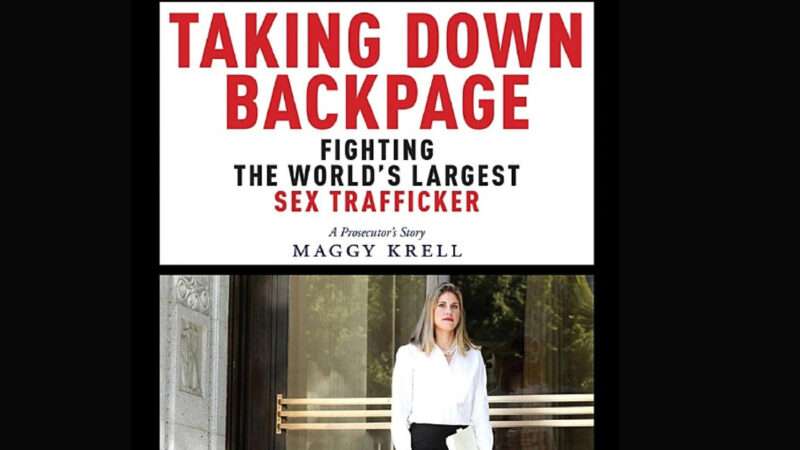

Former California prosecutor Maggy Krell has been taking an undeserved victory lap over the demise of Backpage. She has a new book called Taking Down Backpage: Fighting the World's Largest Sex Trafficker, and Krell has been making the media rounds promoting it. But the case Krell worked on didn't really "take down Backpage" or prove the site guilty of sex trafficking. Indeed, the pimping charges she helped bring against Backpage's CEO and founders were twice thrown out of court.

Krell was part of a 2016 case signed off on by future Vice President Kamala Harris, who was then California's attorney general and was running for the U.S. Senate. A few days before the 2016 election, Harris and Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton earned nationwide press when they charged Backpage CEO Carl Ferrar and company founders Michael Lacey and James Larkin with pimping and conspiracy to commit pimping.

Their case rested on the fact that some people used the classified advertising platform to facilitate sex work. But because Backpage was simply a conduit for third-party speech—much like Craigslist, Facebook, or Twitter—a judge quickly dismissed the case.

A few weeks later, Harris, Krell, and their colleagues again brought pimping charges against Ferrar, Lacey, and Larkin. Again, a judge threw them out.

This second time, the judge did allow prosecutors to proceed with money laundering charges. Ferrar would eventually plead guilty to money laundering in 2018, as part of a deal that helped him avoid more severe federal charges. Krell had already left the state attorney general's office by this point. The money laundering charges she helped bring against Lacey and Larkin are still on hold, while a case against them winds its way through federal court.

It's that federal case that led to "taking down Backpage": In 2018, federal law enforcement agencies seized Backpage.com and affiliated websites. The feds do credit the California attorney general's office with "participating in and supporting" this enforcement action. But like the California case, the federal case does not involve charges of sex trafficking.

It's also not over. After years of delays, the trial of Lacey, Larkin, and other former executives (minus Ferrar, who took that plea deal) finally got started in September 2021. It resulted in a mistrial, with the judge declated that the feds weren't playing by the rules.

A new federal trial was supposed to start in February, but it's been postponed as the parties battle over whether the case should be totally dismissed. In December, a district judge dismissed defendants' motion to dismiss; they responded by appealing to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Perhaps Krell's book was written with the idea that, by this point, the Backpage defendants would have been found guilty and she could soundly claim at least some part in their "takedown." But that didn't happen. In any event, California's contribution to the case is questionable. Testifying at the federal trial last September, California Department of Justice Special Agent Brian Fichtner—the man who wrote the affidavit that Krell's charges were based on—arguably did more to help the defense than his own team.

Fichtner was there to present Backpage ads that he and federal prosecutors deemed to be clear evidence of illegal sex work, since a big part of the case turns on whether Backpage execs knew or should have known that some ads were facilitating prostitution. But Fichtner ended up admitting that none of the ads he presented directly offered sex for cash, none could be considered definitive solicitations for prostitution (as opposed to some sort of legal sex work or relationship), and none of the ads alone would be enough to justify a prostitution arrest.

Krell (in her book) and Fichtner (in his affidavit and at trial) have both made a big to-do of what may be the dumbest stunt in the whole decade-plus persecution of Backpage. The cops posted to Backpage an ad featuring the picture of a woman Krell describes as "young" and "sexy" and a solicitation "Let's party together, you'll leave with a smile." They received hundreds of replies from men eager to meet her. They also posted an ad offering a used couch for $150, and received no replies. This is somehow supposed to prove something beyond "sexy women get more attention than old couches."

A recent New York Daily News article about Krell's book claims the ad "promised sex with a teenager," though it neither promised sex nor featured a teenager. The woman pictured in it was an adult, and the age listed on the ad was 24.

Krell herself does not offer so bold a falsehood. But in promoting her book, she has said plenty that's misleading. For instance, in an interview with NPR, Krell insists that Backpage "never did anything to prevent sex trafficking." In fact, the company banned explicit offers of sex for money, had extensive steps in place to try to prevent ads posted by or for minors, voluntarily worked with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) to refine these procedures, and was described by federal prosecutors in private memos as "genuinely want[ing] to get child prostitution off of its site."

"Witnesses have consistently testified that Backpage was making substantial efforts to prevent criminal conduct on its site, that it was coordinating efforts with law enforcement agencies and NCMEC, and that it was conducting its businesses in accordance with legal advice," wrote prosecutors in 2013, noting that their investigation failed "to uncover compelling evidence of criminal intent or a pattern or reckless conduct regarding minors." And "unlike virtually every other website that is used for prostitution and sex trafficking, Backpage is remarkably responsive to law enforcement requests and often takes proactive steps to assist in investigations," they wrote.

Krell does admit to NPR that Backpage helped solve criminal cases by working with law enforcement when ads were suspected to facilitate forced or underage prostitution. (Ferrar even got a certificate from the Justice Department commemorating his work.) However, she still thinks the site should've been shut down because these bad actors were able to post there.

This sort of logic only works if you think that without one particular web platform to communicate on, predators will just give up on predatory activity. But both common sense and real-world evidence tell us that this doesn't happen. Instead, criminals migrate to other digital platforms—including those that are less public (and thus harder for law enforcement to monitor), less willing to work with law enforcement, and/or not subject to U.S. laws. Or they take things offline, forcing victims to work the streets and not leaving a paper trail.

Krell's logic regarding Backpage is in keeping with her other efforts to punish entitites that facilitate sex work, even when those involved are willing participants. Prior to bringing charges against Backpage, Krell criminally charged a motel where prostitution took place with pimping and conspiracy to commit prostitution. Krell also seems to support going after social media companies because bad actors can communicate through them. Facebook "can't stick its head in the sand" about sex trafficking, she told USA Today last October.

If this book tour keeps Krell out of the courtroom, maybe its not such a bad thing after all.

The post Maggy Krell Repackages Her Bogus Backpage Prosecution Into a Book appeared first on Reason.com.