REACHING the point where the Fernleigh Track crosses Burwood Road at Kahibah, you are provided with a reminder of what makes this path in the midst of suburbia and our busy lives so special.

Scurrying along the road is a stream of vehicles, their occupants' eyes fixed on the bitumen and their daily schedules dead ahead. That's me usually, hurrying to wherever I have to get, missing the moment in pursuit of what is next.

But here I am, not on the road but on the track, and as a result my perspective is changed. Perched on my bike, watching the cars go up and down the road, I can take the time to slow down, to look around, to revel in the moment and the environment I'm pedalling through. Anyway, I have to wait for the crossing signal to turn green.

I could look ahead and see something wondrous, the Glenrock State Conservation Area. But I shall experience that once I cross the road. Instead, I look to the side of the track, and into the past.

ON THE FERNLEIGH TRACK

- "On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 1

- "On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 2

- "On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 3

- "On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 4

- "On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 5

- "On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 6

- "On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 7

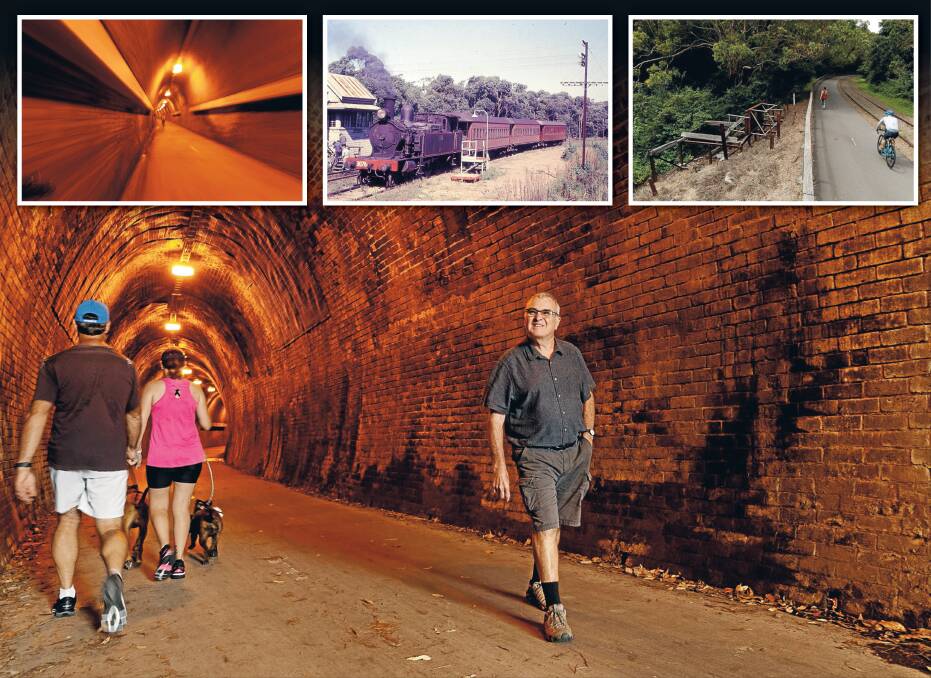

When this was a rail line, passenger trains stopped at a small station here. The Kahibah platform opened in 1907. The train was seen as a key to the growing residential areas up the hill.

As a Newcastle Morning Herald story in 1925 reported, "The train service has been considerably improved within recent years, and has brought the township within more frequent touch with the Newcastle district."

By 1939, however, the station had been downgraded. These days, at the site of the old platform, there is a replica "Kahibah" platform sign, but not much else. Not that there was very much at this station for a long time, going by the description given by local author Stephen White in his novel, How Bitter The Dust, which is set in a time straight after the Second World War.

The book's main character, David Maxwell, is an artist scarred by his war service and carrying a broken heart. He has left Sydney and is heading to a shack in the bush above Glenrock Lagoon, in the hope of finding some kind of peace. To reach the hut, David first has to catch a train - "the hissing engine, three submissive carriages in tow" - along the Belmont Line to the little station at Kahibah.

"To all appearances the railway station had been placed in the wilderness as a point for him to alight, and when he passed it would vanish," White wrote.

In real life, the train station, like the line itself, did vanish. But the setting no longer feels remote.

As soon as you pedal across Burwood Road and into the Glenrock State Conservation Area, a sense of wilderness returns.

Quite a few of the vehicles on Burwood Road have mountain bikes strapped to their backs, their owners keen to seek remoteness, and a shot of adrenaline, on the tracks around Glenrock.

Kate Harrison is a ranger with the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, which manages the state conservation area, so Glenrock is her patch. Kate says the Yuelarbah carpark, just off Burwood Road, is a popular entry point to both the track and Glenrock's trails for riders and walkers.

She reckons that the track and the park have complimented each other, with one raising the other's profile, particularly in these times of COVID restrictions, as visitor numbers have increased "dramatically".

"I do think it exposes people who may not have been aware of the conservation area or the track, so exploring one interests them to explore the other," Kate Harrison says.

Within the 550 hectares of the Glenrock State Conservation Area, there are 14 kilometres of mountain biking trails and another 20 kilometres of multi-use roads and tracks.

However, I stick to the Fernleigh Track, and to the bitumen. The track slides through a section of the western part of the conversation area. In terms of distance, it is not far, with only a kilometre or so before I reach the tunnel, but that short ride offers a variety of vegetation.

In the conservation area, you can find everything from the deliciously named Sydney peppermint and smooth-barked apple forests to rainforest remnants, where light trickles through the canopy and splotches onto the undergrowth near the track.

"It is remarkable to have this," says Kate Harrison, "to be exposed to such a mosaic of vegetation types in such a small area."

Little wonder the renowned Prussian explorer and naturalist Ludwig Leichhardt was rhapsodic in his description of the landscape, as he looked down the valley to Glenrock Lagoon, nestling beside the sea.

During his visit in 1842, Leichhardt noted the "most luxuriant vegetation" growing in the "Valley of the Palms".

In Glenrock, you journey back further than the 19th century, deep into time. For many generations, the Awabakal camped at the mouth of the lagoon, which they called Pillapay-kullitaran.

The Awabakal also had a quarry in the area, gaining materials for tools, and it is believed that part of the Yuelarbah track where walkers now tread was part of an important Aboriginal trading route.

Indigenous artefacts and sites have been found and identified, and Kate Harrison says more surveys are being done around Glenrock, "to understand how it was used, and to plan into the future".

"We're finding it's a rich canvas of both physical and spiritual significance," the ranger says.

Back on the track, just before the tunnel, is the Fernleigh Loop, an area littered with artefacts from a more recent time. They are rusting pieces of the rail days.

Lying on the ground is a signal post. However, it is now an arthritic arm, seized by the years, and no longer able to give directions. But once, it was used to signal to drivers if another train was approaching from the opposite direction along the single line, and they could go onto the loop to pass.

During a tour of Fernleigh Loop, Ed Tonks inspects the remaining section of tracks and says, "This was the main line". He points to the Fernleigh Track, following the curve of the old rail line, a few metres away and adds, "The loop was there".

There was another passing loop, on the other side of the main line.

Beside the track, tumbling into a gully, are the ruins of a signal box.

"In its heyday, this was operated 24/7," says Ed of the signal box, explaining that trains went up and down this line night and day.

Historical photos of the signal box depict a little weatherboard building, like something out of a bush fairy tale, squatting at Fernleigh Loop. It must have been a lonely existence for the staff.

These days, any feeling of isolation has all but disappeared, with houses having crept close to this part of the track.

Trains heading north would stop at Fernleigh Loop in readiness for the long and steep descent to Adamstown.

Ray Cross, a retired railway man who worked on the Belmont Line for 18 years, recalls what was required, when they had a line of wagons loaded with coal, in the days of steam engines.

"We'd come to Fernleigh Loop, stop the engine just before the tunnel, and the fireman would take up the slack on all the handbrakes, and the guard would do the same," he explains.

So it was Ray's job to help apply the brakes, to try to defy the forces of several hundred tonnes of coal and gravity pushing the train down the hill.

The tunnel was just around the bend from Fernleigh Loop.

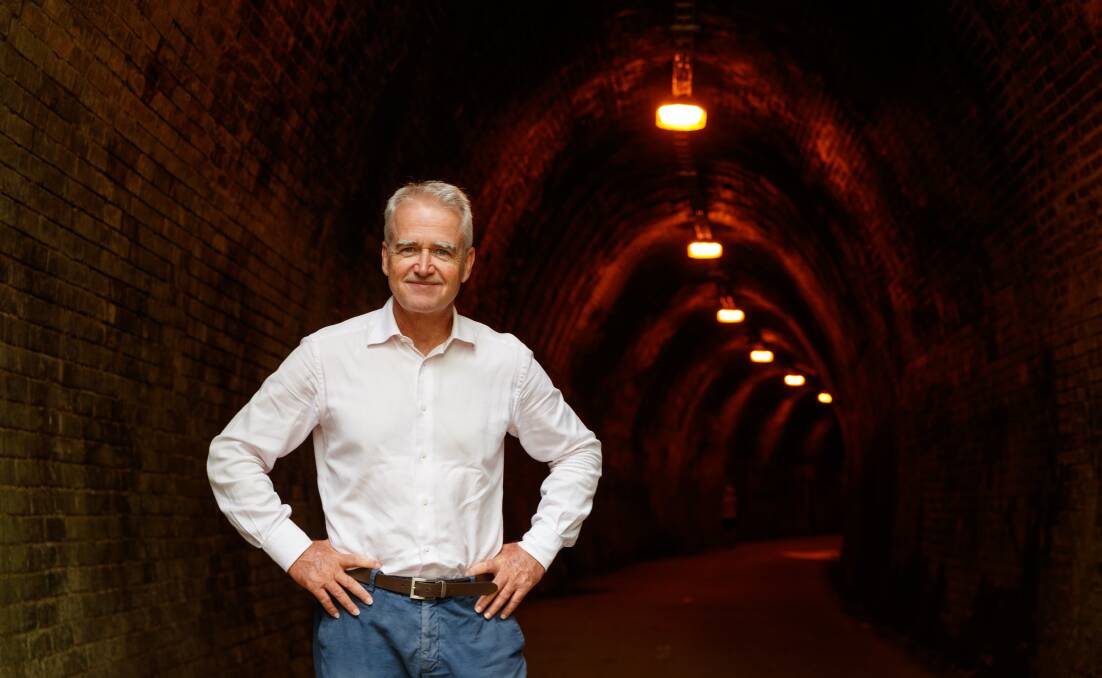

Most know it as the Fernleigh Tunnel, but its official name, Ed Tonks says, is the Redhead Tunnel, a reference to the mining company that had the rail line built in the late 1880s and 1890s to transport coal.

The tunnel was officially opened in 1892 and was seen as an engineering achievement.

"The tunnel through the ridge allowed for the transfer of the coal from the various collieries through to the port and to local markets," Ed Tonks says.

"So as a transport link it was vital, and it just so happened to look rather impressive."

The tunnel's southern entrance is more subtle than impressive, a hole in the landscape, burrowing under the Pacific Highway at Adamstown Heights.

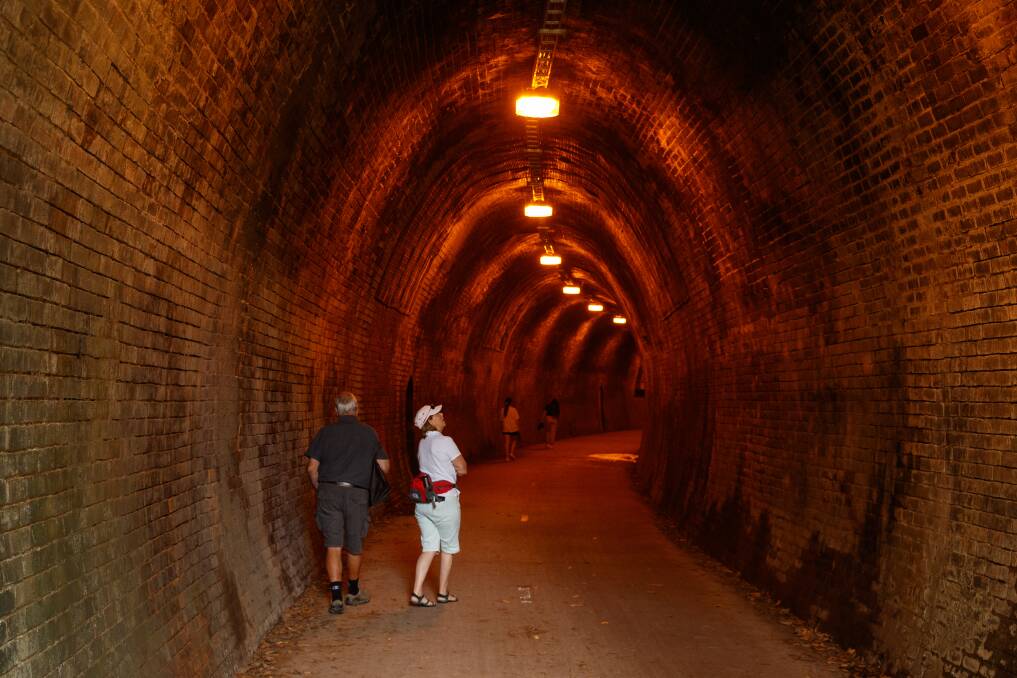

But then the hole reveals a string of lights through the 181-metre-long tunnel. The mandarin-coloured light gently illuminates the ellipsis of bricks curling over us.

A couple of kids ahead add a soundtrack to the atmosphere, making ghost sounds that bounce off the walls and die.

On the walk through the tunnel, Ed Tonks asks, "What don't you see?"

"The other end."

"Correct. You don't see light at the end of the tunnel.

"It's curved."

The historian explains the curve in the tunnel was to help slow the trains down as they negotiated the descending slope, and that design feature has only added to the heritage value of the tunnel 130 years later.

"This was transport technology from England at the time, transferred to the other side of the globe, when it was 'the world's best'," Ed Tonks says.

However, rolling slowly, with the handbrakes on, through the long, curved tunnel could be an uncomfortable experience for the steam train crews.

"Hot," replies Ray Cross, when asked what it was like in there. "Luckily I wasn't claustrophobic."

To deal with "the fumes, the smoke, and just about everything that came out", Ray and his workmates carried breathing apparatus kits, which he describes as being a metal mask and mouthpiece, with a hose that would connect to a compressed air outlet from the engine.

The air through that mouthpiece "tasted like oil", but it was better than breathing smoke and fumes.

"You couldn't see sometimes," Ray says. "And because of the sulphur coming out, all the polished handrails and operating wheels would have a yellow film by the time we came out, and you'd have to wipe them down."

These days a journey through Redhead Tunnel is breath-taking for different reasons. And it's an experience that is attracting tourists.

Deborah Goodman is from Sydney and, along with her two daughters, she is visiting the Fernleigh Track for the first time.

"We only found it by luck, when we were Googling the area," Deborah Goodman explains.

As she enters the tunnel, Mrs Goodman exclaims, "Wow! Good grief!"

She hoots, delighting in the echo, before saying, "It's great. I love it".

"I cannot believe a train got through this!," Deborah Goodman says. "This is fabulous! Great use of a railway track."

In turn, the rail historian delights in the Sydney visitor's reaction to the tunnel, which was integral to the operation of the line for a century.

"So this is so significant because it enabled that functioning," Ed Tonks says as he gazes up at the brickwork. "It has intrinsic historical value in itself, and also it's one of the few instances where people can appreciate the interior of a tunnel legally and safely."

After a few minutes' walking, I can see the light at the end of the tunnel.

And that means our Fernleigh Track journey is also nearing its end.

Tomorrow: "On The Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan" concludes, with the final leg to Adamstown.

Read more:

"On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 1

"On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 2

"On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 3

"On The Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 4

"On The Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 5