In the past 10 years, Chicago’s inspector general has asked the Board of Ethics to find probable cause of an ethics violation only 13 times.

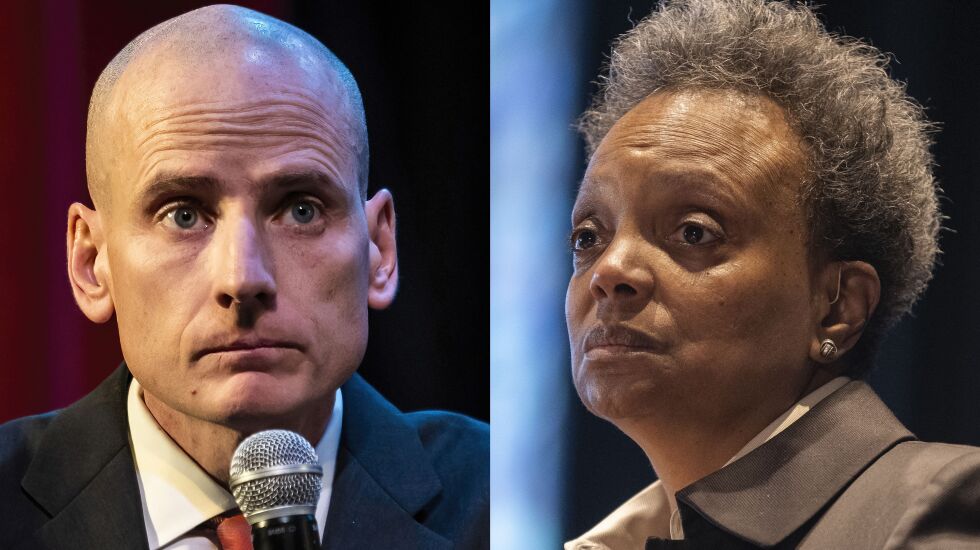

Three of those findings were in the last quarter alone. And the targets were former Mayor Lori Lightfoot, newly reelected Ald. Jim Gardiner (45th) and a member of the public who allegedly tried and failed to bribe a city inspector.

None of the three targets is identified in the quarterly report released Friday by Inspector General Deborah Witzburg. Her quarterly reports never name names.

But other sources and the underlying facts make it abundantly clear that the targets are Lightfoot and Gardiner. In both cases — and in the case involving an average Joe or Joan — the Board of Ethics has already agreed with the finding of probable cause.

That sets the stage for an adjudication process that, first, allows the accused to dispute the findings and, if the board disagrees, could culminate in the assessment of hefty fines. Fines range from $500 to $20,000 per offense or a fine equal to the financial benefit of the violation, whichever is greater.

Witzburg said the increased focus on ethics violations is “not an accident” or “aberration.”

She’s deliberately pursuing “more rigorous” enforcement to “pay down Chicago’s deficit of legitimacy.”

“We’re gonna hold people accountable when they break the rules, regardless of the positions they sit in,” she said.

Six weeks before the third-place finish that sealed her fate as a one-term mayor, Lightfoot publicly apologized for the attempt by her reelection campaign to recruit students at Chicago Public Schools and City Colleges in exchange for class credit.

She didn’t have much choice. The embarrassing story about the email sent by Lightfoot’s deputy campaign manager had already broken, undermining the reformer image that catapulted Lightfoot into office.

The Chicago Board of Ethics promptly asked Witzburg and her CPS counterpart to investigate Lightfoot’s reelection campaign.

A few weeks later, the other shoe dropped.

The Chicago Sun-Times and WBEZ-FM Radio reported that it wasn’t just one “bad mistake,” as Lightfoot had claimed. The Lightfoot campaign had sent more than 9,900 emails to CPS and City Colleges staff over a period of months.

The emails ranged from generic fundraising appeals to invitations to private town halls and requests for help gathering petitions, records showed.

Witzburg’s quarterly report includes even less detail.

It simply states that a “now-former elected official violated their fiduciary duty, misused city property and solicited political contributions from city employees in violation” of the ethics ordinance.

Emails sent by the Lightfoot campaign showed that she “misused” her “city title in pursuit of a political purpose as well as misused the authority” of her office “and city email addresses for political purposes,” the report states.

“The political campaign emails also demonstrated that the official improperly solicited political donations from city employees over whom the official had supervisory authority,” the report states.

The finding of probable cause against Gardiner stems from allegations that he “directed city employees to issue unfounded citations for weeds and rodents to the home of a constituent who had been publicly critical” of him.

“Elected officials do not get to wield the authority of the city in pursuit of their political agenda. And they don’t get to use city authority to punish political critics,” Witzburg said.

Two years ago, Lightfoot lashed out at Gardiner over profane, threatening and misogynistic text messages he sent to several people, including Lightfoot’s political consultant Joanna Klonsky and Anne Emerson, chief of staff to then-Finance Chairman Scott Waguespack (32nd).

One week later, Gardiner issued a rare public apology on the council floor for the embarrassment his messages caused.

He remains under federal investigation for allegedly retaliating against some Northwest Side constituents for political purposes.

The finding of probable cause against an everyday person is also important to Witzburg for the message it sends.

Never mind that the building inspector found multiple violations in the construction of two porches refused the bribe that the homeowner stuffed in his or her shirt pocket and reported it to authorities.

“The fact that people have the idea that you can buy off a building inspector — that’s the kind of thing that contributes to this deficit of legitimacy that we talk about,” Witzburg said.

“Just as we enforce the rule that city officials cannot take bribes [and] improper gifts, Chicagoans also have to get the message that … City Hall is not for sale.”

.jpg?w=600)