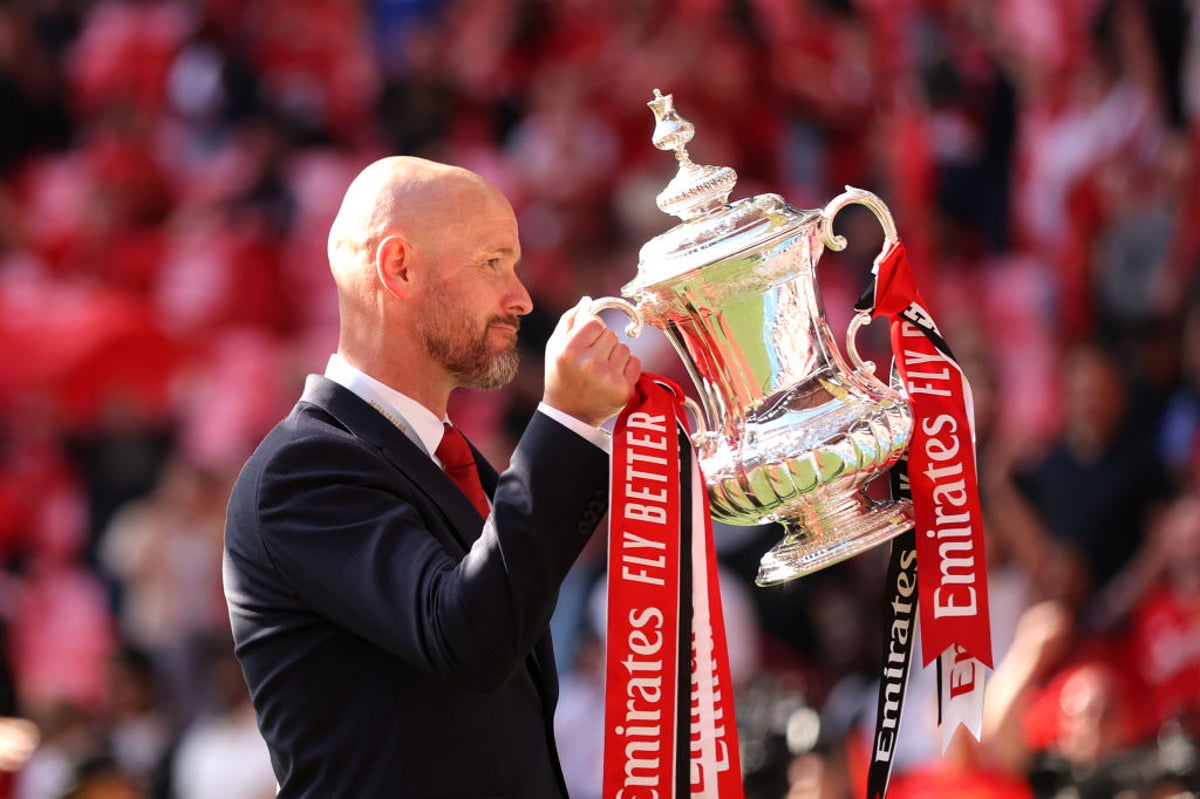

Erik ten Hag was sat in the same seat he had been 15 months earlier when, at the peak of his powers and his popularity, he declared: “I love this club.” Some 15 months later, he struck a defiant tone. “If they don’t want me any more then I go somewhere else to win trophies because that is what I did my whole career,” he said. He was in the depths of Wembley, having added the 2024 FA Cup to the 2023 Carabao Cup. His first piece of silverware came when Manchester United had just beaten Barcelona, when they seemed to be surging into title contention. His second came after the combination of their lowest ever Premier League finish and their poorest ever Champions League campaign.

United decided they did want Ten Hag. Sort of. And eventually, after two-and-a-half weeks in limbo, he was confirmed as their manager for next season; potentially longer, given they are discussing a new contract. And yet if there is a logic to making an end-of-season review under new owners as thorough as possible, if United were eager to avoid knee-jerk reactions, the process has scarcely been a vote of confidence in Ten Hag.

It emerged that Sir Jim Ratcliffe met Thomas Tuchel last week. United have considered the cases of various other potential candidates, too; when Kieran McKenna decided to stay at Ipswich, it may have boosted Ten Hag’s chances of remaining in situ. It is no secret that Gareth Southgate has admirers in the United hierarchy, either. Ten Hag still feels on trial: there was something sensible, too, in United opting not to make a change before the incoming chief executive Omar Berrada and sporting director Dan Ashworth start, but then they will have the chance to monitor Ten Hag more closely.

For now, he is a rare survivor of the old regime at Old Trafford. The winds of change have carried away those who employed Ten Hag, those who flanked him in the higher echelons of the club he joined. He has bucked the trend. His achievement in winning the FA Cup, and the manner of the final, carried some weight. So, too, did the development of Alejandro Garnacho and Kobbie Mainoo, the faces of Ten Hag’s faith in youth. There is hope that, after slow starts, Andre Onana and Rasmus Hojlund can continue to improve last season, the anticipation that 2023’s third big signing, Mason Mount, will deliver more when fit. United accepted Ten Hag’s explanation for last season’s underachievement, feeling the extensive injury list, and loss of players in key positions, was a significant mitigating factor.

If Ten Hag may benefit from the perception that he was hampered by those around him, there could be a corresponding expectation from Ineos that he will excel with their chosen representatives installed. Ten Hag will be reined in by the new brains trust: perhaps he needs to be, given his record in the transfer market, his £400m outlay and infamous fondness for graduates of the Dutch league. It is not only United’s issues with PSR that mean there can be no mistake of the £85m disaster of Antony; with Ten Hag staying, too, it means there will be no immediate return for the £73m Jadon Sancho.

He has won another power battle, just as he did with Cristiano Ronaldo. But since then, he has felt a tarnished figure: a reputation as a man who was tough but right was dented when players from Raphael Varane to Scott McTominay to Harry Maguire veered in and out of favour. A manager who seemed a pragmatic counter-attacker delivered a style of football that was bizarrely open; only in the Cup final triumph against City did he abandon his weird brand of anarchy.

Ten Hag professed himself unconcerned when a team who seemed to abandon the concept of a midfield allowed opponents absurd numbers of shots: 667, the second most, in the Premier League this season, 481 in all competitions in 2024, at least 20 in 16 games in the campaign. One theory was that, in trying to tap into United’s attacking traditions, Ten Hag had produced a warped version where too much of the considerable entertainment they offered was at their own expense. Another was that, tactically, they were completely incoherent, an object of fascination and amusement. They were the team who could go 3-0 up against Coventry and still need a penalty shootout. It does not generate much faith in his blueprint for next season.

Even above and beyond that, there were the bare facts: United had never finished below seventh in the Premier League before. They posted a negative goal difference for the first time since 1989-90. They propped up a Champions League group containing FC Copenhagen and Galatasaray. They lost to both, just as they lost to West Ham, Crystal Palace, Brighton, Bournemouth and Fulham, all deservedly. United’s away record against the top teams remained awful but while Old Trafford was a fortress during a 30-match unbeaten run, a litany of losses followed. They lost 3-0 at home in the Carabao Cup team to a weakened Newcastle team who started with six full-backs.

Meanwhile, Mauricio Pochettino was sacked by Chelsea after finishing sixth, with a better goal difference and without the European misadventures. As Louis van Gaal noted last week, he was fired by United despite winning the FA Cup: normally a failure to get a top-four finish has been a sackable offence at Old Trafford since Sir Alex Ferguson retired. Ten Hag did not come close to it. Despite the Wembley glory and the problems the injuries provided, he feels lucky to last for another year; United’s conclusion may have been that they could not find their ideal choice so are simply buying time.

Rewind to February and Ratcliffe said he wanted to populate Old Trafford with people who were “best in class, 10 out of 10s”. That rarely seemed to apply to Ten Hag this season. But after United’s worst Premier League and Champions League campaigns but their best FA Cup final in decades, they have belatedly decided he is the best man for next year.