Having highlighted the failures and fragility of a globalized food system, the COVID-19 pandemic created a sudden infatuation with local consumption, which was widely encouraged by the Québec government as a measure to mitigate the effects of the pandemic.

On one hand, delays in the arrival of foreign workers and the disruption of slaughterhouse operations were among the greatest difficulties faced by Québec farmers. On the other hand, one of the biggest challenges for smaller-scale local ecological producers was to promptly satisfy an overwhelming demand for fresh, local food.

However, this is not a trend that has lasted: while there was a sharp return to normal in 2021 (compared to 2020), some local farmers even reported a drop in demand for their products in 2022.

Nevertheless, the Québec government has been redoubling its efforts to promote local food in the name of “food autonomy,” whether by increasing its support for Aliments du Québec (the organization responsible for branding food produced within the province), or by adopting its Stratégie nationale d’achats d’aliments québécois (a strategy for local food procurement within public institutions). The province is also investing heavily, albeit narrowly, in technologies such as greenhouses and food processing infrastructure.

So how does one explain the decline in the popularity of local, ecologically grown food?

As researchers in sustainable food systems, we would like to offer some considerations as to why politicians and citizens should be targeting changes that are far more ambitious than short-lived support for local food production and consumption.

Food autonomy is insufficient

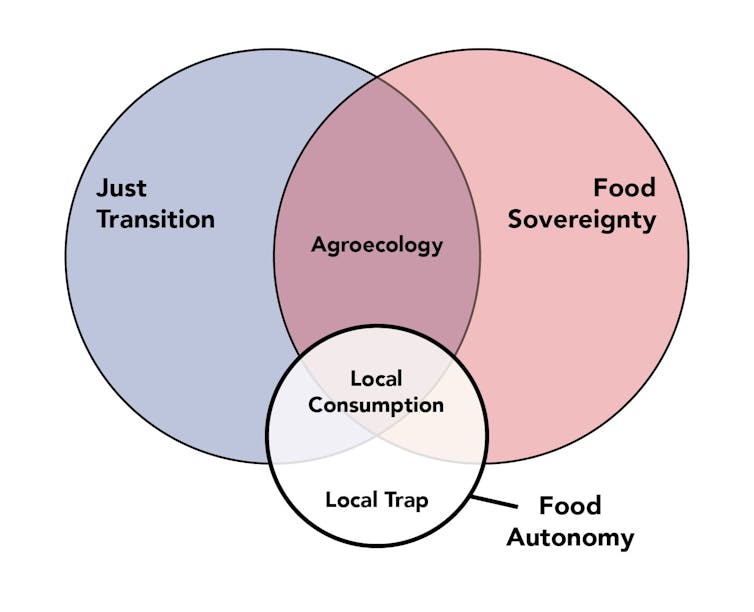

The main conclusion that we have drawn from the research we conducted with local farmers and others involved in alternative food initiatives is that “food autonomy,” as a framework for reorganizing the food system of Québec (and other provinces), is not enough. Instead, what is needed is a “just transition”.

How is food autonomy insufficient? First of all, it does not adequately challenge dominant production models. Those of smaller-scale ecological producers, which can be very diverse in terms of on-farm practices, should be both prioritized and replicated.

In the face of climate change in particular, the farmers we interviewed believe that greater biodiversity on smaller scales promotes the resilience of agricultural ecosystems. Conversely, conventional models, often “hyper-specialized” and dependent on a large quantity and variety of off-farm inputs, do not allow for such resilience.

The precarity of farming

However, regardless of the model of production, another blind spot of food autonomy is the considerable and ongoing precariousness experienced by the people growing our food. Our research confirmed what has been demonstrated in recent years: that the financial and mental burden that farmers are facing is worrisome and unsustainable.

Contributing to this burden is the well-known shortage of domestic agricultural labourers, which is being compensated for by migrant workers whose living and working conditions are too often deplorable.

In addition, smaller-scale farmers in particular must very often wear the hat of both food producers and marketing and distribution experts, while they receive very little support in either of these areas. The marketing and distribution side is particularly difficult for local ecological products.

While smaller-scale farmers cannot meet the supply chain requirements of conventional supermarkets, such as a stable supply throughout the year or a long shelf life, direct marketing through farmers’ markets or Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) subscriptions, for example, can be both time-consuming and relatively inefficient.

Moreover, the logistical and economic accessibility of these types of marketing is compromised by socio-economic factors that go well beyond the scope of food production; small-scale ecological growing is often incompatible with the fight against food insecurity. Connections between marginalized consumers and ecological farmers are therefore difficult and only occasionally realized through targeted initiatives.

In sum, it is clear that food autonomy does not address all of these issues, which is why researchers refer to it as the “local trap” when it is promoted as a framework for action on its own. Local consumption alone does not address the majority of the more substantial problems that lie at the heart of our food system.

Towards a just transition

The objective should not be simply to achieve food autonomy, but to undertake the process of a just transition towards a socially just and agroecological food system. This is an opportunity to actively rethink the current food model, which is currently designed to prevent such a transformation.

It is important to note that this process must be structured in such a way that all agri-food stakeholders move towards a common goal: environmentally friendly localized agriculture that produces healthy, accessible, and inclusive food without compromise. In other words, a just transition is about inviting everyone to the table, from farmers to consumers, to think beyond established models and popular practices.

To date, our research suggests that the development of an “infrastructure of the middle” would provide an effective physical and logistical structure for both smaller-scale farmers and consumers. Briefly, such infrastructure, both tangible and intangible (e.g., networks and resources) would allow for a sufficient mass of ecological farmers and other food producers and processors, on one hand, and consumers, on the other, to overcome the difficulties of direct marketing as well as those associated with conventional supply chains.

More specifically, the infrastructure of the middle would be adapted to local realities and can take the form of, for example, food hubs, community-based abattoirs, or cooperative food markets.

A question of collective responsibility

Of course, it is possible to name such examples because they already exist. However, the current forms of product aggregation and co-operation between farms, organizations and consumers are marginal and need to be further supported. Our research has shown that such examples of infrastructure of the middle require a significantly increased contribution from outside the agricultural community.

Currently, most alternative and collaborative marketing initiatives are carried out by third parties, often community-based food insecurity organizations, and representatives from such organizations agree on an important fact: the development of an infrastructure of the middle requires substantial government support as well as deep public engagement. In other words, the establishment of new infrastructure and new initiatives in general must be taken up as part of the transition toward a more just and ecological food system.

Finally, the just transition as an action framework requires us to no longer ignore the blind spots of food autonomy that include the climate crisis, community well-being, and social justice. Indeed, to engage with our food system is to realize that food is at the heart of our social fabric.

As homesteader, activist, and author Dominic Lamontagne told us, “Since everyone benefits from the act of eating, everyone should be pitching in.”

We all need a healthy and just food system. We all need to get involved in one way or another to shape not only the food system of the future, but healthy, resilient communities in which we will feel proud to be living.

In fact, bringing about such changes is our collective responsibility.

Bryan Dale received financial support from Bishop's University to pursue his research.

Marianne Granger received financial support from Bishop's University in contributing to this research project.

Mélodie Anderson received funding from Bishop's University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.