Andy Robledo has been called “the dude doing the orange tents.”

And rightfully so. He has been providing the high-quality, bright orange tents to the city’s homeless population for about a year.

The striking temporary dwellings can be found at many of the city’s encampments: “Tent City” along the Dan Ryan Expressway at Taylor Street, on Canalport farther south, on Harrison Street to the north, near Ogilvie Station, and in Uptown.

Robledo said he began distributing the tents because he thinks the city has failed to provide housing for homeless people — instead keeping them on long waiting lists for permanent housing.

“These people die on these wait lists,” he said. “The red tape is killing people. ... I’m taking action where the city is falling short.”

But despite his work, the city is threatening to remove the dwellings.

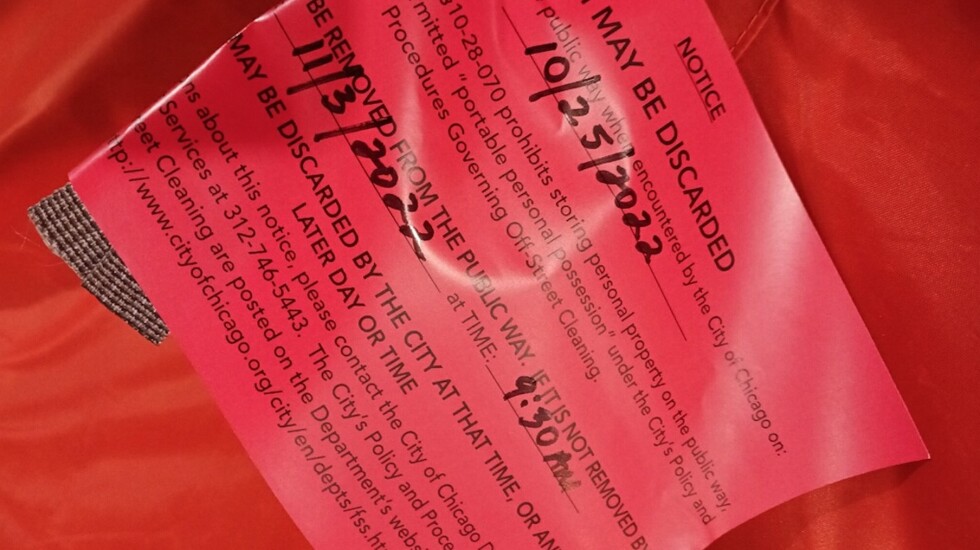

Tuesday morning, the city put removal tags on several tents at an encampment near Lake and Clinton streets, near Ogilvie, where Robledo said residents in nearby high-rises have complained. The tags say the city will remove the tents next week.

“They’re OK on the South Side, but they’re not OK ... next to luxury buildings,” Robledo said.

The tents, made for ice fishing, were chosen to help people survive Chicago’s frigid winters. Robledo has been buying the tents at more than $350 apiece with proceeds from his plant-delivery business and donations.

Robledo has faulted the city for removing tents from encampments, including one before this year’s Bank of America Chicago Marathon.

“This is how you do a ‘clean sweep’ @chicagomayor,” Robledo wrote in one video posted to social media, showing a newly cleaned camp with lines of his signature orange tents. Robledo said he’s set up the tents without the city’s help.

The city claims no one is relocated in the cleanings.

The removal tags are placed on items at the camps at least one week before the cleanings to warn the residents, according to a spokesman for the Department of Family and Support Services, which places the tags and makes efforts to connect the residents with shelter and housing.

“It is not illegal to be homeless in the City of Chicago, and DFSS keeps the rights of these individuals top of mind while balancing safety and hygiene needs of the entire community,” the agency said in a statement.

Robledo and residents from a camp explained that city workers only remove tents that are left unoccupied during the cleanings.

A former addict, Robledo said he sees himself in some of the homeless people he helps.

“They had lost everything. They didn’t have the support system that a lot of us had,” he said. “I would’ve been out there too if I didn’t have that.”

Homelessness is growing in Chicago.

The city estimates there were about 4,400 homeless people in Chicago last year, with 3,000 people in shelters and up to 1,400 people living on the streets.

The number of homeless people is considerably higher when including people in doubled-up temporary living conditions. The Chicago Coalition for the Homeless estimates the number of homeless people in the city increased 12% in 2020 to 65,000 people in all.

The cold and homelessness are a deadly mix. Sixty-four people died from cold exposure in Chicago between October 2021 and June 2022, according to Cook County medical examiner’s office data.

Homelessness in Chicago “is definitely getting worse,” said Ali Simmons, a street outreach and case worker at Chicago Coalition for the Homeless’ Law Project.

Evictions and lack of affordable rent are behind some of it, Simmons said.

Simmons faulted Mayor Lori Lightfoot for not keeping a campaign promise to implement a real estate transfer tax on homes worth more than $1 million to fund homelessness programs.

“It’s the city’s problem. They haven’t addressed this in a sensible manner,” Simmons said.

Robledo said he’s stepped in where authorities have failed homeless people.

He overcame alcoholism three years ago, grew tired of his job in the corporate world and “wanted something more,” he said.

Robledo, 37, began a side business delivering plants from his pickup truck. He quit his corporate job after the pandemic struck.

“It was the perfect opportunity. I was out delivering plants every day. I saw lines at food pantries, and it broke my heart,” he said.

He used profits from the plant business, Plants Delivered Chicago, to provide food for the city’s homeless population, something he continues today.

Then one day, someone broke into his truck and stole — not the money or valuables inside — but a blanket.

He found that blanket draped over a wheelchair at a homeless camp nearby and told himself, “I need to take some action.”

He began delivering blankets and food to camps across the city.

Then, last winter, he paid for 20 homeless people to stay at a hotel for two weeks. When they returned, all of their tents had been destroyed by heavy snow.

“I was thinking, ‘How can we build this back better?’” Robledo said.

He got the idea for using sturdy ice fishing tents from a pastor in Minnesota. With the help of a carpenter who was once homeless, they built foundations for the ice fishing tents, which naturally had no bottoms.

The tents are more suitable and rat-proof than camping tents, residents said at the camp in East Pilsen along Canalport under the Dan Ryan Expressway.

“The tents right here, they’re a big help,” said Henry Thomas, 51. “These can handle the wind and the weather a lot better.”

Another resident, Eddie Payton, said the city trashed his tent a couple of weeks ago during a sweep at the Canalport site while he was away visiting family on the South Side for the weekend.

“I was hurt. I was in shock,” said Payton, 66. His destroyed tent had been propped up on wooden pallets.

But he was soon given a replacement tent from his neighbors at the camp, which he called a “community.”

Now Payton, originally from Mississippi, has an orange tent that’s much roomier. Inside he organized his belongings near a small table.

“I’m overwhelmed,” Payton said about his new orange tent.

Robledo has recently provided six tents in Uptown, around 10 on Canalport and 10 near Lake and Clinton. He’s gotten only positive responses from people who live near most sites, except for two locations in the West Loop and Logan Square.

“We had some neighbors asking, ‘Why are you helping them? You’re making it worse,’” Robledo said. “They likened it to a rat problem. These are humans. This could be your brother.”