The Creator is an incredible movie, and now it's Oscar nomination for Best Visual Effects has put this sci-fi fable back at the top of our must-view lists. The Creator delivered some beautiful and evocative sci-fi imaginary and it did it on a smaller budget that most genre films. How was it done?

Filmmaker Gareth Edwards made his name by creating the VFX himself in Photoshop for his movie Monsters and went on to direct Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. The Creator in many ways takes the director back his roots as a visual effects artist, searching for new ways to innovate on a smaller budget. (For example The Creator has a clever VFX detail have brings its androids to life.)

"I was happiest as a person doing visual effects," admits Gareth. "Making films is crazy stressful. Someone gives you tens of millions of dollars and then you have to promise to give it back as a profit a few years from now; it's quite a trick trying to pull that off."

Streamlining the shooting process is the fact that Gareth acts as his own camera operator. "There are probably a few reasons why I like to hold the camera," he says, "but in terms of visual effects one big reason is that in a science fiction movie, 30% of what's going to be in that final shot isn't actually there.

"We've always tried to have something represent what would be there. But when you’re trying to have a director of photography or camera operator understand how a ship is going to come in to land, slightly settle with its legs coming out, and framing it all perfectly as if it's happening, it can become frustrating as they're not imagining it how you're imagining it. The other thing as well is we wanted this thing to feel naturalistic and organic, and slightly a hybrid of a documentary meets a James Cameron movie."

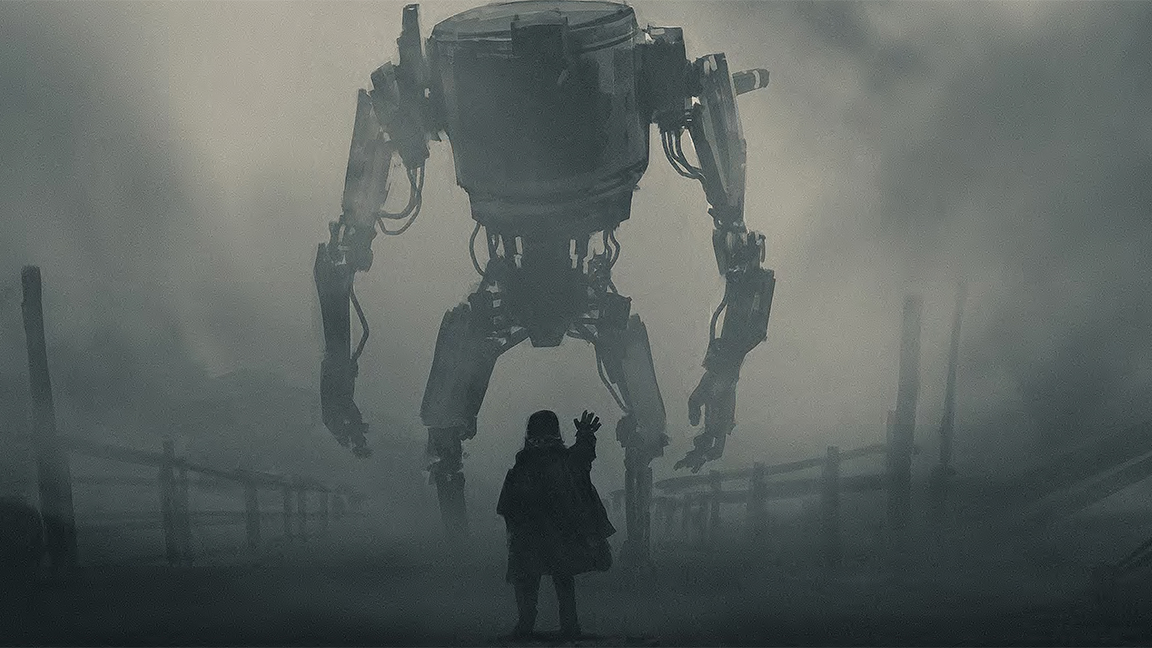

The Creator revolves around a former special forces operative who is recruited to kill the architect of an advanced AI and capture a mysterious weapon of mass destruction created in the form of a child. "Because The Creator was an original IP, Gareth and I wanted something new," remarks James Clyne, the production designer.

"What that meant was we weren't trying to predict the future, rather we were trying to create our own future. We can be influenced by Akira or the first Blade Runner, and mash some of these influences and make our own thing out of it.

Making films is crazy stressful. Someone gives you tens of millions of dollars and then you have to promise to give it back

Gareth Edwards, director

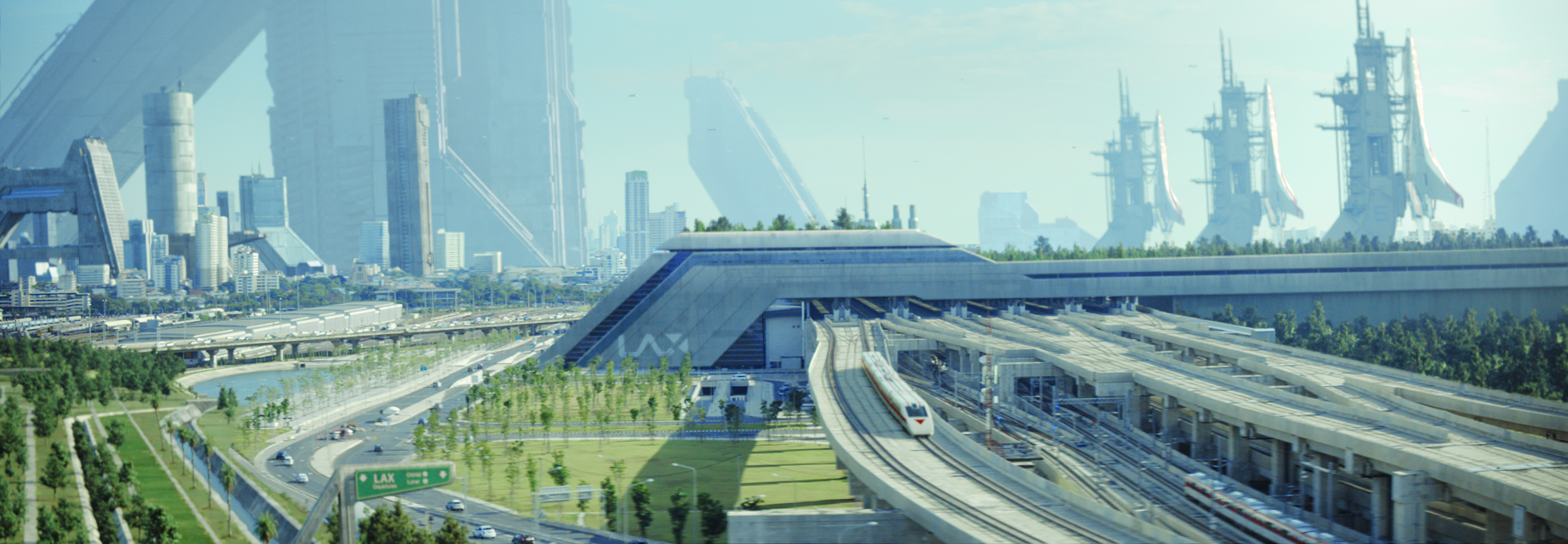

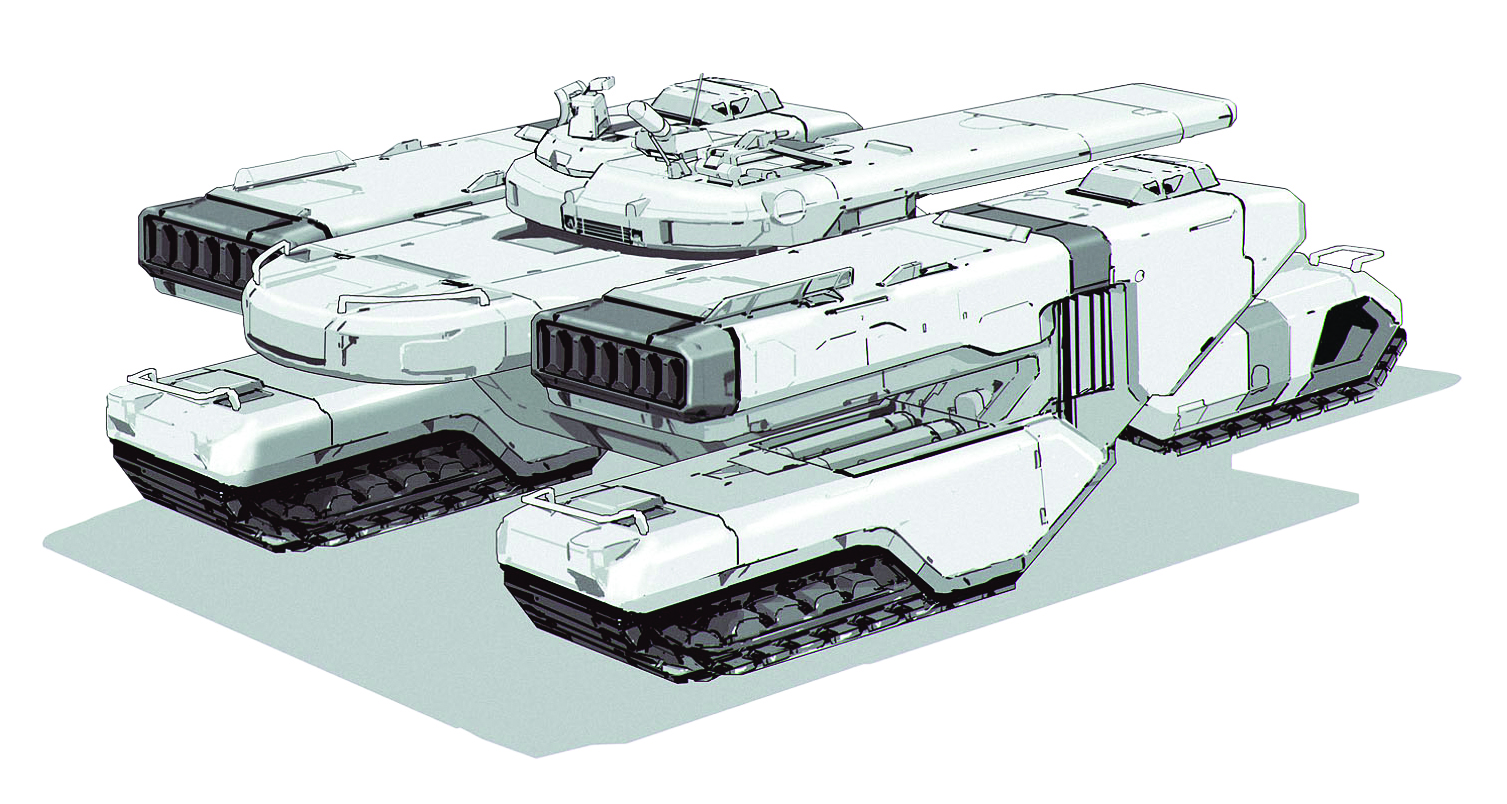

"A lot of it was Gareth and I asking, 'What's going to make a cool-looking shot and design?' We're both into graphic design. The buildings, for example, I didn't want them to be these tall pillars. Why can't they just go across horizontally and then drop back down? As far as cars go, a lot of it was looking at historical technologies like Japanese Walkmans and what if that was a car.

"We loved the industrial design of the 1980s and 1990s. It was blocky and real buttons. It worked for us cinematically where things were more tactile and less digital, transparent images. An iPad is one of the most boring props you can put into a movie because it's like a piece of glass, plastic and metal in a perfect frame. We tried to do things that had interesting shapes, and were complicated and fresh."

AI-human hybrids known as Simulants, portrayed by Madeleine Yuna Voyles and Ken Watanabe, have the bottom half of the cranium, ears and back of the neck replaced with intricate robotics. "I didn't want any dots on anybody because I didn’t want to spend time doing that," says Gareth. "Also, I was paranoid that if Alphie [Voyles] had a hood on and dots all over her face, what wasn't a visual effects shot would become one. ILM sneakily put in some dots. I remember on day one filming I noticed a freckle that I'd never seen before on her nose.

What I'm most proud of, which was probably the most painful thing that's in nearly every shot, is that we didn't have all of the data that visual effects would have wanted

Gareth Edwards, director

Afterwards I said to the make-up woman, 'Did she have a freckle there?' She said, 'No. We put that on for visual effects.'" Adding to the complexity was the lack of any on-set references. "What I'm most proud of, which was probably the most painful thing that's in nearly every shot, is that we didn't have all of the data that visual effects would have wanted," Gareth adds.

"There's a thrown away naturalism to some of the plates and shots," remarks Gareth. "But when you actually figure out how to do it, the visual effects feel 10 times more real because it all affects each other. The audience doesn't know what ILM did and what was really there."

Much of the concept art was not fully realised going into postproduction. "It's not every pixel where it needs to be," says James. "It's more broad strokes. Part of the thing that never happens, or rarely happens, is that I was still part of post-production as the production designer, so we had a certain level of confidence that our little sketches and rough ideas would eventually get ironed out, because I'd be able to oversee it on the backend."

The Creator's world-building was driven by 80 locations across Thailand, Japan and Nepal. James adds: "The hope was to shoot all over Southeast Asia, but because of COVID-19 we couldn’t as it meant having to quarantine for two weeks between each country."

He also recalls many stunning locations found in Thailand. "We shot at Railay Beach for the opening scene, found a rice factory outside of Bangkok for a section of our underground lab where we first see Alphie, and shot a train station that's part of the NOMAD. In Bangkok we had this beautiful location in a high-rise that was a nightclub, which was used as Drew's apartment. It had this huge slanting wall of glass on one side that looked outside at Bangkok, which looked like this cool futuristic city at night. Using the strength of the location, we put a megastructure way back in the distance and kept all of the Bangkok stuff in the foreground."

It's a scary place to be as a visual effects supervisor, to not know what you're building until you start seeing the art

Jay Cooper, VFX supervisor

Responsible for over 1,600 visual effects shots created by ILM, MARZ, Atomic Arts, Folks VFX, Fin Design + Effects, Outpost VFX and Crafty Apes was production VFX supervisor Jay Cooper.

"It's a scary place to be as a visual effects supervisor, to not know what you're building until you start seeing the art," he states. "James would do a number of proposals of different building structures and then we would get something up on its feet. We would go back and forth iterating to find something that was to Gareth’s liking. It was really, 'This is what we have as a starting point. How can we turn this into something cool? What parts can we leverage from the plate and what parts have to go?'"

Complicating matters on a number of fronts was Gareth Edwards doubling as the camera operator. "In the shoots I've worked on in the past, you’re trying to pick up a shot, so either you're working with a storyboard or a piece of previs," Jay adds. "Gareth's approach is to try to find more interesting compositions and play with some of the staging as well as performances in real-time. In terms of what that means for visual effects is that part of the shot you wouldn't expect to see is now part of the shot, or there are characters present that you didn't expect."

Then there was the challenge of creating the film's Simulants. "There are absolutely huge portions of these actors where we're either re-projecting what was originally there, or are blending our own CG version of our character in with the photographic version," Jay says. "Every time we're doing a Simulant shot, we're using portions of our renders or plates, and re-projecting parts of the plate to try to get it all to sit together."

A variety of complex shots had to be executed during the course of production. "I'll give you one shot that I really like, which has a bunch of robots in the crusher," Jay states. "The plate for that was a construction yard, then Gareth or James did draw-overs and said, 'Why don't we turn this into a crushing mechanism?' And we had to drop hundreds of robots in it. We had to figure out how to simulate and crush them. Then we did additional animation on top to have robots crawling out of the scrum.

"That's a shot that I absolutely love because it has all the things I liked about working on this project. We started with a real location, had a real idea of what the shot was going to be – there's no shot without the visual effects – then we brought our resources to bear to do this expensive and complicated simulation, and have all these things crushed together.

"We brought in additional animation to help communicate all the beautiful horror of this moment. There are a number of times where that was the goal of the storytelling, as Gareth wants the audience to think about how much humanity there is in each of these AI robots."

Making The Creator: guerrilla tactics

Gareth Edwards hasn't altered his indie sensibilities despite directing two Hollywood blockbusters in Godzilla and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story.

"We had a tour a few years ago in a virtual studio in Los Angeles and on the wall was this giant poster, which showed the process of how you make a film, like a node diagram," recalls Gareth Edwards.

"It was such an obvious thing about how you write a script, shoot and edit. It hit me how little has changed in the last 100 years. We have all these amazing digital tools at our disposal, but still go about the process of making a film like we did in the 1920s. Personally I think the process is wrong, or at least there are other ways of doing it. With every movie I’m always fighting that.

"On The Creator I was lucky they let us shoot a lot of it in a more guerrilla-efficient way. Hopefully the movie looks like we spent a crazy amount of money on it. We ended up working backwards.

"Normally what you do is design the world, show the studio, someone budgets it and says, 'This is going to be $200 million. And the only way you can possibly film it is against green screen and do all of the effects.' I was like, 'I don't want to do that. We want to go to real places in the real world, shoot as if it exists, everyone imagining everything there, come back and edit it, and when we've got the edit finished we'll design it.' We'll sit down with frames from the actual film and paint over them per shot, give that to the VFX company and say, 'Make a photoreal version of this.'"

Making The Creator: using StageCraft

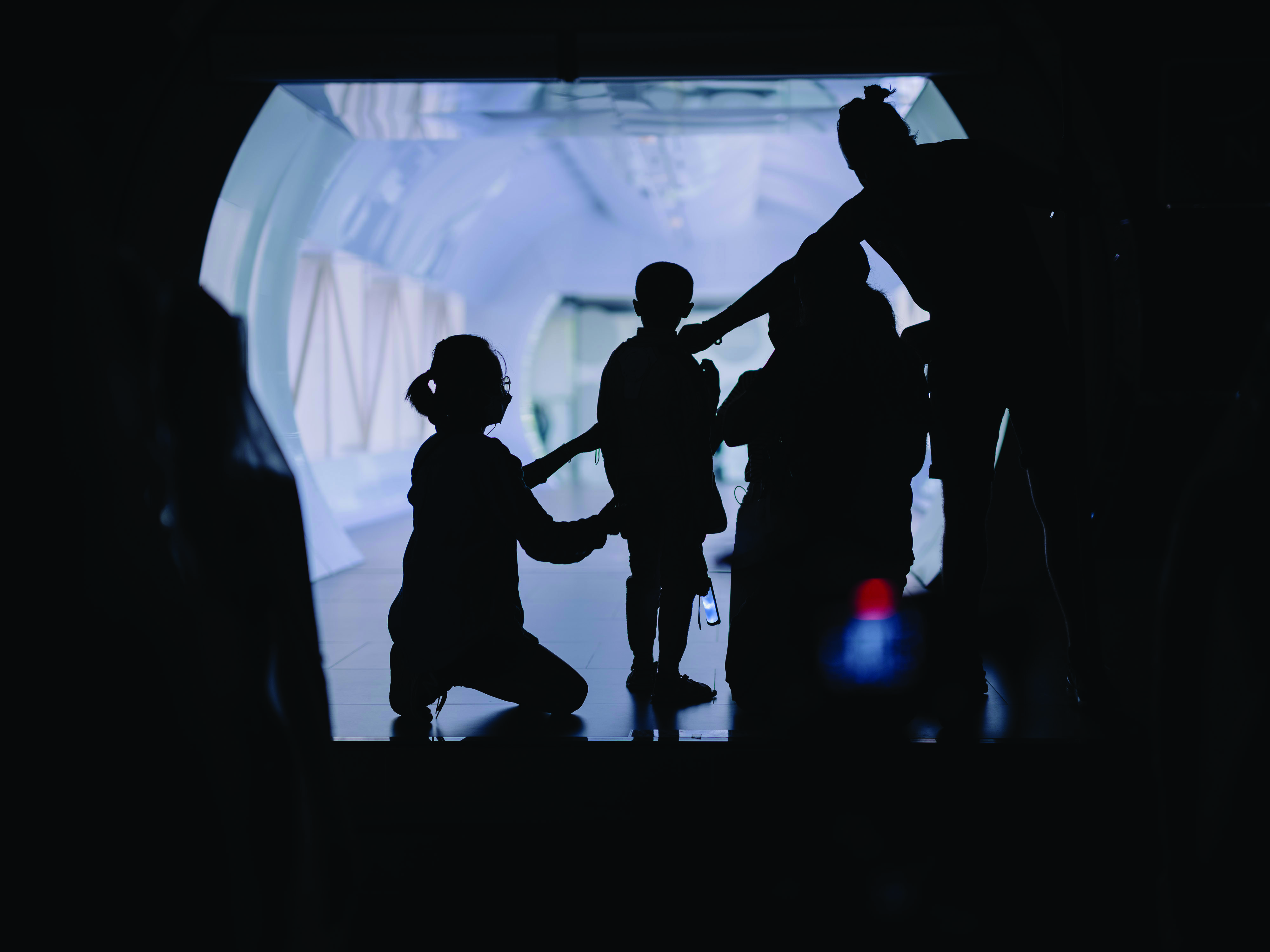

Scenes involving the USS NOMAD's airlock, escape pod and biosphere were captured using StageCraft.

Time was of the essence when shooting in the virtual production stage. "We had big pieces that needed to get into the volume quickly," explains Shira Hockman, the supervising art director. "It was figuring out what was possible to build in the time given, and then how to break it down into pieces that we could literally wheel in on the day and bolt together.

"We also had two companies working on that set. We had Supersets building the airlock and gantry, then we had BGI Supplies doing the escape pod door at the end. Then Supersets did the interior of the escape pod and BGI Supplies did the rails, so it was making sure that all of the pieces coming from both companies were going to fit together and work.

"In the case of the airlock door, it was a hugely detailed piece and the process making that out of fibreglass is a lengthy one. There was massive constraint on getting our 3D files to be robot cuts so that we had great big foam masters of the door, then mould and cast that, and then that had to get finished, painted and have a huge steel armature. We were lucky, because the way that BGI Supplies engineered the airlock door it could be automated to be opened in camera."

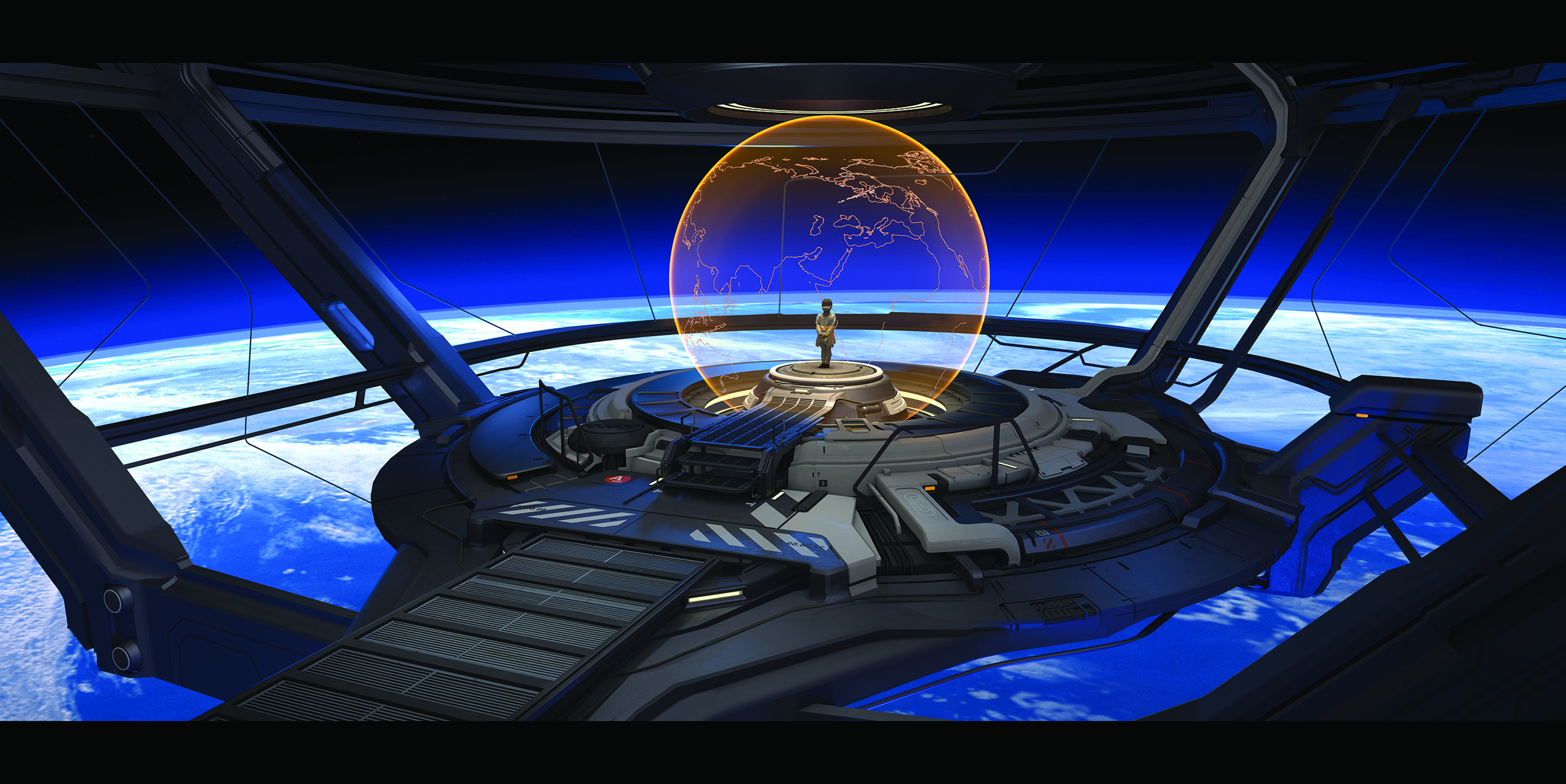

Making The Creator: conceptualising the USS NOMAD

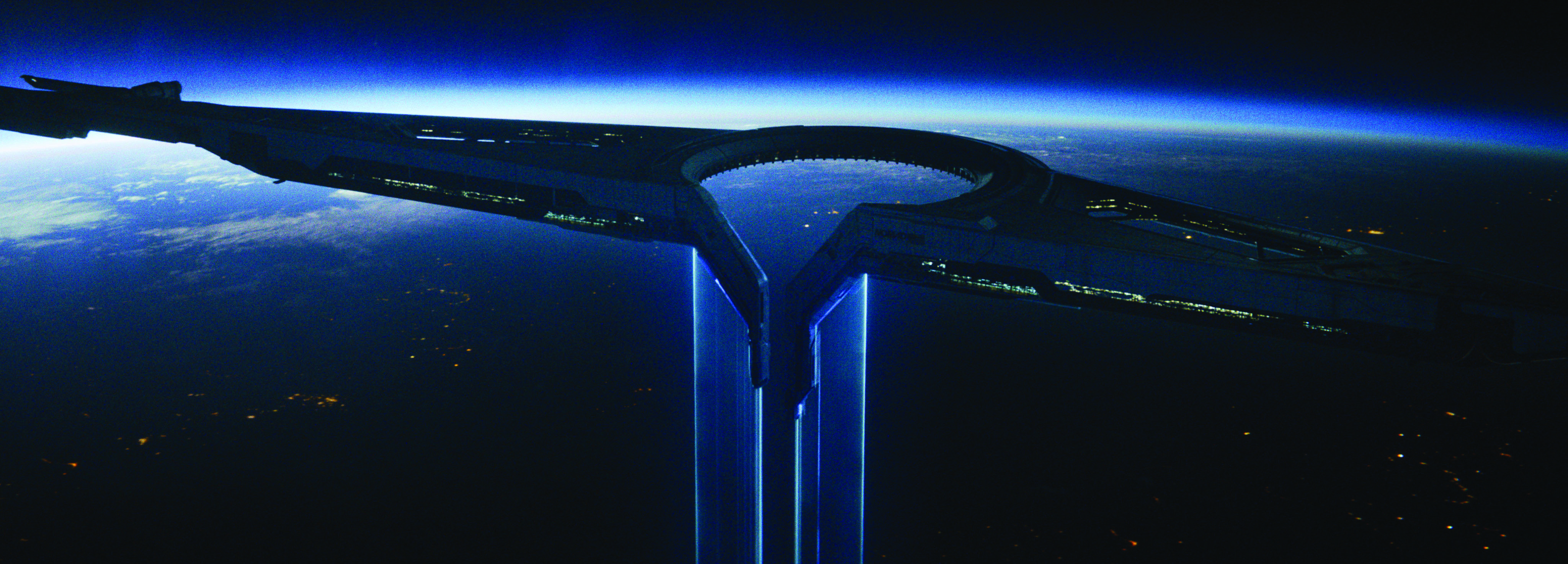

A major design task was conceptualising the USS NOMAD space station setting for the third act.

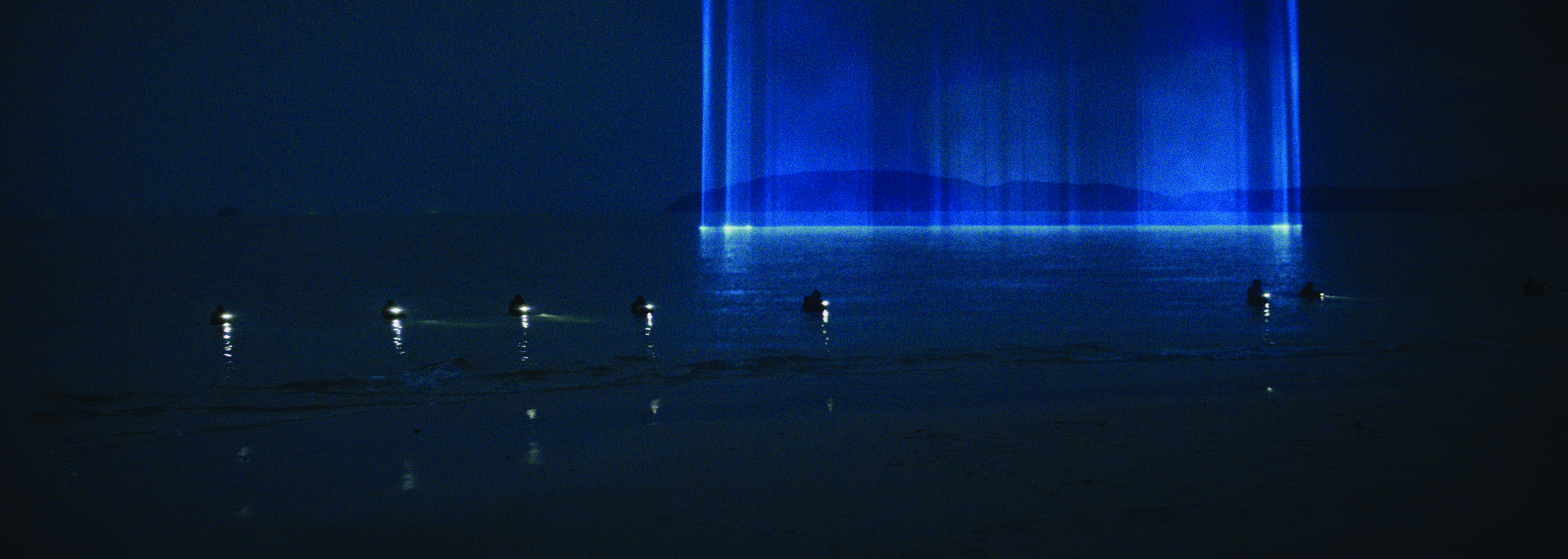

Questions were asked about the look and functionality of the American space station NOMAD (North American Orbital Mobile Aerospace Defense). "Gareth had certain ideas that he wanted where it shoots a targeting beam on villages and acts as a target for weapons, but also to show the way for these soldiers," says James Clyne.

"As far as the shape, we went through hundreds and hundreds of little sketches and ideas. We finally came across this idea of a bird of prey, almost like a circling hawk and how that would look in the sky. The design had to feel primal and make you anxious when you see it circling like that.

"Once we had that as an idea it was easy to lock into our look. I sent Gareth an image from Pink Floyd’s The Wall of a circling blackbird and he got curious; that was the jumping off point for that design."

This interview originally appeared in 3D World magazine, the world's leading digital art, CG and VFX magazine. 3D World is on sale in the UK, Europe, United States, Canada, Australia and more. Limited numbers of 3D World print editions are available for delivery from our online store (the shipping costs are included in all prices).