history would have unfolded very differently. In KwaZulu this would have meant a single person in control (the young Goodwill Zwelithini), beholden to the purse-string holders in Pretoria.

Because of Buthelezi’s stand on “independence”, and in the climate of the Cold War, he was considered by many western leaders the most likely and desirable black leader to bring about a democratic, and capitalist, South Africa.

Buthelezi consistently called for the release of political prisoners. He formed a political movement, Inkatha, in 1975, and ensured its growth and survival – and thus his own – within the KwaZulu base. In 1979, he fell out of grace with the ANC in what he continued to consider both a misinterpretation of his objectives and a manipulative power play, leaving a sore point that endured.

Buthelezi increasingly worked his own base, using media masterfully in a pre-internet world. He distributed every speech on a mailing list, nationally and internationally, drawing in supportive journalists and political analysts. In the 1980s, he drew finances for innovative and convincing research, inaugurating the Buthelezi Commission Report, which investigated the entwined economies of Natal and KwaZulu. This was followed by the KwaZulu-Natal Indaba of 1986, where the potential of a post-apartheid federal system was explored. Coming just before the political manoeuvres in the late 1980s and the transition in the early 1990s, and from such a strong source, it would have confirmed to negotiators on all sides that ethnic “homelands” would continue to feature in a democratic South Africa.

Attempts to initiate national linkages such as the South African Black Alliance failed to take off. Likewise efforts to present himself as a national politician, for example through annual mass meetings in Soweto, the massive black urban settlement outside Johannesburg.

Buthelezi never managed to escape the political damage of “participation” and working “within the apartheid system”. His association with Zulu ethnic authority both served and undermined him. When the ambiguity of his affiliation to the ANC came to a head in 1979, he was increasingly dependent on the apartheid state. He became, inescapably, part of the civil war waged from 1985, sharing the ANC as enemy with his apartheid state supporters.

For its part, the ANC could not accept another internal political position from internal structures not already committed to it. This especially once trade unions grew and civil unrest took on organisational forms under the United Democratic Front, which fully supported the exiled ANC movement.

During the complex negotiations for a democratic country – which he argued made him a bit player – Buthelezi withdrew from participation, against the background of the raging civil war. He returned after the KwaZulu government had passed legislation that ensured the clear continuation of ethnic rule in the region. It also guaranteed that all “homeland” land would continue directly under King Goodwill, as the Ingonyama Trust Land.

Other promises were made to Buthelezi, the non-fulfilment of which rankled him thereafter. While a member of the Government of National Unity (1994-1996), he even served as acting president. He continued to lead what was now the Inkatha Freedom Party for most of his remaining years.

He was centrally involved in the disputatious unfolding of selecting a successor to King Goodwill after his death in 2021. The continuing complexities of Zulu ethnic politics, including the installation of King Misuzulu kaZwelithini in 2022, bedevilled Buthelezi’s political roles into his 90s.

Talent and contradictions

Buthelezi left traces of his life firmly in South Africa’s history over the past momentous 80 years or so. It is therefore not surprising that there will remain very different assessments of his roles and legacies. Some of the titles that were and can be attributed to him would include, at various moments: Zulu chief and prince, bantustan prime minister and ethnic prime minister to the Zulu king, and acting president of a democratic South Africa.

Others are warlord, stooge and collaborator, internationally recognised statesman, ANC stalwart, Zulu, Christian, family man. Just before his death king-maker could be added.

A man of immense talent, and contradictions, Buthelezi anticipated in his politics the variegated allegiances of power and interest that would reveal themselves, with new bids for authority and wealth, into a new era.

Gerhard Maré does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.