“Sometimes, I forget what I was doing, and have to pause and think.”

“After having COVID-19, I have not been able to go to work due to breathing difficulty.”

“I feel so tired, with aches and pains in my muscles and joints.”

These are complaints voiced by some people long after recovering from COVID-19. While it is not unusual for a viral fever to leave a person feeling tired for a few days, people with long COVID experience symptoms for several months or even longer.

Several symptoms

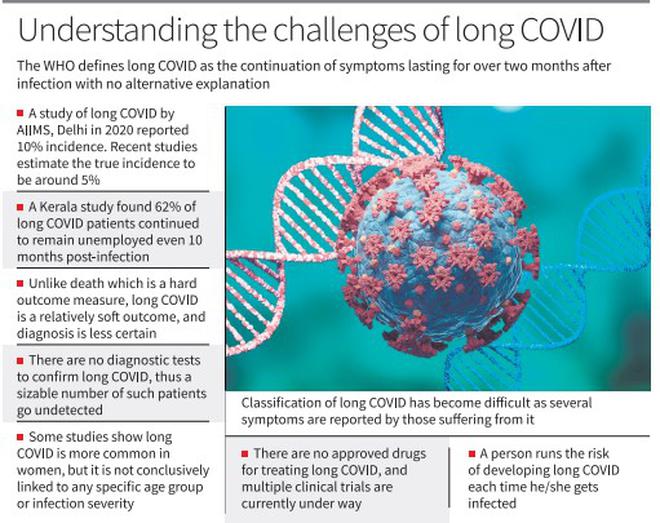

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines long COVID as the continuation or development of new symptoms (beyond three months after the initial infection) lasting for over two months with no alternative explanation. Studies have attempted to determine how commonly it occurs. However, since there are several symptoms reported by those who suffer from long COVID, classification has become difficult. For instance, a study that uses tiredness as a criterion could overestimate the prevalence, as that symptom is already common among the general population.

A study of long COVID from AIIMS, Delhi during the first wave reported its incidence to be as high as 10%. More recent studies estimate the true incidence to be around 5%, which implies that one out of 20 patients with COVID-19 go on to develop long COVID. While gradual recovery has occurred in some cases, this has not been the case for others. For instance, a paper from Kerala reports that 62% of long COVID patients who became unemployed following their initial illness remained so even at 10 months post-infection.

Across the world, millions continue to suffer from long COVID, and a study last year by the Atlanta-based CDC found that nearly one-fifth of people in the U.S. who had the disease in the last two years continued to suffer from long COVID.

The impact of any disease is assessed based on certain outcomes. For instance, in the case of polio, the number of people who died or suffered paralysis after initial infection are commonly used as hard outcome measures, as they are binary in nature and relatively easy to measure. Similarly, For COVID-19, death is a frequently discussed hard outcome measure. However, long COVID is a relatively soft outcome because its onset is more insidious and its diagnosis is less certain. Many people experiencing long COVID do not rush to the doctor, and among those who do, a diagnosis is seldom made. Frequently, such people are ignored as ‘psychological’ or ‘anxiety-related’. Unfortunately, there are no diagnostic tests such as X-rays, CT scans, or blood tests to confirm long COVID. Therefore, a sizeable number of patients with long COVID go undetected and either suffer in silence or end up being victims of those who peddle miracle cures on social media.

Research is ongoing to determine why only some individuals develop long COVID. Some studies have found that it is more common in women, but it has not been conclusively linked to any specific age group or the severity of the initial infection. Initially, long COVID was thought to be an autoimmune phenomenon, and some believe it is due to persistence of the virus in remote parts of the body, such as the gut. Reactivation of other viruses in the body is also implicated. There is evidence of an abnormal immune response in long COVID, but it is not clear what drives this response or what can be done to alleviate it.

At present, there are no approved drugs for treating long COVID, and multiple clinical trials are currently under way. While vaccination has been successful in minimising severe cases of COVID-19 and death, it has not been shown to prevent long COVID. The WHO said the best way to prevent long COVID is to avoid getting infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 disease.

Preventing COVID-19 on a forward timeline is challenging for many reasons. Firstly, many infections occur without symptoms. Second, the virus is constantly evolving to escape human immune responses arising from vaccination and/or prior infection. This means that repeated bouts of COVID-19 can be expected, especially when precautions are not followed during a regional surge. A recent study published by the CDC found that 15% of reinfections occurred as early as two months after initial infection. Every (re)infection has a possibility of causing long COVID.

Pandemic fatigue

The recent declaration by the WHO ending the COVID-19 public health emergency of international concern is misunderstood as the end of the pandemic itself. Blame it on pandemic fatigue, despite the WHO’s assertion that COVID-19 continues to be an “established and ongoing health issue”, people end up taking home a different message. For them, the declaration of the end of the public health emergency is tantamount to the pandemic coming to an end. This misconception could worsen the spread of the virus in the future.

Recognising the existence of long COVID and continuing to implement regionally appropriate mitigation measures when the situation so demands will help in reducing the negative impact of the pandemic on global health and productivity.

( Rajeev Jayadevan is co-Chairman, National IMA COVID Task Force)