Fears of a 30-hour queue to see the Queen’s lying in state have not yet come true, but the wait is still considerable.

Having joined the queue at Blackfriars Bridge just as dawn broke at 6am on Thursday, it took until 10.30am to travel the two miles to Westminster Hall and the Queen’s coffin.

Our fellow queuers were a varied lot. Some had dressed casually and wrapped up against the early morning cold, others wore the traditional black suit, while ex-forces personnel came with medals and berets.

One mourner donned a bowler hat, pinstriped suit and furled umbrella, like he had come straight from George VI’s lying in state in 1952, images of which were beamed onto the side of the National Theatre.

In some ways, the queue has become an event in itself, something passing joggers filmed on their phones and the world’s media sent cameras to capture, while on social media questions about waiting times poured in.

The wait is difficult to gauge, and the queue can sometimes be deceptive.

From Blackfriars it moved steadily, reaching Waterloo Bridge in an hour and then picking up pace past the London Eye and down towards Lambeth Bridge.

But it is here that the real queuing begins, over the Thames and then back and forth through Victoria Gardens for nearly two hours.

Muscle aches set in, morale begins to flag and queuers discard the food they brought with them but fear they no longer have time to eat. That food, collected by the Scouts, is either redistributed through the queue or sent to a local foodbank.

But all that waiting offers ample time to chat with some of the thousands of mourners who have come to pay their respects.

Some conversations focused on work, hobbies and, later on, the ache of standing in a queue for so many hours, but mostly people talked about the Queen.

There were those who had seen her themselves, not just in the UK but abroad too.

One man, brought up in Trinidad and Tobago but now living in London, told me how she had passed his house during a visit to the Caribbean and said he and his wife had now come to thank her for her “long years of service not just to Britain but all of the Commonwealth”.

Others came to be part of history, to see a once-in-many-generations event, while others felt drawn by some undefinable connection to the Queen, even if they did not support the monarchy.

Despite being “not really a royalist” and never having seen the Queen in person, 70-year-old Andrew Halas said he felt “somehow, indelibly, she has made a connection with people of my generation”.

Everyone uses the same word to describe the Queen – “constant”.

But once inside, the talking stops.

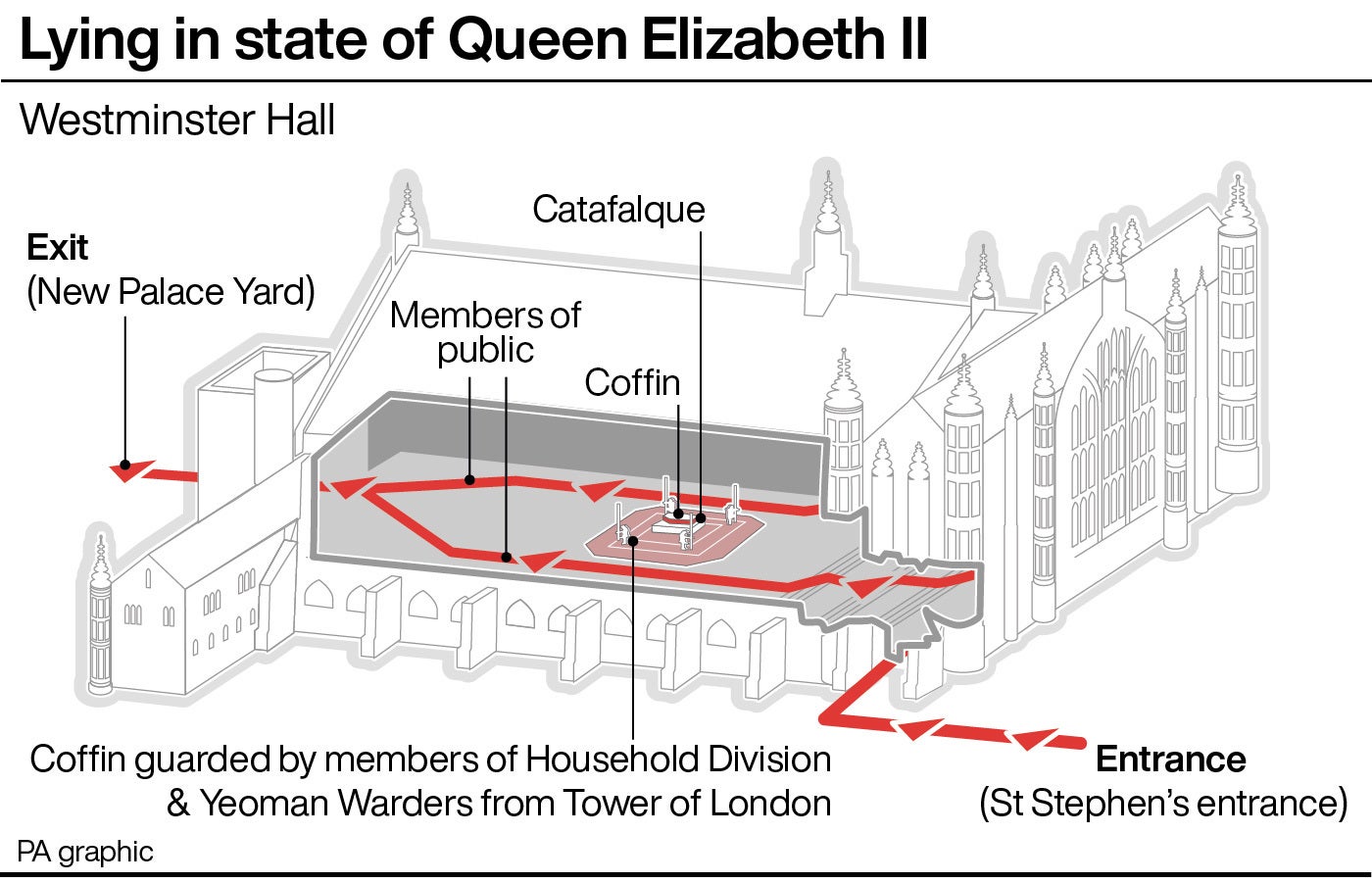

It is an eerie hush that has enveloped Westminster Hall – usually a place of noise and clutter as tourists and school parties are directed from information desks further into the Palace of Westminster.

Now, the vast Norman hall is dominated by the Queen’s coffin, draped in the Royal Standard and surrounded by guards, who are as still as waxworks.

As we file through the hall, we witness a Changing of the Guard. Co-ordinated by a series of taps from the Officer of the Watch’s stick, a new round of Irish Guards, Beefeaters and Gentlemen at Arms takes its place next to the old guard.

Two more taps, and suddenly the old guard seems to leave its trance and return to life, marching off while the new guard bow their heads and fall still.

The mourners begin filing past again, each paying respect in their own way. Some bow or curtsey, some pray, some shed tears.

But at the end, as they leave Westminster Hall, most take one final look back at the coffin, a last glimpse of our longest reigning monarch.