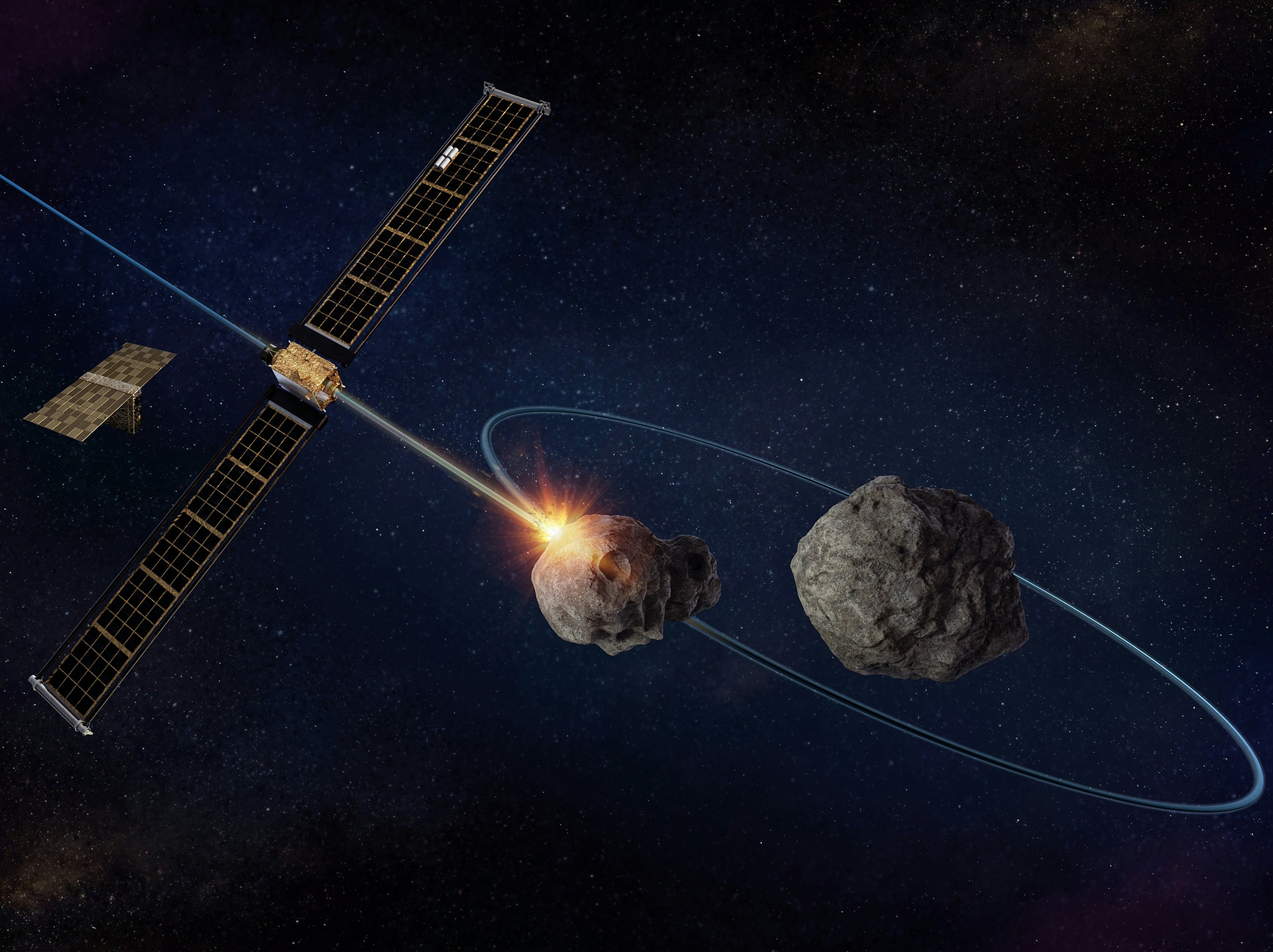

The epic collision of NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), which took place on September 26, 2022, was the space agency’s first major experiment at managing the existential threat of a near-Earth asteroid. The experiment sought to learn if we could knock one off course.

Early results were positive. DART precisely struck Dimorphos, the moonlet of the larger near-Earth asteroid Didymos located 6.8 million miles away from the planet. It’s an achievement NASA Administrator Bill Nelson described as a “watershed moment for humanity.” More good news poured in weeks later, when NASA confirmed the crash altered Dimorphos’ orbit around Didymos.

On Thursday, Hubble Space Telescope officials revealed new findings: It’s likely that DART also released 37 boulders into space.

Why do these boulders matter?

Just having seen these boulders is a special feat. According to a statement published Thursday by the European Space Agency (ESA), “the boulders are some of the faintest objects ever imaged in the Solar System.” ESA manages Hubble alongside NASA.

The boulders, which range in size from 3 feet to 22 feet across, are a critical part of the DART story. The mission’s goal is to push, not obliterate, an asteroid. Blowing one up is too risky, potentially scattering numerous rocks onto many new trajectories. The designers of the planetary defense mission sought an approach that’s more like a powerful nudge than an explosion. Nuance is the goal, so NASA is seeking all the details it can gather about how the kinetic impact played out.

Prior to their ejection into space, the boulders were likely sitting on the surface of Dimorphos, according to ESA officials.

These boulders are most likely harmless. According to the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Maryland, which leads the DART investigation team for NASA, rocks roughly 13-feet wide — roughly the median size of the Dimorphos boulders — may light up when they enter Earth’s atmosphere, but they tend to have little to no effect on the ground.

But Hubble’s revelation will probably play an important role in the development of future planetary defense missions. Many asteroids are boulders gathered together into giant clumps. Space agencies will therefore need to investigate what happens if kinetic impactors dislodge rocks into space.

The next steps of planetary defense

ESA’s Hera mission will launch in 2024 to learn more and will do a post-impact survey of Dimorphos.

Before Hera’s close approach, data from spacecraft like Hubble, the James Webb Space Telescope and DART’s European companion LICIACube (short for Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging of Asteroids) are revealing the quantity and quality of the ejecta that went flying.

DART is designed to help prevent a really bad day from happening. But rest assured that the majority of asteroids in space are harmless. According to APL, “Very few of the billions of asteroids and comets orbiting our Sun are potentially hazardous to Earth, and, for at least the next century, no known asteroid threatens our planet.”