Writing from the United States, where Omicron has pushed Covid-19 hospitalisations to record levels, Marc Daalder reports on what New Zealand needs to do to prepare for the variant

Analysis: The terrifyingly rapid spread of the Omicron variant has upended much of the common wisdom overseas about how to respond to the pandemic. When it arrives in New Zealand, it will have a similar effect.

From the United States – where more people are in hospital with Covid-19 than at any previous point in the pandemic – to Australia, where experts have estimated as many as 200,000 people were infected each day in early January, Omicron has proven extremely difficult to control with familiar methods.

If New Zealand wants to fare better than the rest of the world, we too will need to do things differently – and to plan for how to do so before the variant arrives.

"I think it's likely that we'll need something stronger than the red level of the traffic light system. The traffic light system was designed for Delta," University of Canterbury mathematics professor and Te Pūnaha Matatini disease modeller Michael Plank told Newsroom.

In fact, a lot of our planned response to Omicron was designed for Delta. The Prime Minister said on Thursday that the Government's hospital capacity and health workforce planning didn't need to be revised in light of Omicron, because it had been prepped for a Delta outbreak.

International experience has shown that the strategies that worked for Delta don't work as well for Omicron. And we are fast running out of time to come up with a new plan before Omicron takes off in the community.

The field of play

There are three crucial things to understand about the state of play once Omicron arrives in New Zealand and starts to seriously spread.

First, while a small outbreak of a handful of cases – like the border-related incursion in Auckland – could theoretically be contained and eliminated, once community transmission begins in earnest, we will not be able to control this variant like we did Delta and the original wild-type coronavirus.

"When we get a community case of Omicron, there may be a short window at the start where it is feasible to stamp it out with really good contact tracing and a bit of good luck," Plank said. "We might be able to stamp out a small outbreak and then buy ourselves a bit more time. But once it's established, I think suppressing it and keeping it at a low level will become much harder."

Amanda Kvalsvig, an epidemiologist at the University of Otago, agreed that current settings won't allow us to suppress or eliminate Omicron. Given there was no public appetite for lockdowns – and given Jacinda Ardern on Thursday ruled out a strategy reliant on lockdowns – then none of the measures in the toolbox would be sufficient, she said.

"We can expect contact tracing to fall over fairly quickly." – Amanda Kvalsvig

Plank said it was possible we could try to suppress the virus like Singapore is attempting. There, people are not allowed to gather in groups of more than five people, in an effort to cut off chains of transmission and avoid super-spreading.

"I'm not sure what the exit plan with that would be and whether that's really sustainable without long-term lockdowns, which obviously everyone is desperate to avoid," he said.

Due to Omicron's much greater ability to infect vaccinated people (even if they are still generally protected from severe disease and death), the traffic light system's heavy reliance on vaccine passes will be much less effective at slowing the virus. It is also at least as inherently transmissible as Delta and has a shorter incubation period – the time between a person becoming infected and then becoming symptomatic and infectious – so it spreads faster.

"Contact tracing will no longer be able to keep up and contribute very much, formally," University of Otago epidemiologist Michael Baker told Newsroom.

"We can expect contact tracing to fall over fairly quickly," Kvalsvig agreed, "given the typical steeply exponential epidemic curve and large number of cases, so the focus should be on those public health and social measures that prevent spread between people, whether or not they know they’re infected."

Instead of stamping it out, our best bet will be to slow the virus down.

That brings us to the second crucial fact about life with Omicron: Even if we slow it down, far more people will be infected than in any previous phase of the pandemic.

Those people will need to isolate for at least a few days if we want to continue slowing the spread of the virus. We must expect workforce shortages across the economy, but especially in frontline roles that can’t be done from home: healthcare workers, supermarket workers, truck drivers and other parts of the supply chain will all be affected.

Plus, on an individual level, each New Zealander's chance of being infected with Covid-19 will be markedly higher once Omicron arrives.

We’re entering this phase of the pandemic (like all the previous ones) with much less health system capacity than other countries.

The third and final point about Omicron? It could still threaten the health system even if a smaller percentage of cases requires hospital-level care.

On the one hand, this is simple maths. If Omicron leads to 20 to 40 times more cases than previous variants, then it would have to be 20 to 40 times less severe to have no greater impact on the health system. While it is less severe, it isn't that much less severe.

Stuff has reported previously on why we shouldn't see the hospital burden in New South Wales as a forecast for what will happen in New Zealand – namely, that Omicron's arrival across the ditch coincided with a rise in Delta cases and that many of those who ended up in hospital had Delta, not Omicron. But there's another reason we shouldn't take our hints from overseas: Our health system capacity is much, much lower than that of our peers.

Across the country on Thursday, 68.3 percent of ICU beds were occupied and 84.7 percent of general ward or hospital beds were full. That's in summer and with almost no Covid-19 in the community.

Some of this capacity can be freed by delaying elective operations and it could also be expanded with surge capacity, but we’re entering this phase of the pandemic (like all the previous ones) with much less health system capacity than other countries. That will only be exacerbated by the likely shortages of healthcare workers described above. These shortages will be much more significant than what we might have faced with a large Delta outbreak, due to Omicron's increased ability to infect the vaccinated.

"This risk is why we need maximal effort to control Omicron, as health system capacity is a critical need for a functioning society. Very few New Zealanders (or indeed anyone from a high-income country) will have experienced an acutely overwhelmed health system. Suffice to say, we need to avoid this outcome at all costs," Kvalsvig said.

The strategy

In light of these three crucial factors – that Omicron can't be controlled, only slowed; that many people will be infected; and that our health system requires very little prodding to collapse completely – New Zealand must commit to a new strategy of mitigating spread of the virus to protect the health system once Omicron arrives.

This will require clear explanation from the Prime Minister on down – the sort of crisp communications that accompanied the announcement of the alert level system in March 2020 and decidedly not the muddled confusion when Ardern abandoned elimination and unveiled the three step system for Auckland's exit from lockdown in October.

The Government will have to set new expectations for the level of Covid-19 New Zealanders should plan to see. It will have to issue clear rules about what to do if you're a case and what to do if you're a contact, because there are likely to be many more of these than can be contacted one-on-one.

Most importantly, Ardern will have to leave the door open to further changes to the strategy – to further restrictions, in reality – if the health system is threatened.

"It’s important to clarify that a mitigation strategy for Omicron will almost certainly need more organised effort and resources than the elimination strategy has needed for previous variants, so this change in strategy will not in any way be a step down," Kvalsvig said. Mitigation doesn't mean "letting it rip".

"We’re going to have to throw absolutely everything we have at this challenging variant. But we should also remember that several countries that experienced explosive spread of Omicron weren’t making full use of existing Covid-19 control measures and were prioritising business interests rather than population health. We have a very experienced pandemic response with generally good infrastructure and if we tighten up some obvious gaps we may do much better than other places."

Another term for mitigation is flattening the curve. It is pretty much inevitable that a large number of New Zealanders will get Omicron. The goal here is to smooth that out over many weeks or months, so that the peak of the epidemic doesn't send more people to hospital than the hospitals can treat.

In order to effectively implement a mitigation strategy, we'll need a lot more detailed data about the state and capacity of the health system. DHBs may well report this information to the Ministry of Health, but making it public will be just as important as previous types of data, like that concerning Covid-19 cases or the vaccine rollout.

Ideally, information about the ICU and general ward capacity in each DHB would be available, as well as the degree to which beds are filled by Covid-19 patients or those without Covid-19.

When Omicron spreads widely, some people will turn up to hospitals with unrelated issues and test positive for the virus. Elsewhere, these cases are considered "incidental" Covid-19. The Government will need reporting systems that distinguish between these cases to get a better picture of the real impact Covid-19 is having on the health system.

If health officials believe people should be engaging in a particular behaviour because there is a public health benefit, then the Government should tell people to do it, not merely “encourage” it.

However, it's important to emphasise that not everyone who tests positive for Covid-19 after arriving at the hospital is an "incidental" case. Covid-19 is a respiratory illness, but it can also affect the heart, kidneys, nervous system and other organs. Someone who turns up to hospital with a severe asthma attack or a heart issue, and who then tests positive, may still only be in hospital because of their infection. Data will need to reflect this ambiguity.

Moreover, either way, Covid-19 cases place additional pressure on hospitals. Even the person with a broken leg who tests positive for the virus will still need to be isolated from other patients and treated with additional PPE to avoid spreading the virus to staff or patients. That takes more time and resource and reduces the care available to others.

It will be tempting as Omicron spreads for the Government to devolve responsibility for the response to individuals. We have seen this overseas at various stages of the pandemic. Want an N95 mask in the United States? Go find one yourself. Need a rapid test in Australia? Fork up $70 to scalpers or go without.

One of the key strengths of New Zealand's response to the pandemic thus far has been the recognition that in times of emergency like these, it is the Government's duty to step up and play a greater role in protecting the public. Where other countries have issued health recommendations but allowed individuals to decide their own comfort with risk, Ardern has rightly seen that each individual decision in a pandemic has an impact on public wellbeing and made rules rather than recommendations.

If health officials believe people should be engaging in a particular behaviour because there is a public health benefit, then the Government should tell people to do it, not merely “encourage” it. Some of the weakest parts of the response (like the low uptake of digital contact tracing or masks) have come when the Government abdicates this role.

In the Omicron wave, other countries have gone further down the path of leaving it up to individuals. If we want different and better results than those seen elsewhere, we should stick to what worked for New Zealand.

Fortunately, Ardern has already signalled that this approach will be maintained by saying that rapid tests will be free for all New Zealanders.

"A key principle is that if the [Government] is asking for action from individuals (like mask wearing), this action still needs to be supported by Government to be effective and equitable," Kvalsvig said. That could include importing high-grade masks, mask mandates and "ensuring affordable or even free masks for everyone". "Only if those structural-level supports are in place will the individual-level action be effective and fair."

How to slow the virus

There are four crucial measures that could slow Omicron while allowing New Zealanders to maintain some semblance of a normal life.

The first is a massive push on booster shots. The evidence is clear: Two shots does a good job of protecting you from severe illness or death with Omicron, but is much less effective at stopping you from getting infected in the first place. A third shot restores that protection against symptomatic infection to 80 percent. The more people are boosted, the less easily Omicron can transmit through the community.

We're boosting rapidly, but there's plenty of room for improvement. Right now, there are more than 800,000 New Zealanders who are eligible for a booster but who haven't yet had one. That number needs to fall rapidly – through incentives or a Vaxathon or whatever else can be shown to work.

With more than 2.5 million doses in storage, supply is not an issue. We also have significant workforce capacity to roll out vaccines at the moment – although that will reduce when Omicron arrives and spreads to the health workforce.

"I think it's going to be really crucial to get our older age groups boosted because they're at the highest risk of needing hospital treatment and they also tend to be the people who were vaccinated longest ago, so immunity will have started to wane by now. So I think that's that's probably the most important thing," Plank said.

Kvalsvig agreed and added that the Government should both shorten the gap between paediatric vaccine doses – in the United States, it's just three weeks – and allow those aged 12 and over to be boosted.

Given the current pace of boosters and the degree to which Omicron can evade immunity from just two shots, New Zealand's collective immunity is actually declining each day. The number of people with waning immunity is far higher than those getting boosted or getting vaccinated for the first time. We're in a war of attrition against the waning effect – and right now, we're losing.

"It will be important to make child-sized N95 masks freely available." – Amanda Kvalsvig

The second measure to slow the spread of the virus is an updated approach to masks.

"There is increasing international advice that people should shift to using higher quality N95 respirator style masks routinely when indoors with other people during an Omicron outbreak," Baker, Kvalsvig and three colleagues wrote in a recent blog post.

The Government should clearly communicate the need to use N95s, particularly in high-risk venues, and ensure that adequate supply of these is cheaply or freely available.

Kvalsvig told Newsroom that this would be "a highly cost-effective and equitable approach that could have significant benefits in an Omicron outbreak".

"It’s still speculative, but some researchers have suggested that the increased upper airways involvement of the Omicron variant means that masks may offer even more protection than with previous variants.

"It will be important to make child-sized N95 masks freely available also. As well as being more effective than cloth or surgical masks, many children find them more comfortable."

In some ways, masks are an even more variant-proof measure to adopt than vaccinations. After all, masks don't wane in effectiveness over time.

"Masks are arguably more effective at stopping someone from transmitting Omicron than being double vaccinated with Pfizer vaccine. But there has not been the same emphasis," Baker said.

"As well as protecting the person's who's vaccinated, vaccines dampen down transmission risk. Masks are very analogous to vaccines – if everyone's wearing masks, it protects them but also dampens down transmission."

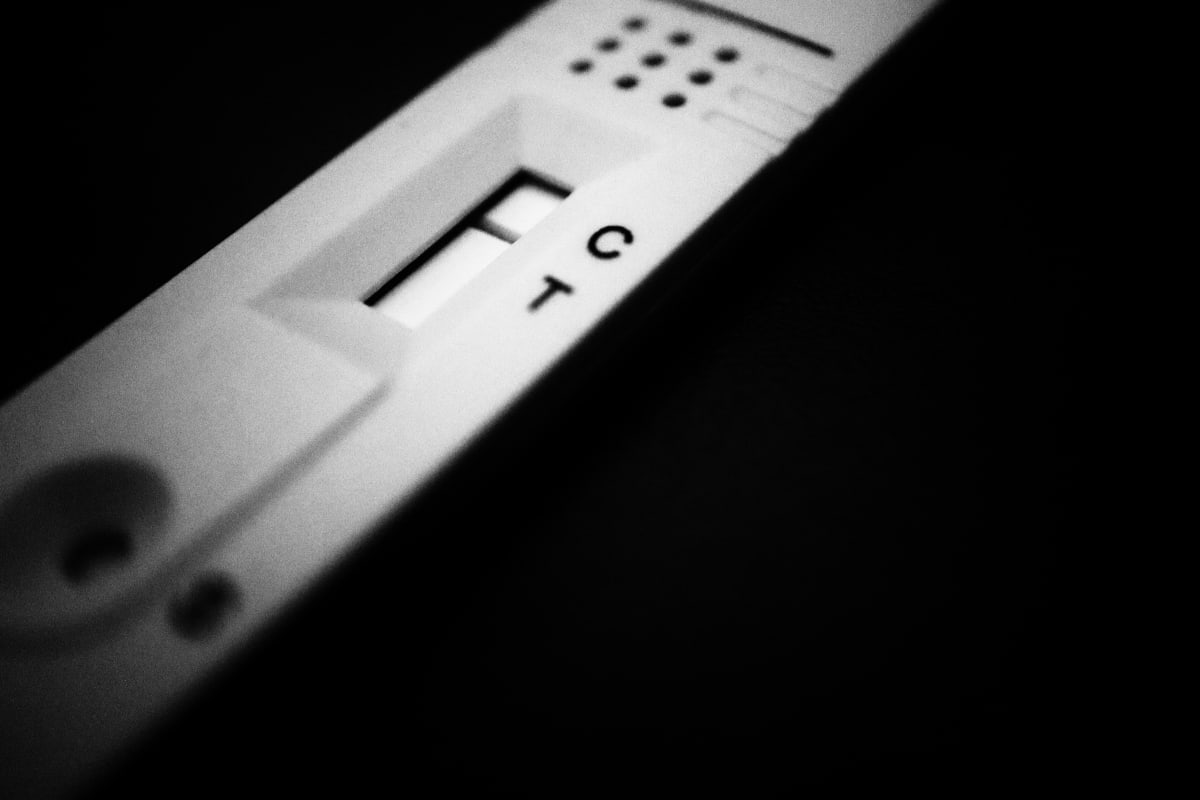

The third measure is a massive expansion in the use of rapid antigen tests (RATs) in responding to Omicron. These at-home tests will provide a range of important functions.

Most significantly, they will supplement the usual PCR testing capacity when demand gets too high. Ardern says we can run 40,000 tests a day while the Institute of Medical Laboratory Science's president Terry Taylor told RNZ the figure would be 60,000 by the start of February. That latter stat, at least, is based on pooling multiple test samples together and running them at the same time. This is only efficient when there are few positive cases in the community – any batch that has a positive result needs to be individually re-processed.

Either way, New South Wales labs have had to run 100,000 PCR tests on some days – a number that would "inundate" New Zealand labs, Taylor said.

Rapid tests are likely to be needed once PCR lab capacity dries up. That means the Government will also need processes for uploading at-home test results to national contact tracing and case management databases. It will also need to have enough rapid tests on hand and a way of getting them to people, even as supply chains buckle due to labour shortages.

There are at least two other potential uses for rapid tests, assuming there are enough of them around. People could use RATs to test themselves before going to large social events or visiting high-risk people – likely unvaccinated children or the elderly. That could be done voluntarily or enforced with a mandate for the highest-risk situations (visiting an aged care home or going to a nightclub, for example).

The other use is related to the fourth measure needed to tackle Omicron: Updated isolation rules.

Currently, Covid-19 cases need to isolate for at least 10 days, including three symptom-free days at the end. Their household contacts must then isolate for an additional 10 days after the case's isolation period ends. If Omicron infects thousands or tens of thousands of people every day, these rules could bring the country to an abrupt halt.

A shorter isolation time is worth looking at, Baker and Kvalsvig said. Better financial support for those in isolation will also be needed to ensure they don't break the rules out of a need to pay the rent.

"If access to tests become difficult, it will be even more important to have sick-leave provision and other supports in place so that people can stay at home if unwell, whether or not they have a definite diagnosis," Kvalsvig added.

Rapid tests could play an important role in a new isolation scheme. Because they tend to return a positive result only when someone is infectious (while PCR tests can come back positive if the person is not yet infectious or even no longer infectious), a negative antigen result could be used to clear people from isolation after a shorter time period than the current 10-to-14 days.

It's clear that none of these four measures will be enough on their own. Quite possibly, Baker said, even all four of them might not slow Omicron. But they offer a starting point for how to implement a new mitigation strategy for the virus – keeping the health system afloat while not completely shutting down everyday life.

Even under all of that, however, Baker says we need to keep all of our options open.

"Several hundred deaths would occur in New Zealand if the virus gets loose shortly and transmits widely," he said.

"People say, 'We can't have a lockdown again'. But actually, if you have very widespread infection, it has the same effect on the economy, and everything, of really causing a lot of harm. It's going to be disruptive for schools and all institutions. It's a pattern seen overseas and I don't think it will be different here.

"As soon as I comment on this, people say, 'We can't think of having anything like a Level 3 lockdown again'. Well, actually, the virus will do that for you."