Roger Angell, a famed baseball writer and reigning man of letters who during an unfaltering 70-plus years helped define The New Yorker’s urbane wit and style through his essays, humor pieces and editing, has died. He was 101.

The New Yorker announced his death on Friday. Other details were not immediately available.

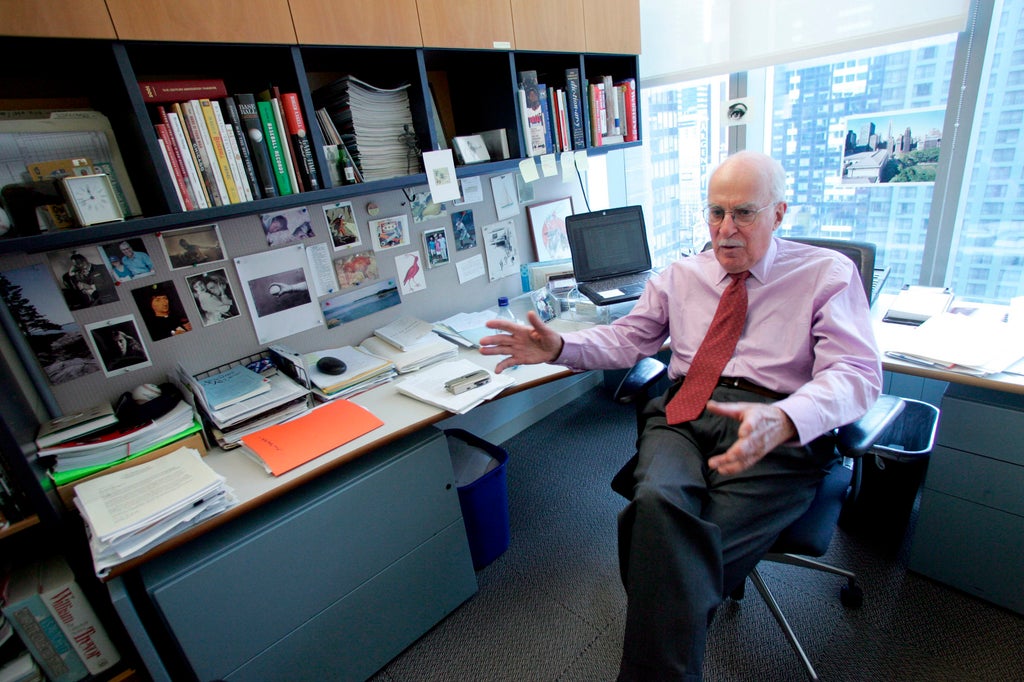

Heir to and upholder of The New Yorker’s earliest days, Angell was the son of founding fiction editor Katharine White and stepson of longtime staff writer E.B. White. He was first published in the magazine in his 20s, during World War II, and was still contributing in his 90s, an improbably trim and youthful man who enjoyed tennis and vodka martinis and regarded his life as “sheltered by privilege and engrossing work, and shot through with good luck.”

Angell well lived up to the standards of his famous family. He was a past winner of the BBWAA Career Excellence Award, formerly the J. G. Taylor Spink Award, for meritorious contributions to baseball writing, an honor previously given to Red Smith, Ring Lardner and Damon Runyon among others. He was the first winner of the prize who was not a member of the organization that votes for it, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.

His editing alone was a lifetime achievement. Starting in the 1950s, when he inherited his mother’s job (and office), writers he worked with included John Updike, Ann Beattie, Donald Barthelme and Bobbie Ann Mason, some of whom endured numerous rejections before entering the special club of New Yorker authors. Angell himself acknowledged, unhappily, that even his work didn’t always make the cut.

“Unlike his colleagues, he is intensely competitive,” Brendan Gill wrote of Angell in “Here at the New Yorker,” a 1975 memoir. “Any challenge, mental or physical, exhilarates him.”

Angell’s New Yorker writings were compiled in several baseball books and in such publications as “The Stone Arbor and Other Stories” and “A Day in the Life of Roger Angell,” a collection of his humor pieces. He also edited “Nothing But You: Love Stories From The New Yorker” and for years wrote an annual Christmas poem for the magazine. At age 93, he completed one of his most highly praised essays, the deeply personal “This Old Man,” winner of a National Magazine Award.

“I’ve endured a few knocks but missed worse,” he wrote. “The pains and insults are bearable. My conversation may be full of holes and pauses, but I’ve learned to dispatch a private Apache scout ahead into the next sentence, the one coming up, to see if there are any vacant names or verbs in the landscape up there. If he sends back a warning, I’ll pause meaningfully, duh, until something else comes to mind.”