“Video games are multidisciplinary,” writes Simon Parkin in Game Changers: The Video Game Revolution, a hulking coffee table tome from 2023 chronicling the many captivating experiences devised for this medium. “They typically require the eye of an artist, the ear of a musician, the pen of a writer, the purpose of a designer, and the logic of a programmer,” states the foreword to the book.

Remarkably, Lucas Pope is all of these things. As a result, he has earned a reputation as independent gaming’s pre-eminent icon. In 2013, Pope singlehandedly created and released Papers, Please, following it up with The Return Of The Obra Dinn five years later. The former charged players with the role of a border-crossing officer, deciding the fates of a beleaguered legion of immigrants in the imagined, dystopic Cold War-era totalitarian state of Arstotzka. The latter rewound to the 1800s, catapulting players onto the deck of an East India Company ghost ship and asking them to unravel – for insurance purposes – a deathly mystery.

Described in a recent FT interview as a “designer of idiosyncratic games”, Pope has now ventured into space with Mars After Midnight, a new offbeat caper released exclusively on the Playdate handheld games console. What made him decide the canary yellow handheld – built by Panic, the developer and publisher of Firewatch and Untitled Goose Game – would be an ideal vehicle for what is described as “an entrant-screening, mess-tidying, session-planning, Martian-filled game”?

Toy story

“I first saw the Playdate when everyone else did,” Pope tells us of the 2019 reveal from the Portland-based company, which he describes as a “jackpot” moment. “I was coming off Obra Dinn. Anything that's 1-bit is right up my alley and then I saw the crank. Everything made me think: ‘This is awesome. I want to make a game for it’,” he explains. After getting his hands on one of the devices at a gaming event in Japan - where Pope lives - Panic sent a pre-release piece of hardware to tinker with.

“I’d played Firewatch and Untitled Goose Game. But I wasn't looking for a publisher. I was excited about the hardware,” says Pope, praising the Sharp LCD screen and design managed by Teenage Engineering. “I wanted to take a look and maybe try to make something or experiment with it. I didn't give them any promises, say I was going to make a game, or had big plans.”

There's a lot of expectation attached to anything I do now. There's a lot of pressure following up Papers, Please, and Obra Dinn

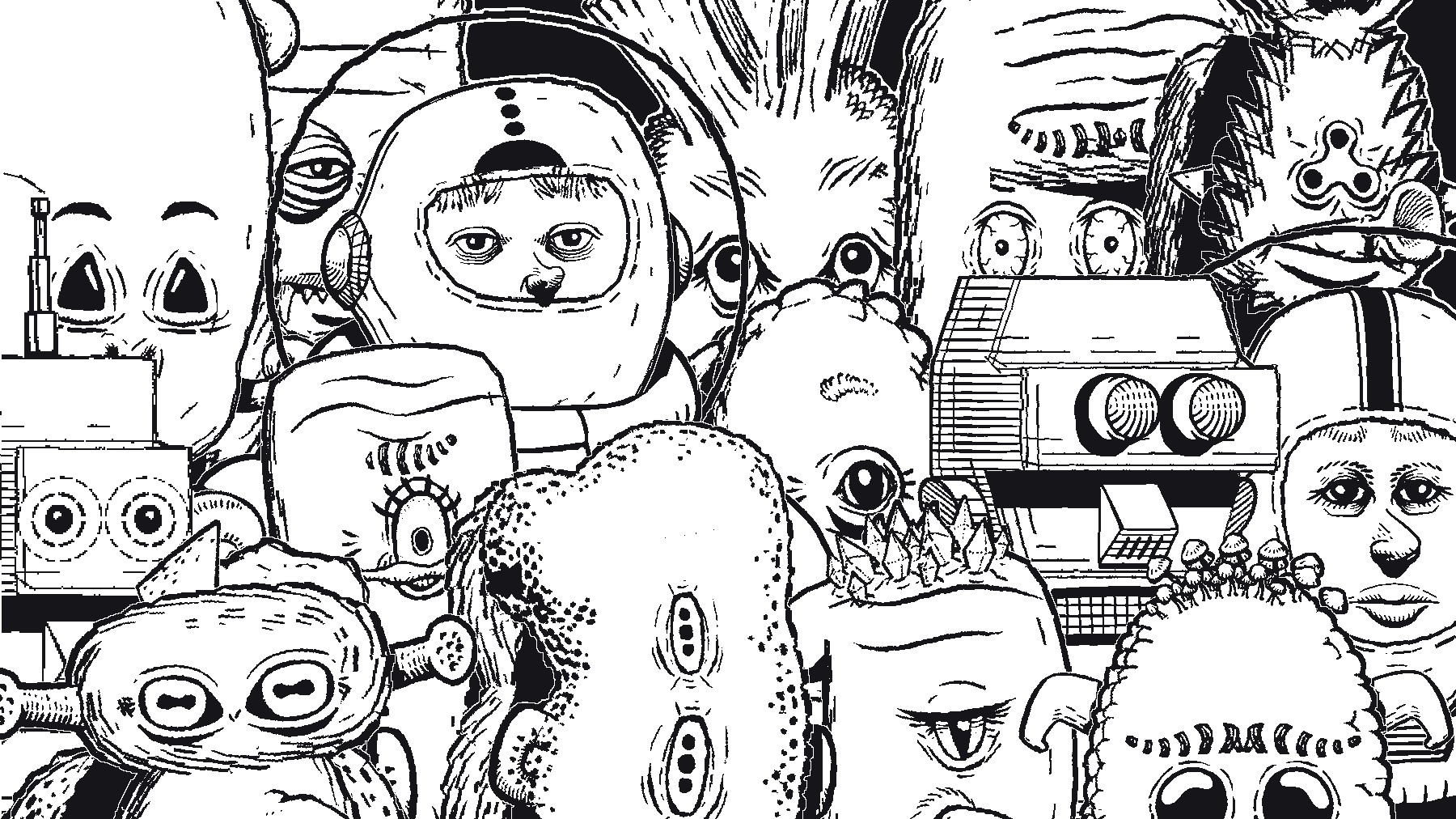

Released earlier this month, Mars After Midnight is the long-awaited result. It’s an experience containing many of the quirky - and magnetic - hallmarks that have established Pope as a leading figure in his field. Featuring a rogue assemblage of procedurally generated aliens with shirty faces, the player is transported to “the Red Planet” - here cast in Playdate’s high contrast black and white - to run a late night/early morning community center. Because, of course, even in space, aliens have issues with anger, bad skin, and flatulence. Hilarity, inevitably, ensues.

The game begins with the tribute “For our kids” and Pope suggests his instincts around the technology triggered a deterministic way forward. “When I got the Playdate, I felt like it was the perfect thing for my kids to be playing,” he says. “It's frustrating to have children who are crazy about games but can't play my games. They’re too violent, too mature, and just not interesting. I wanted to make something for them. I thought: ‘OK, cartoonish faces – I can do the drawing for that.’ Plus, putting them together procedurally gives a lot more flexibility if they're not supposed to represent real faces.”

Life on Mars

Using the device’s attached crank as a window shutter - in tandem with a familiar set of “rote mechanics” - allowed Pope to open up the scope of the experience beyond the handheld’s 2.7-inch screen, providing a zoomable frame through which events are – for much of the three-hour runtime – drawn. It was here that his multidisciplinary skills came to the fore. “I didn't know what the game was for three years,” he admits. Two of these were spent illustrating the collection of disfigured mutants that populate the “off-colony settlement”.

“I was building the pieces up thinking there was probably a good game in there but with no real pressure to put it together. The pandemic slowed me down mentally and physically. I worked on it for a long time without making a whole lot of progress. It wasn't until six or seven months ago when I finally decided I had to get it to a point where you could play it. That was when I started putting everything together and adding the bits in between and the mild narrative that runs through,” he continues.

What are his aspirations for Mars After Midnight? “There's a lot of expectation attached to anything I do now. There's a lot of pressure following up Papers, Please, and Obra Dinn, and making something else that everyone's going to love. With the Playdate, it lowers the temperature on that expectation, especially because I made it clear this is a game I'm making for my kids, which is aimed at kids. That part is worth a lot more than just money or sales,” says Pope. Happily, his children “love” Mars After Midnight.

As a designer, Pope fully accepts he is driven by a desire to create “weird” titles, using fastidious levels of detail that target the player’s deeper imagination rather than their base emotions. Raised in the US state of Virginia, where he studied mechanical engineering, this proved to be one of the defining motivations behind Pope’s decision to quit a development role at Naughty Dog in Los Angeles, after working on the Uncharted series, and move to Saitama, near Tokyo.

Awards, Please

Papers, Please was self-published by his production company 3909 LLC. It confirmed the emergence of a creative figure who was much more interested in “flipping the concept and the cliché on its head," focusing on the forks in the road - and the places they take gamers - rather than the straight route ahead. “There's plenty of great games where you're shooting people the whole time. If you're going to be interested in my games, it's hard for me to do the same thing everyone else is doing and stand out. I prefer different interactive experiences. Something new, something I haven't played before.”

Return Of The Obra Dinn was exactly that. Like Papers, Please it proved to be a universal hit with critics. Both won the Seumas McNally Grand Prize, the main award at the Independent Games Festival (IGF). Pope explains how the seafaring title developed from the kernel of an idea centered on the real-world East India Company, which managed English trade in the Indian Ocean region between 1600 and 1874.

Obra Dinn was a tricky one because it's a very passive game.

“Pirates are popular. Everybody loves them. There are lots of movies and media about pirates, including games. But when I started to read the true accounts people wrote about shipwrecks, that vibe was really not present. The real stories were very unromantic,” he explains, pointing to the collection of desperate and dastardly tales captured in Remarkable Shipwrecks; Or, A Collection Of Interesting Accounts Of Naval Disasters. “I thought that was so interesting and wanted to get a nugget of it.”

To achieve this, Pope devised an ingeniously engrossing “deductive setup” to determine the identities of all 60 passengers on the ship’s ledger. “Obra Dinn was a tricky one because it's a very passive game. When you're making a game for audiences today, you have to think about how much killing people want to do. It's usually a lot. Obra Dinn was another flip the script thing. Instead of doing the killing, you have to watch it. You have to figure out all the details, get your nose up in there, and figure it out. But you're not pulling the trigger, ever,” says Pope.

‘Games bring all the things I love together’

Game Changers: The Video Game Revolution charts the course of 260 landmark titles - both Papers, Please, and Return Of The Obra Dinn feature - across 70 years and 20 consoles. The selected biographies focus on 29 of the most influential figures in the chequered history of the industry: Pope is one of them. Equal parts artist, musician, writer, designer, and programmer, chatting to him reveals a pragmatic mindset and provides an intriguing insight into his processes.

“It sounds bad that I have to do everything myself but it also means there's no skull barrier between the ideas. It doesn't go from my brain, through my skull, to someone else's and into their brain. There's nothing there. It also helps with changing things. I figure things out as I go along. I don't have a fully formed game that I can show to somebody and get them on board. I work very vaguely and with a lot of hope for a long time. That's very difficult to do with other people.

“If I work with somebody and they make a lot of progress and do a lot of cool stuff, it's hard for me to cut it and say: ‘Actually the game's not working the way we thought it would, so we have to change this stuff. We're also going to lose all five levels you made of the Mayan temple because there's going to be no Mayan temple.’ That's really hard for me to do.”

The singular results of Pope’s digital craft provide ample justification for his questing approach. He adds: “Games are perfect for me because they bring all the things that I love together in one place. Nothing else does that.”

Mars After Midnight is out now on Playdate.