When a series of women started accusing married Maroon 5 singer Adam Levine of cheating last week, the internet didn’t exactly overthink the situation. It didn’t spark a wave of earnest discussions about morality on social media, nor did people express the feeling that he (or his wife) had a reasonable expectation of privacy at this difficult time. Worryingly, few even seemed to acknowledge or care that Levine’s wife, Behati Prinsloo, is pregnant and may be experiencing huge trauma right now – simultaneously going viral while carrying the child of someone who’s potentially been telling models “how f***ing hot” they are. No, we processed the challenging life situation of others by... making memes. Hilarious memes recontextualising his vapid and (in Levine’s own words) “flirtatious” messages. We (myself included) turned the awful domestic situation of total strangers into a big in-joke for our own entertainment.

More often than not, we use humour to deflect (or just ignore) the toxic reality of cheating in stories like this. As we’ll see, I think we’ve got here after decades of terrible public dialogues on the subject. But it’s also true we probably deflect it because, when it comes to our own relationships, research indicates we all operate in a state of denial around cheating. As reported by the BBC, though some surveys estimate that up to 75 per cent of men and 68 per cent of women have cheated, apparently only 5 per cent of people think their partner has or will cheat on them. That’s a lot of heads wedged into a lot of sand.

The fact that we spectacularly fail to comprehend cheating in our own lives might be why we don’t take it seriously in others. But I think there’s a specific reason why Brits find it especially hard.

For decades, we’ve let the media take over our moral SatNavs on the subject – feeding us a slew of “sex scandals” that shifted units on the basis that there was a serious significance to the fact that so-and-so might have snogged thingy behind closed doors. If you were alive in the Eighties and Nineties, in particular, you were probably groomed into your confused worldview by a truly terrible man.

Max Clifford was a prolific “kiss and tell” publicist who brokered a slew of sex-cheat headlines. He pushed political ones, like those involving the then Tory culture secretary David Mellor and Labour’s erstwhile deputy prime minister John Prescott, and A-list scandals, such as when David Beckham’s former PA Rebecca Loos claimed they had had an affair – which the former England captain dismissed as absurd.

Yet in a reflection of just how twisted and messed up our national morality is about all this, the man behind these stories was first revealed to be an adulterer and organiser of sex parties, then in 2013 a serious sexual abuser of children as young as seven. He died in 2017.

In the absence of Clifford, coupled with the UK’s tightening of privacy laws after the Leveson Report and the overuse of superinjunctions, a strange thing has happened. Having been a country known the world over for our sex scandals, today we seem to have lost the confidence to discuss cheating in public life. I think we’re in a strange new state of moral confusion: unsure if it’s our business to know about infidelity. Angered and fascinated, but not entirely sure why.

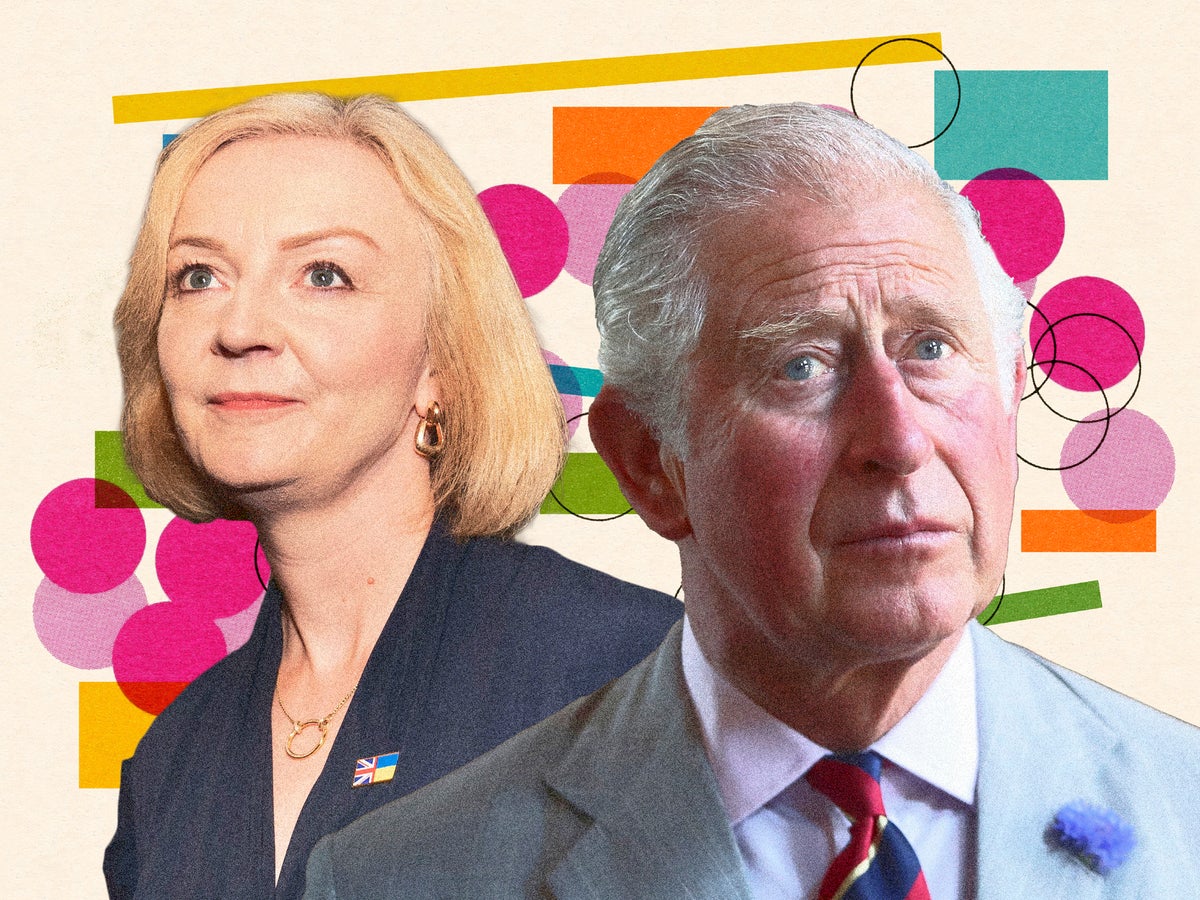

Our new PM, Liz Truss, is the apotheosis of this strange era of “don’t mention the affair”. Did you even know that she’d had an 18-month affair with then Tory MP Mark Field? It began in 2004, four years after she married her husband, accountant Hugh O’Leary, with whom she has two daughters. When she was selected as an MP in 2009, the local party were so incensed over what they perceived as a cover-up about her cheating past that they even voted on whether to deselect her as a candidate. She survived the vote, and the rest is a victory march to glory. Except for Field’s then wife (whose name I’m not mentioning incidentally, lest her Google searches forever be tagged with a trauma from the past). She divorced him in 2006, after 12 years of marriage. She cited his affair with Liz Truss as a factor. I’m sure we all hope she’s doing great today.

While Truss’s local party were up in arms about the affair back then, the present-day Conservative Party seemingly gave zero hoots when they elected her in 2022. Across a painfully long hustings period, the issue of her affair didn’t come up once. There were no questions from journalists, not even think pieces from her ideological opponents on the left. And irrespective of political tribalism, on a very basic human level, nobody asked if someone who keeps an 18-month-long deception is fit for a job that demands probity and propriety. Nobody even wondered if the husband and kids were OK? Are these questions appropriate, or just rude and invasive? Like I say, I don’t think we know any more.

Of course, it helps a politician with a past to have succeeded a man with a past more chequered than a chess board. We don’t need to revisit the many, many alleged indiscretions of Boris Johnson. But the moral chaos of the past few years is begging for some analysis. On the one hand, we have to trust in democracy. Going into the 2019 election, the British people knew full well that Johnson was wayward, hardly first in line for a “#1 Dad Mug” and was probably a bit of a s***. Yet the electorate still backed him hands-down over Jeremy Corbyn. It may seem far-fetched, but I think you could spin the 2019 election as a referendum on morality: conclusive, democratic proof that we don’t expect people in power to have perfect, upstanding and exemplary lives any more.

Yet, on the other hand, is it toxically judgemental and super old-fashioned of me to think that a man of dubious morality was destined to crash and burn in the most important job in the country? That he demonstrably didn’t have the right character to engender respect? Shouldn’t we have taken all that cheating stuff more seriously, instead of treating it like a quirky character trait or a big guffawing joke?

We’re so awkwardly constrained by a sense of moral confusion about affairs that we even try to pretend it’s not happening, even when there’s a PDA graphically staring us in the face. Remember the video of Matt Hancock passionately snogging his aide, his hand... lingering... urgh, sorry, I just can’t. Anyway, despite the unspeakably vivid footage that was being shared, because the media needed to prove a public interest behind running something so salacious, the moral aspect of the story was entirely framed around his sinful breaking of... Covid regulations. For days and weeks afterwards, British people never really talked about the cheating. Not the marriage of 15 years in tatters. Not the mortified family. It was as though nobody could bring themselves to talk about the big, horny elephant in the room.

Nowhere does this sense of tremendous awkwardness exist more than around the new King. When Charles met the young Camilla Shand in 1972, one of the first things she’s reported to have told him was that her great-grandmother had had an affair with Edward VII (Charles’s great-great-grandfather). “I feel we have something in common,” she’s reported to have said. Everybody on earth knows that the new King cheated on his first wife, Diana, and that the Queen Consort cheated on her first husband, Andrew Parker-Bowles. And though the recent solemnities have managed to legitimise the relationship of Charles and Camilla, it was only four months ago that the Queen finally relented to Camilla one day being known as Queen Consort. This marked the end of a very long period of thawing over the previously adulterous nature of her son and heir’s relationship. In 1998, the religiously devoted Queen reportedly wouldn’t even attend a 50th birthday for Charles, just because Camilla was attending. Was the Queen wrong to feel this strongly about adultery?

Looking ahead to the King’s future – in reference to his past – I suspect there may be ups and downs to come. On the plus side, Josh O’Connor, who played Prince Charles in The Crown, is on record as saying that “Tampongate” (the 1993 scandal in which a bugged phone call revealed Charles making explicit remarks to Camilla – after his formal separation from Diana, but before their divorce) won’t be included in the final season of the Netflix show. So that’s something at least. But at the King’s forthcoming coronation, he will have to balance being sacredly anointed as God’s blessed choice to rule us all, whilst trying to live down the fact that he’s already let the boss down by breaking the marriage vows he made in St Paul’s Cathedral in 1981. It’s all just so complicated, isn’t it?

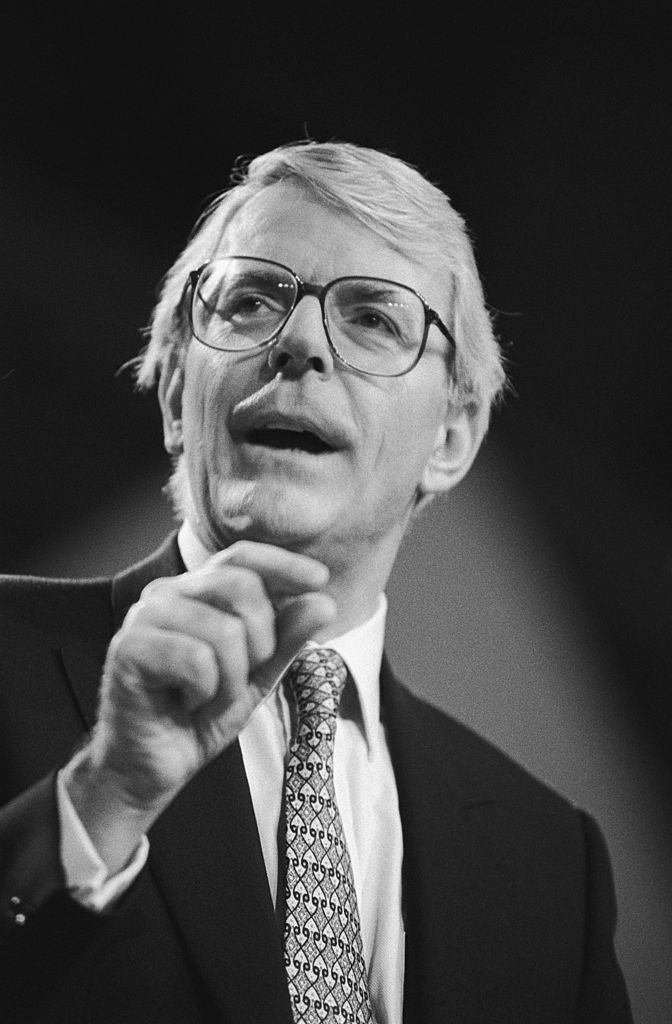

Personally, I really do find the issue of cheating in public life grimly fascinating. Maybe it’s because one of my most vivid (and distressing) memories from childhood was gingerly coming home after a family holiday with terrible food poisoning, opening the door, seeing a newspaper on the matt telling me that John Major had had an affair with Edwina Currie, and wanting to be violently sick. More logically though, it’s experience that’s got me here. Cheating sucks. It absolutely, completely stinks. It’s a way to put sane people on a path to madness. I know this because I’ve cheated, and I know this because I’ve been cheated on. The whole thing is awful.

So even though I should be celebrating a shift away from old-school tabloid coverage of public people’s private lives, I feel like someone is left behind in all this. It’s the cheated-on partner, watching (we presume) with a burning sense of injustice that their cheating-ass ex is able to succeed, to hold power, to elevate themselves, talk about things like tolerance, kindness and decency – all the while carrying the scars of being lied to, being humiliated, of feeling utterly inadequate.

We talk about these things as though monogamy is the rule. It’s not. Alternative relationship structures based around ideas of polyamory and ethical non-monogamy (ie relationships where partners might seek something beyond their established partner or partners, with the informed consent of all concerned) seem more popular than ever before. I think prominent people have a duty to talk about cheating though, why we do it and why it’s so awful. Burying our heads in the sand isn’t good for anyone; neither is hurtling back to an age of deference where the rich, powerful and aristocratic are assumed to be right and never once questioned.

Are the new King and PM unfit for their roles because they’ve been adulterers? No. Is it weird that we haven’t talked about it? Yes, I think so. Would the world be a better place if people – especially those in charge – were honest about everything? Definitely.